The Key to the Kingdom, or How I Sold Too Like the Lightning

I want to share an essay today, one of the most personal things I’ve ever written, and one of those I’m proudest of. It’s about how I sold my first novel.

I want to share an essay today, one of the most personal things I’ve ever written, and one of those I’m proudest of. It’s about how I sold my first novel.

I’ve been stunned since I learned Too Like the Lightning is a finalist for the Best Novel Hugo. This really is the highest honor I can imagine, my work being recognized as one of the most valuable contributions to the community of conversation which drives us forward through speculation about other worlds to touching and creating them, both here on Earth and out among the stars. The community where the Great Conversation thrives. While I always intended to contribute to that conversation, I never expected this kind of reception for a very difficult and intentionally uncomfortable book, one which I had imagined as finding an excited but niche audience, never a large one. I haven’t known what to say other than “Thank you!” but a common “Thank you!” feels mismatched, like paying the same 50¢ at a rock shop for a shiny hematite one week and the Philosopher’s Stone the next. And I’ve also been swamped with final exams, colliding deadlines, three European conferences, research travel, illness, editing book 3, preparing a new project on the History of Censorship (more on that later), all the usual time-eating co-conspirators that make it easy to put off anything difficult. And it is difficult to figure out how to write a world-sized thank-you to match this world-sized joy.

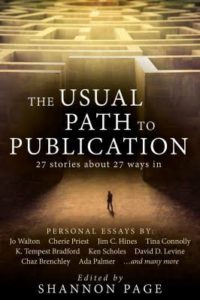

But I think one appropriate thank-you is to share this essay. I wrote it for Shannon Page for her brilliant collection The Usual Path to Publication (Book View Café, 2016), which contains 27 different authors’ stories about how we sold our first novels. The volume’s variety succeeds in showing what it set out to, that there is no “usual path,” no consistent method, no one piece of advice that always helps on the path that no two people ever walk the same way. The book is absolutely my top recommendation for new or aspiring writers (also this really really good Book Riot Article on how much money authors make incl. self pub & traditional pub).

I suspect I’m not the only contributor to The Usual Path to Publication who found that the story that came out, when I tried to tell it, was so personal, so saturated with the most intense emotion, that I was more than a little nervous sharing it at first. But I also think telling the story means even more now that it has a Hugo nomination at the end of it, and a Campbell nomination, and the Tiptree Honors List, and the Compton Crook Award. Because I grew up in Maryland, so I’ve seen the Compton Crook Award given out to a Best First Novel in the genre every year at since I was a little girl, every time thinking “Maybe someday it will be me?” So this is how I got to Someday.

The Key to the Kingdom, or, How I Sold Too Like the Lightning.

by Ada Palmer, 2016

Some people say revenge is living well –

I’ve found it sometimes works to go away

And be more awesome. Let him sit alone,

To watch your wildfires leaping as you play.-Jo Walton, “Advice to Loki” 2013.

The midpoint first, then the primordial darkness, then the ever after.

It was 2011 (remember, this is the creation myth of a book that won’t come out until 2016). I was in Florence, sitting in the top of a 13th century tower between Dante’s house and my favorite gelato place (extra relevant in an un-air-conditioned August!), and talking to Jo Walton about whether or not I should start a blog. It was the beginning of a year in Florence, a postdoctoral research fellowship at the Villa I Tatti, Harvard’s institute for Italian Renaissance studies. Life as a Renaissance historian had granted me long stays in Florence twice before, once on a student Fulbright, and once taking a shift as I Tatti’s resident grad student mascot (#1 duty, be introduced to rich donors and look bright-eyed and promising). During my earlier stays I had written a series of e-mails describing my Italian experiences, and sent them to a list of friends and family. The list grew over time as the recipients recommended them to more distant cousins and acquaintances, until I had nearly a hundred people on my list. In fact, those e-mails were how I knew Jo. One of my then-roommates, Lila Garrott (a poet, author, book reviewer, and now editor at Strange Horizons) had posted a few of what, in neoclassical style, I called my “Ex Urbe” e-mails on LiveJournal, where Jo had enjoyed them. In 2008 Jo had invited Lila and the rest of our eclectic household to visit her for Farthing Party in Montreal. Jo was with me in Italy that August because the question “Do you want to come stay in my apartment in a 13th century tower in Florence?” has one correct answer. “I wonder if it would be less work to just post them on a blog,” I said, overwhelmed by trying to assemble the new list of people who had asked to receive my e-mails. Jo looked at me very seriously. “If you make a blog, I’ll send the link to Patrick Nielsen Hayden.”

I did make a blog. (This blog.)

In three months, it was in the sidebar of Making Light.

In six months, Patrick asked Jo if the author of this ExUrbe blog had written any fiction.

In two years (almost to the day, August 2013) Patrick bought Too Like the Lightning.

My appetite to see my fiction in print had been overwhelming since elementary school, and I vividly remember the thrill of standing on tiptoe to watch my first typed story (a single paragraph, about blue-and-silver alien raccoons) crawl its way out of the astounding new dot matrix printer at Dad’s office. I had begun a novel by fourth grade, three by tenth, and I devoured summer writing courses, of which the courses on essay writing (Johns Hopkins) and prose poetry (Interlochen) proved far more valuable than the fiction ones. I remember once thinking to myself at fifteen, bored during a school convocation, that if I hadn’t published a novel by twenty-five then… the end is vague. Then I should give up? Then I was a failure? Then I should curse the heavens? It was my first serious college writing mentor Hal Holiday who helped me understand how absurd that was. He made me cry in his office, with my first-ever B on a paper. I didn’t understand what I’d done wrong. “Writing is a long apprenticeship,” he said. I hadn’t done anything wrong, but writing well—not well for your age group, but well in an absolute sense—was hard to achieve. It took real time. Spending every childhood summer and weekend writing, taking every summer writing course, those were good steps, they helped, but they were a beginning. I finished my first novel draft that year, flipped back to page one, and started writing it all over again.

In 2002, at twenty-one and with Mom to stuff the envelopes, I sent my (totally-rewritten) first novel-length manuscript winging its optimistic way to slush piles at agencies and publishers. I sometimes think, if we could harvest the emotional energy in all the fat manila query envelopes aspiring writers entrust to the post office every day, we could move planets. I have a folder of rejection letters from that first volley, and, looking over them now, I can see the good signs in them, the peppering of personalized notes, praise and encouragement among the form letters. I didn’t understand then how many queries editors, agents and interns read, how generous it was for them to sacrifice precious seconds to write these extra lines (thank you!), but it did a lot to keep me going. And in the back of the folder I always kept a printout of Ursula Le Guin sharing a very grim rejection letter she received for The Left Hand of Darkness, with her note “This is included to cheer up anybody who just got a rejection letter. Hang in there!” Thank you. After eight months of agonizing suspense, and the sporadic gut-punch of rejections, that first volley got me an agent. She was not an F&SF specialist, but was game to try, and spent the next years doggedly marketing what neither of us realized was an unsaleably long fantasy novel.

I don’t remember where I received the wisdom that it’s better to go on and write Book 1 of a new series rather than write Book 2 of a series when you haven’t sold Book 1 yet. Wherever I got it from, I obeyed it, and soon my plucky agent was shopping two series, then three. Despite loving to sleep in, I followed the old advice and wrote in the morning, every day, an hour or two, giving my best hours to fiction and the rest of the day to the demands of grad school, and thereby wrote close to a million words of fiction over seven years. Looking over those practice projects now, I can see my writing improve with each, the sentences, the pace, the plot. Every paragraph was a step in that long apprenticeship. The wait stretched on—three years, four—and it hurt—the growing, gnawing appetite. Sometimes I would lie awake at night just from the pain of wanting something so much. But I had an agent, and that gave me confidence, and comfort.

Meanwhile I was working on my Ph.D. The single best thing that ever happened to my writing—looking at the novel I was working on at the time you can see the very chapter break where it happened, like lightning struck and *ZAP!* the prose was finally good—was in 2005, when I had to cut down my 20,000 word dissertation prospectus into a 7,000 word conference paper. Without knowing it, I had stumbled on “Half and Half Again,” as it’s called by people I know in journalism, a training exercise in which you go through the agony of cutting an old work down to half length, then half of that, learning to spot the chaff and bloat in your own work, and how to make it tight and powerful. Lightning. I published other things—my first academic article, blog pieces for Tokyopop about manga & cosplay, a Random Superpower Generator for Maple Leaf Games, but none of them eased the wanting. I also learned more about the world of genre publishing, from going to conventions and chatting with author friends made through Lila, and through my science fiction clubs, HRSFA (the Harvard-Radcliffe Science Fiction Society), and Double Star (at Bryn Mawr College). F&SF specialist agent Donald Maass spoke to us at Vericon, a great little con HRSFA runs at Harvard every year, and I learned from his talk about the field, the extreme oversupply of submissions, the challenges of length and salability. I had queried Donald Maass (unsuccessfully) way back in 2002, but in 2006, with my writing much improved, preparing to begin a new series which I felt in my gut was leap above the others (and eventually became the Terra Ignota series), I decided to break off my relationship with my first agent (with much gratitude and good will) and to try fresh to get a new agent at a major F&SF specialist agency.

I finished the first draft of Too Like the Lightning (Book 1 of Terra Ignota) in 2008, my penultimate year of graduate school. Between 2002 and 2008, plump manila envelopes had evolved into instantaneous e-queries, and my generic cover letters had acquired the varnish of name-dropping. I had recommendations from random people in the publishing world (Walter Isaacson, Priscilla Painton) whom I had met through Harvard. And, while my first 2002 volley had showered queries on dozens of doorsteps (many quite inappropriate), I sent Too Like the Lightning to only one press in 2008, my great hope: Tor. The more I learned about the world of genre publishing, the clearer it became that Tor was one of the only (if not the only) press that had the stability and resources to gamble on a big, fat science fiction series (four long books!) by a first time author, books which were dense and highbrow, and totally not similar to anything—trends are a safe investment; oddities are a gamble. Plus, I had an ‘in’. There were people at Tor who were friends of friends, alumni and associates of both Bryn Mawr and Harvard, some of whom knew my Double Star and HRSFA connections. (Yes, I tried nepotism for all it was worth, anyone would—I still lay awake at nights, just wanting.)

After another year of lying awake and wanting (and finishing my Ph.D., and facing the academic job market, which in 2009 had just entered its sudden death spiral), a Tor contact told me (I think at Readercon?) that the book had advanced from the “slush” pile to the “shows promise” pile. This was good news, but an un-agented manuscript, which the editor knows has been sent to no other press, can stew in that pile forever. That November I queried Donald Maass, hoping a kind word from Tor would help me get an agent, and that a good agent might prod along the literary glacier. I even got a Harvard-made mainstream publishing contact to e-mail Donald Maass with his endorsement to accompany my query. (Roll for nepotism! Did it achieve anything? Not really!) On December 31st, I received an e-mail from Donald apologizing for losing my query and getting back to me so late (apologizing for a delay of only 2 months! Such professionalism! Such sanity!) and saying he loved the beginning of the book, and was eager to read the whole thing. I sent it right away. I waited. I shopped other, older projects with a YA agent recommended by a friend (no luck). I published other things—more academic articles, critical essays, introductions to manga and anime releases. I stayed up nights. Sometimes it was so bad I couldn’t go into a bookstore without feeling sick to my stomach. In November 2010 (a full year after Donald had asked for the book) Amy Boggs, then a fairly new member of the Donald Maass Agency, wrote to say that Donald—swamped by unspecified and mysterious stuff—had passed the book on to her, and she loved it. We finalized the contract by early December, and Amy started shopping the book around in the beginning of 2011.

That spring I received my I Tatti Fellowship, and that summer I sat in a tower in Florence with Jo Walton, contemplating a blog. Jo had talked to me about Patrick Nielsen Hayden, though I also knew of him from other sources; legends of such titans echo far through our little magic kingdom.

There is a fresco by Perugino in the Sistine Chapel, which shows St. Peter, in a beautiful neoclassical square, receiving the Keys to Heaven from Christ, with a group of apostles and others gathered around to watch. It’s a deeply tender moment, Peter’s awe at the sight of the divinity which is also the friend he loves so much. But I can never see it without imagining the next panel of the comic book, where Christ has gone back to Heaven, and Peter is left in the square holding these enormous gold and silver keys, and everyone is standing around awkwardly, trying not to stare, and someone sidles up saying, “So… can I get you a cup of coffee?” You can’t put them down, that’s the thing, once you have the keys to Heaven, no one on Earth can forget it, not for an instant. And that’s very much what it’s like being an acquiring editor (I’ve described this to Patrick, he agrees), because you have the Keys to the Kingdom, and people around you—at conventions, at talks, online—want it so much. So much they lie awake at night. There are infinite horror stories about editors being harassed and chased at cons, having manuscripts shoved under bathroom stall doors, repeated e-mails which get weirder and more desperate. So, from childhood (picture me scrawny and eleven, following Dad and Uncle Bill to a Doctor Who convention, with my boy-short bright blonde hair, dressed as the Peter Davison Doctor) I had it drilled into me that you should never approach and bother an editor (or published author) about your manuscript. Q&A when they were on panels was OK, but outside that sphere verboten! In fact, I had met Patrick at Farthing Party back in 2008, but, knowing who he was, I was an emotional wreck just being near him, racked between the Scylla of my desire and the Charybdis of the taboo, so I spent much of the weekend actively hiding around corners and behind pillars to avoid looking at him. But Jo knew I had a manuscript, and passed it on to Patrick for me in spring of 2012 when he asked her if the author of ExUrbe had written any fiction.

And I waited. And I lay awake at night. On a trip to New Orleans, an editor friend of Jo’s told a story about a query which had taken twelve years to be accepted, which actually made me throw up. I tried to start another novel series, but I couldn’t. Terra Ignota meant too much to me, so I broke my own law and wrote Book 2. And Book 3. So many heartfelt eggs in that basket. Amy had occasional non-news for me, and I was overseeing the publication of my first nonfiction book, the academic history Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance, which will hopefully (knock all the wood you can!) get me tenure here at the magnificent I-dare-you-to-prove-it’s-not-Hogwarts University of Chicago. (Where I teach history of magic. Really.) [addendum 2018: I got tenure!!] I had submitted the monograph proposal to Harvard University Press way back in 2009. Given the infamous snail’s pace of academic publishing, I often thought of Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance and Too Like the Lightning as twins fighting to see which would be the first to make it out. But Tor, wonderful, infuriating, experimental, ambitious, field-shaping Tor, is slower.

In March 2013, Jo reported to me that Patrick had said positive things to her about the first page of Too Like the Lightning. One page down, 333 to go. That spring and summer were the madness of producing and recording my two hour close harmony a cappella Viking stage musical Sundown: Whispers of Ragnarok, and its demands were exhaustion enough to let me mostly sleep. As August came along, Patrick told Jo to tell me (in our surrealist game of telephone) that he and Teresa wanted to have dinner with me at Worldcon in San Antonio, and I should have my answer then. This was more than a year after Patrick had asked for the manuscript, and five years after I had first submitted it to Tor.

I was working a booth at that Worldcon, an outreach display for the Texas A&M University Cushing Memorial Library and Archives, which has one of the world’s great science fiction collections, an impregnable treasure vault full of rare pulps, fanzines, first editions, and the archived papers of authors from Star Trek scriptwriters, to George R.R. Martin, to (now) me. (Are you a writer? Do you have random papers and notes from old projects cluttering your house? Cushing’s awesome librarians totally want to take your clutter, index it, and preserve it for posterity! Win-win!). The first morning of Worldcon, I was walking through the dealer’s room on my way to our booth, when Jo Walton gestured me over to the table where she was doing a signing. I gestured back that I didn’t want to interrupt the people who were waiting patiently in line, but she flailed emphatically, so I came. She told me that Patrick told her to tell me “Yes.” I remember hugging, and crying, and intense crying, and gasping out a vague apology to the guy who was in the front of the line, but he said “It’s OK, it’s clearly important.” Jo smiled at him and said, “She’s just sold her first novel!” A keen, satisfied, brightness entered his face, like when you taste an unexpectedly excellent sour candy, and he said, “So, it does happen.”

Most of the rest of the San Antonio Worldcon is lost in the mists of bliss amnesia. I remember staggering back to the Cushing booth all puffy and red-faced, and struggling to communicate to my colleague Todd Samuelson that I was OK, just overhappy from yes! Yes! YES! I remember I couldn’t find my phone to text my dear friend Carl Engle-Laird (a HRSFA alum, who was then a new editorial assistant Tor.com, and sharing my suspense) so I borrowed a phone from Lauren Schiller (my singing partner and roommate of 10+ years), only I couldn’t see through my tears, so the message came out all garbled and full of typos and r5and0m nuMB4rs. I was on a panel right after that, with Lila Garrott (whose online connections had been so instrumental in all this), and I had no time to break the news before the panel, so I just typed it on my then-recovered cell phone and set it on the table in front of us: “Patrick said yes.” Lila glowed.

After Jo’s signing, we found Patrick in the concessions area, and there ensued perhaps the most absurd conversation I shall ever have. I was still paralyzed by the aftereffects of Scylla and Charybdis, so shy and overwhelmed that I could barely force myself to look directly at the legendary Patrick. But Patrick is himself a naturally shy person, and skittish after so many years carrying the Keys to Heaven, so he couldn’t look at me either. And there we were, both trying to hide behind Jo (who is a head shorter than both of us), unable to make eye contact while trying to talk about how we wanted to work together for the rest of our careers. That was when I started to see the absurd flip side of it: all the while that I had been terrified of approaching this incredibly important editor who had power over everything I ever wanted, in his world I had been the intimidating one, this distant Harvard Ph.D., with all these impressive publications, this learned and authoritative tone on my blog, and I had everything he wanted, great science fiction that it would be a pleasure to publish. In Settlers of Catan terms, I had bricks, he had wood, but we were so mutually overwhelmed neither of us could get the words out: “Shall we make this road?” We had dinner with Jo and Teresa at one of those Brazilian Barbeque places, where they hunt the great beasts of the plains and serve them to you on spits carried by excessively statuesque young men—at least that’s what Jo says, because bliss amnesia has erased everything except a vague memory of asparagus and a beige tablecloth. I remember Patrick said he and Teresa wanted to audition to edit and shape my career. Audition? I would have begged!

Patrick took me to the Tor party that weekend. I know he introduced me to Tom Doherty and fifty other genre VIPs, but I genuinely don’t remember a thing except recognizing Liz Gorinsky from a distance by her hair. Patrick forgot to give me his business card, so I almost left without the ability to contact him. It took three weeks to stop feeling like a dream. No, that’s not true—it still feels like a dream. I signed the four book contract by crackling firelight, huddling over the hearthstone during the power outage caused by a New Year’s blizzard, which absolutely feels like a dream. I have a release date now (that took two years), and cover art (same), and the Advanced Bound Manuscript in front of me (well, a defective ABM missing the last three chapters—oops!), and I have a fantastic recording of Patrick—the Patrick—playing guitar with me while I sing my ode to fandom’s support of space exploration “Somebody Will” (super ultra win condition!). But I still feel prepared to wake up tomorrow, back in my old bedroom, and discover it was all a dream. Maybe there will always be that edge of doubt, the scar of how intensely I worried that the door might never open. Sometimes it doesn’t. But if it did open for me, it wasn’t because I kept pounding on the gate with the same desperate query. And it wasn’t the favor-trading, or the Harvard connections, or my attempts at nepotism, or even (honestly) my agent (though she’s done so many great things for me then and since). It was that I set forth to be more awesome. I kept honing my craft, starting new projects better than the last, producing other works, articles, music, essays, research, the blog. I made my fire burn bright in the dark. People do see.