Campbell Award & Invisible Disability

Last night I was overjoyed and overwhelmed to receive the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer at the Hugo Awards ceremony at Worldcon 75 here in Helsinki, Finland. I was so overwhelmed by this warmest of possible welcomes to the field that I mounted the stage crying too hard to actually read my speech. I also mounted the stage with difficulty, leaning heavily on my cane. Here is a transcription of the speech I ended up giving, which I want to follow with a few comments. You can see a video of the speech here.

Thank you very much. I have a speech here but I actually can’t see it. I can think of no higher honor than having a welcome like this to this community. This… we all work so hard on other worlds, on creating them, on reading them, and discussing them, and while we do so we’re also working equally hard on this world and making it the best world we possibly can. I have a list with me of people to thank, but I can’t read it. These tears are three quarters joy, but one quarter pain. This speech wasn’t supposed to be about invisible disability, but I’m afraid it really has to be now. I have been living with invisible disability for many years and… and there are very cruel people in the world for which reason I have been for more than ten years not public about this, and I’m terrified to be at this point, but at this point I have to. I also know that there are many many more kind and warm and wonderful people in this world who are part of the team and being excellent people, so, if anyone out there is living with disability or loves someone who has, please never let that make you give up doing what you want or working towards making life more good or making the world a more fabulous place.

I have never discussed my invisible disability in public before, so I want to add a little more detail here for those who must have questions. In my case, the pain comes and goes, often affecting me mildly or not at all, so many of you have seen me singing on stage, or in the classroom, or speaking at a conference with no sign of any pain, but sometimes, as last night, the pain sets in ferociously, too much to hide.

As is often the case with this kind of invisible and intermittent disability, the cause of mine is complicated: for me it’s a combination of Crohn’s Disease (an autoimmune disorder primarily affecting the digestive system), plus P.C.O.S., and some other factors for which I continue to undergo testing. These conditions cause a variety of problems, including inflammation, swelling, and periodic spasms in my lower abdomen. Over the years, this has damaged the muscles of my pelvis. The damaged area can go into spasm at any moment, causing severe pain and difficulty walking, as happened last night. Sometimes the pain is gentle enough that I don’t even notice it. Sometimes it’s medium, so I can walk with a cane and work with effort but get tired easily. Sometimes it is too severe to let me walk or work at all. And once in a while it’s so severe that, without special breathing exercises, I can’t not scream. All medications powerful enough to deal with the stronger forms of the pain also make me extremely sleepy or out-of-it, too much to work, or teach, or give a speech at a Hugo ceremony. So last night, I faced the choice between revealing this to a large public, or turning down the invitation to go receive the honor that means so much to me. So I chose to go to the podium.

As is often the case with this kind of invisible and intermittent disability, the cause of mine is complicated: for me it’s a combination of Crohn’s Disease (an autoimmune disorder primarily affecting the digestive system), plus P.C.O.S., and some other factors for which I continue to undergo testing. These conditions cause a variety of problems, including inflammation, swelling, and periodic spasms in my lower abdomen. Over the years, this has damaged the muscles of my pelvis. The damaged area can go into spasm at any moment, causing severe pain and difficulty walking, as happened last night. Sometimes the pain is gentle enough that I don’t even notice it. Sometimes it’s medium, so I can walk with a cane and work with effort but get tired easily. Sometimes it is too severe to let me walk or work at all. And once in a while it’s so severe that, without special breathing exercises, I can’t not scream. All medications powerful enough to deal with the stronger forms of the pain also make me extremely sleepy or out-of-it, too much to work, or teach, or give a speech at a Hugo ceremony. So last night, I faced the choice between revealing this to a large public, or turning down the invitation to go receive the honor that means so much to me. So I chose to go to the podium.

I had not discussed this in public before because being public about disability (especially for women) so often results in attacks from the uglier sides of the internet, a dangerous extra stress while I’m working hard to manage my symptoms. I have been open about my disability with my students and colleagues at the University of Chicago, every one of whom has been nothing but outstandingly supportive. In fact, much of the strength which helped me get through last night came from the earlier experience of discussing my disability with my students this past year when I had to explain that I might miss class for surgery. Their outpouring of warmth and support was truly beautiful, but I was also awed by how eager they were to discuss the larger issue of invisible disability, and to hear about how I’ve worked to balance my projects and career with my medical realities, a type of challenge which affects so many of us, and many of them. Thinking of their kindness helped me keep my courage up last night, when having an attack at such a public moment made it impossible to avoid having this same conversation in a much more public and therefore scary space.

I was first diagnosed with Crohn’s Disease in 2004, in the third year of my Ph.D. studies at Harvard. My first attack came suddenly, with no warning signs, on the morning I was supposed to have administered the final exam for one of my very first classes. Thanks to good medical care, and careful control of what I eat, the condition went into remission and was mostly dormant for several years, but it took a bad turn in autumn 2012, and another very bad turn in October 2015, which is when the pelvic damage reached its present level. From October 2015 through June 2017, almost half my days were “pain days,” i.e. days I am in too much pain to do anything but lie down. If I’m strong enough to, I usually watch Shakespeare DVDs, my way of at least doing some primary source research on Renaissance history even when I’m too weak to read or type.

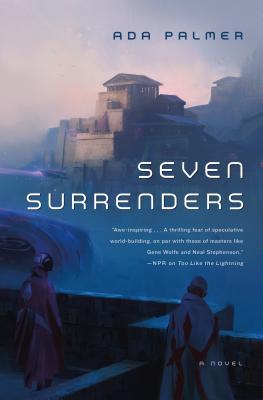

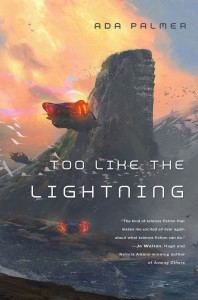

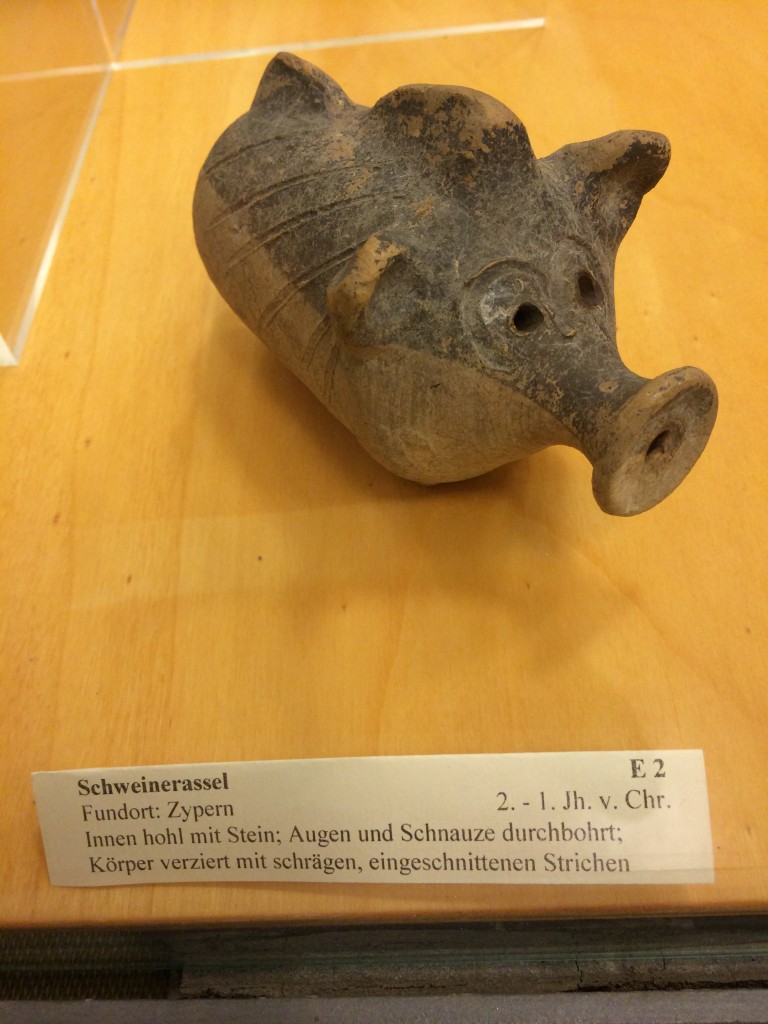

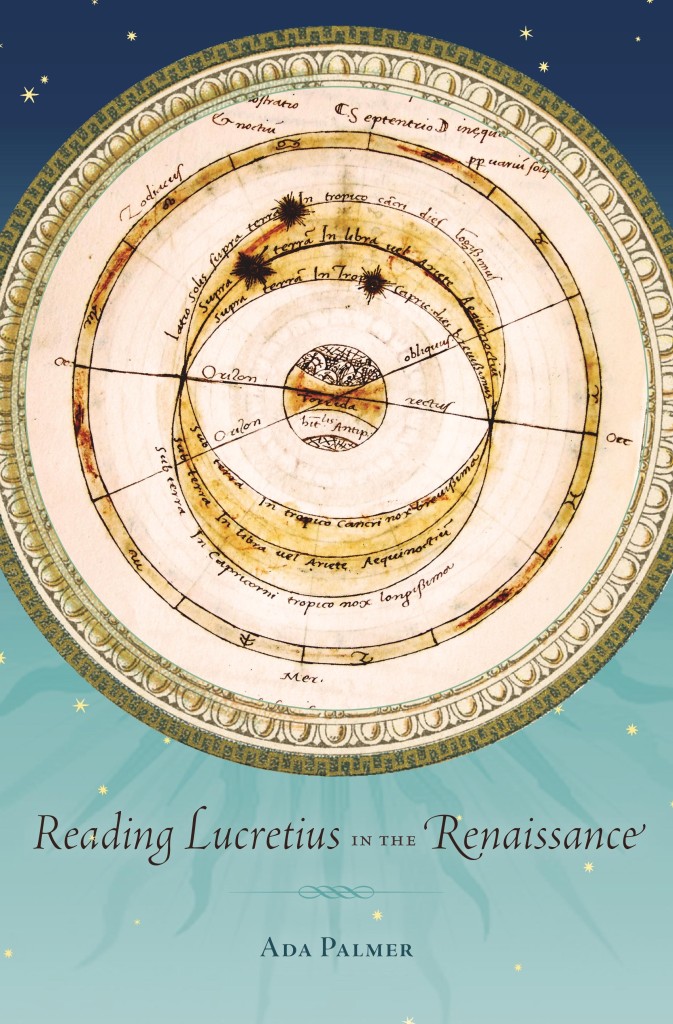

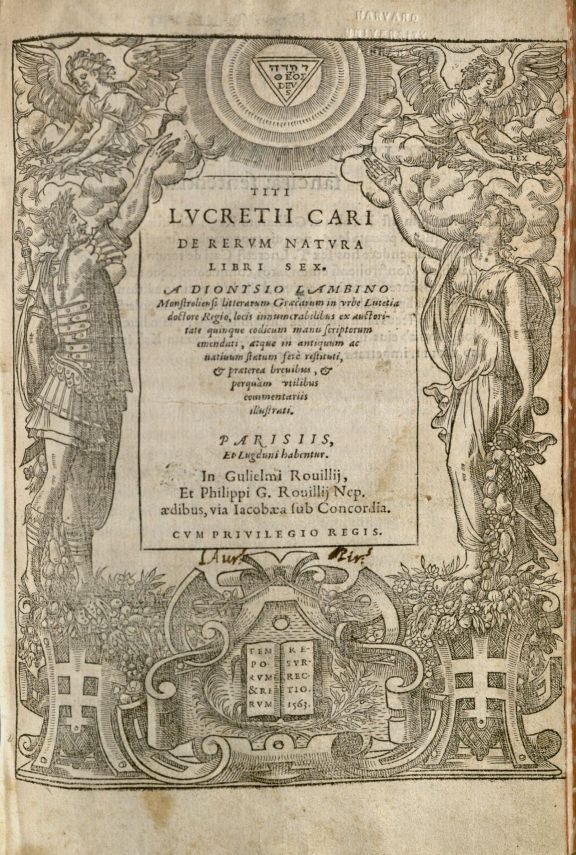

Despite my disability, I have managed, over the past few years, to accomplish many things: publishing award-winning academic articles and my book on Lucretius in the Renaissance, securing a tenure track job at the University of Chicago, composing and recording CDs of my music, and publishing science fiction novels which have now received the warmest welcome to the field I could imagine: the Campbell Award for Best New Writer, the Compton Crook award for best first novel, and finalist for the Hugo Award for Best Novel. But the nasty flare-up that ate so much of 2015-2017 is the real reason that I haven’t posted to this blog much recently, and that the new Sassafrass CD still isn’t done, and that I didn’t do a “blog tour” for the release of my second novel, and that book four Terra Ignota still isn’t done, and that, for the first time, I’ve had to pull out of some academic publications I’d promised to be part of, and turn down invitations that my younger self could never imagine turning down. With more and more opportunities opening before me, one of the hardest parts of living with this disability is learning to say ‘no’ to good and worthwhile things because I need to save those extra days, not for projects, but for pain.

What I have done, what I am doing, I am not doing alone. I have had so many kinds of help from so many people. They were who my speech last night was supposed to be about, because if there is a triumph here, it is the triumph of what can happen when a community of warm, generous people come together. So there was a long list of people I was planning to thank in my speech. I have incredibly supportive parents, Doug and Laura Palmer — thanks to them, I’ve never had to doubt that, when I need help, it will be there. That feeling of safety is invaluable. I also have incredibly supportive housemates Michael Mellas, Lauren Schiller, and Jonathan Sneed, who step up to take care of me when I’m incapacitated, and remind me to take my meds, and often notice before I do when I’m too weak and need to rest, and mean that I never have to push past my limits the way I would if I were alone. I have other friends who’ve helped in so many ways: Carl Engle-Laird, Lila Garrott, Irina Greenman, Jo Walton, and so many more. I have supportive communities: my college science fiction clubs, Double Star at Bryn Mawr and HRSFA at Harvard, my childhood local convention Balticon, and the broader science fiction fan community and filk community. I have the numerous convention staff, liaisons, and friends who have known about my condition for years and been my “spotters” in case I had flare-ups at conventions, and who have kindly honored my request to keep it private. I have colleagues and administrators at my university who instantly rose to the occasion when I brought my condition to their attention, and let me know that if at any time I felt I could no longer handle my teaching duties, they could put things in place to relieve me within 24 hours. I have a team of the best doctors in the world at the University of Chicago Hospitals. (At the risk of making this even more political, I have the larger team who went to bat for America’s health care this year, and preserved the protections without which I could not afford the medications which are finally making my pain days less frequent, and my teaching and writing possible.)

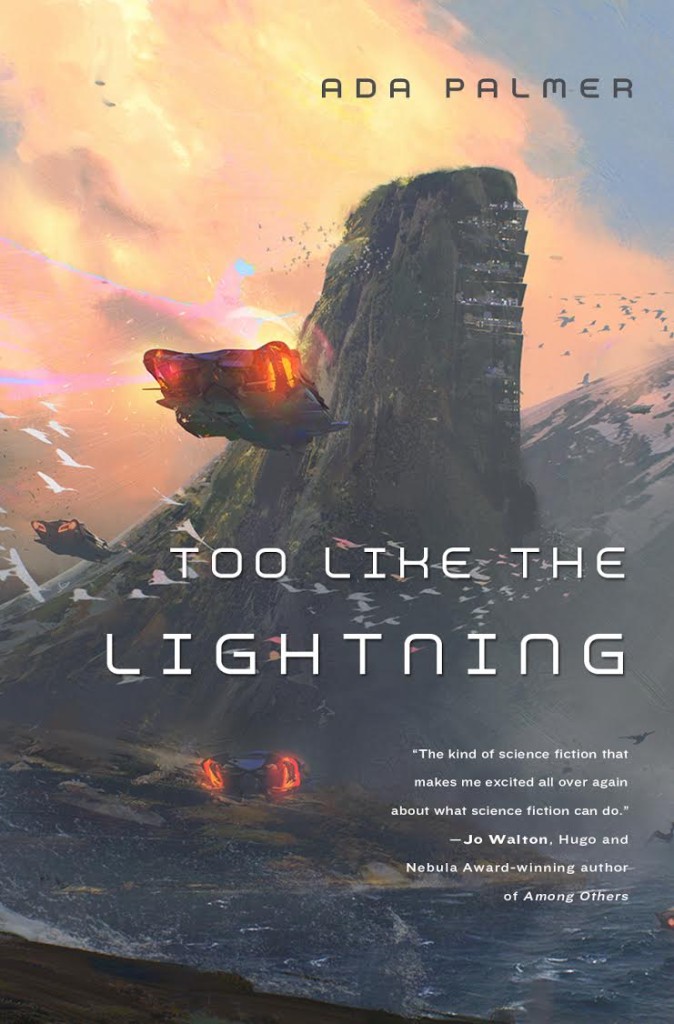

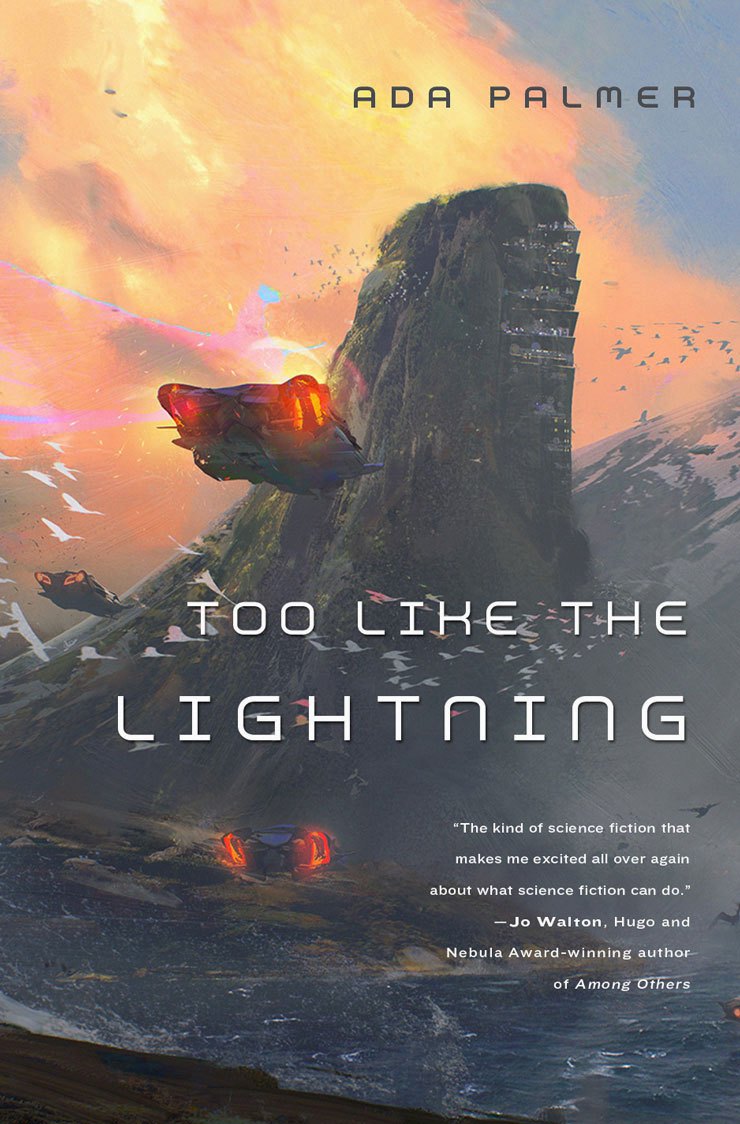

As an author, I’ve had a world class team, too. My agents, Amy Boggs and Cameron McClure, put their all into both disseminating the books and protecting them. My editor, Patrick Nielsen Hayden, always does everything he can to give me the flexibility I need, and his indispensable assistant, Anita Okoye, makes the process run on time. My publicist, Diana Griffin, gets the word out that the book exists, without which it would never reach the readers who are the most important part of all this. My amazing cover artist Victor Mosquera whose covers keep stunning me every time I look at them again. Other friends at Tor and Tor.com help with advice and insights: Miriam Weinberg, Irene Gallo, Teresa Nielsen Hayden. My UK publishing team at Head of Zeus is also fantastic and I can’t wait to do more projects with them.

Nothing means more to me than the opportunity to pay it forward, to build on the immense generosity of everyone who has helped and given me so much, and to give back, through my teaching, my books, my blogging, every conversation, every day. So above all, I want everyone to know that everything I’ve produced, and everything I will produce during my life, living with this condition, is the fruit of the gifts of kindness, large and small, that I have received from so many, many people. Thank you.

Meanwhile I don’t yet have another full essay ready to post here, but I’m happy to say the reason is that I’m working away on the page proofs of

Meanwhile I don’t yet have another full essay ready to post here, but I’m happy to say the reason is that I’m working away on the page proofs of

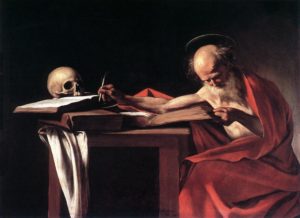

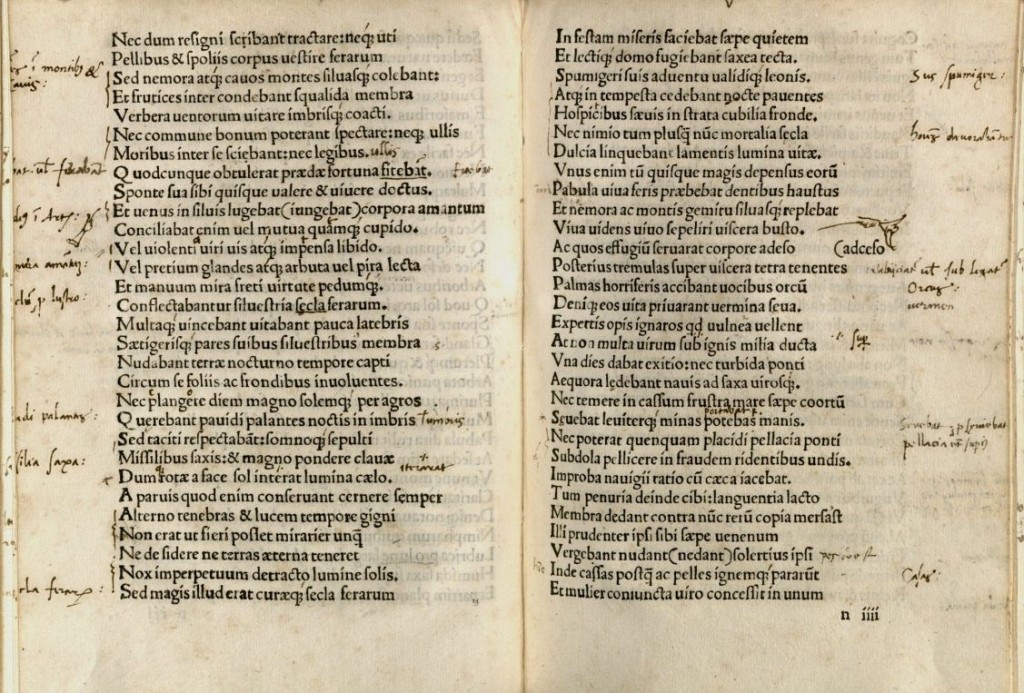

and how that transformed the way people thought about science and religion leading to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. There are many facets to how we got from Dante and Aquinas to Newton and Voltaire, and many people have addressed the question, but usually they look at the leaders and firebrands rather than looking, as I have, at the anonymous reading public where the deeper mass transformation had to happen for ideas which were once radical heresies to become comfortable parts of daily life. To put it another way, if you read or heard about Stephen Greenblatt’s book

and how that transformed the way people thought about science and religion leading to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. There are many facets to how we got from Dante and Aquinas to Newton and Voltaire, and many people have addressed the question, but usually they look at the leaders and firebrands rather than looking, as I have, at the anonymous reading public where the deeper mass transformation had to happen for ideas which were once radical heresies to become comfortable parts of daily life. To put it another way, if you read or heard about Stephen Greenblatt’s book