News: University of Chicago, Lucretius Book, Train Tour

I have news to share, though not yet a new post in my Skepticism series, so thank you for your patience on that. I will have a post up tomorrow, though, on a different topic. But for now, news:

I have news to share, though not yet a new post in my Skepticism series, so thank you for your patience on that. I will have a post up tomorrow, though, on a different topic. But for now, news:

First, I’m leaving Texas and starting this fall in a new position as an Assistant Professor in the History Department of the University of Chicago! I’m positively giddy. The university and department are so excellent, and when I visited campus the student conversations I overheard were about Marx and Hegel instead of football, and Chicago is a grand metropolis filled with libraries and museums and architecture and food, and I’ll have grad students! Real grad students! So, in the academic sense, as my dissertation advisor said when he heard the news, “now there will be grandchildren.” Anyone with thoughts or advice on moving to Chicago, please share them!

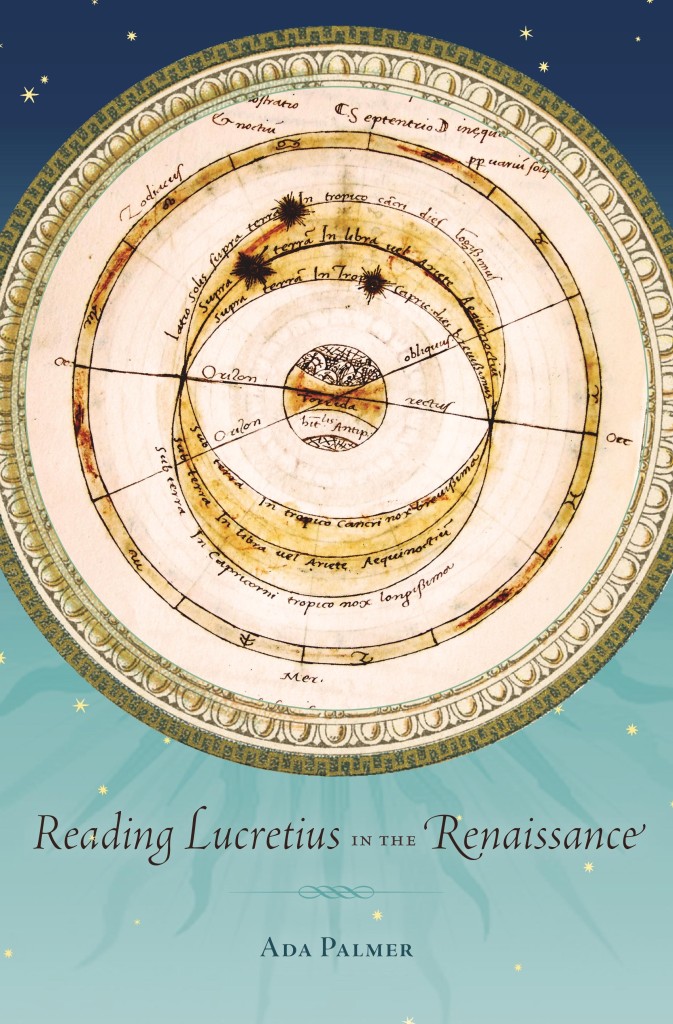

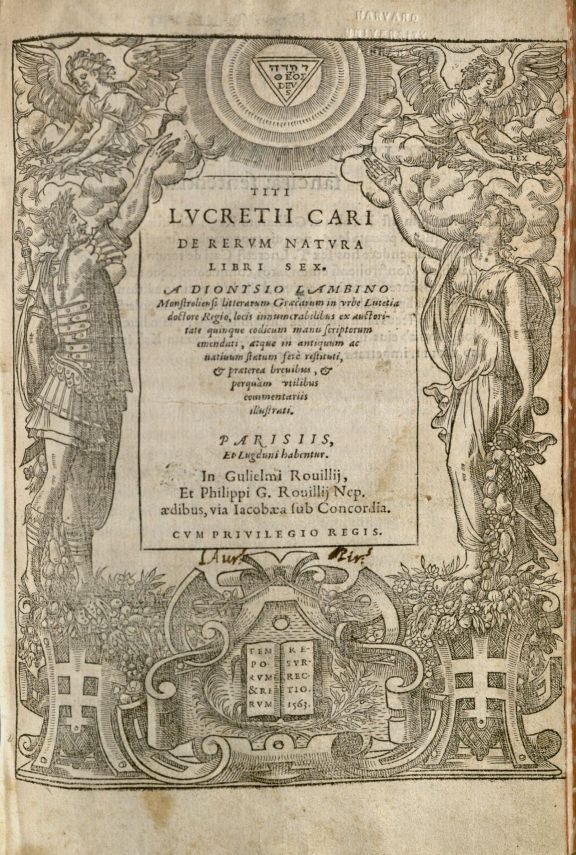

Second, my academic book is now up for pre-order on Amazon. And it has a gorgeous cover! (And relevant, since the diagram is from one of my manuscripts.) It’s also on Harvard University Press’s page, where the money goes to the press, but they (A) don’t have a pre-order option and make you wait until September, and (B) charge $9 more than Amazon, so I understand many of those who want the book will prefer the easy, instant purchase to the inconvenient, expensive one even if the latter helps the press.

Here’s the write-up from the publisher:

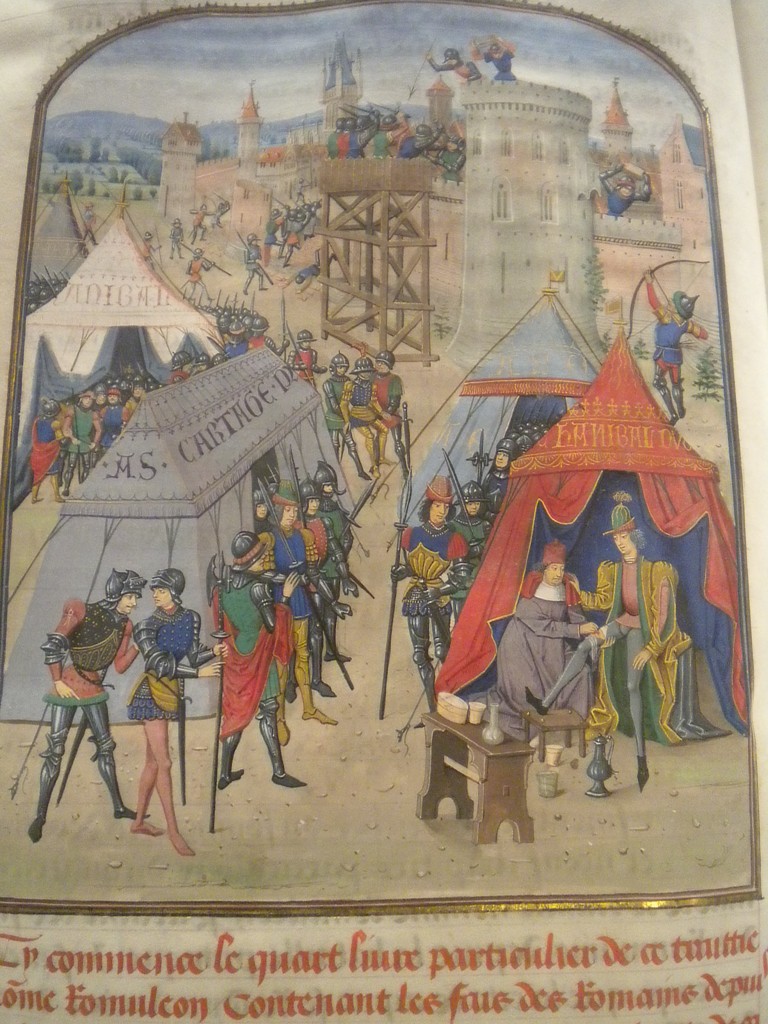

After its rediscovery in 1417, Lucretius’s Epicurean didactic poem De Rerum Natura threatened to supply radicals and atheists with the one weapon unbelief had lacked in the Middle Ages: good answers. Scholars could now challenge Christian patterns of thought by employing the theory of atomistic physics, a sophisticated system that explained natural phenomena without appeal to divine participation, and argued powerfully against the immortality of the soul, the afterlife, and a creator God.

Ada Palmer explores how Renaissance readers, such as Machiavelli, Pomponio Leto, and Montaigne, actually ingested and disseminated Lucretius, and the ways in which this process of reading transformed modern thought. She uncovers humanist methods for reconciling Christian and pagan philosophy, and shows how ideas of emergent order and natural selection, so critical to our current thinking, became embedded in Europe’s intellectual landscape before the seventeenth century. This heterodoxy circulated in the premodern world, not on the conspicuous stage of heresy trials and public debates, but in the classrooms, libraries, studies, and bookshops where quiet scholars met the ideas that would soon transform the world. Renaissance readers—poets and philologists rather than scientists—were moved by their love of classical literature to rescue Lucretius and his atomism, thereby injecting his theories back into scientific discourse.

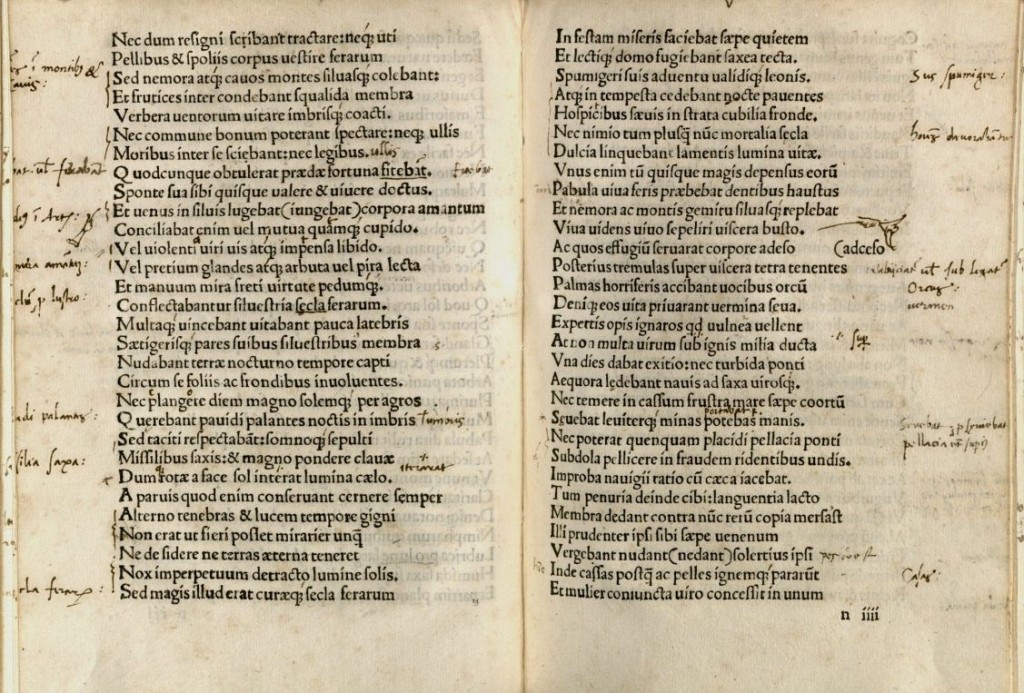

Palmer employs a new quantitative method for analyzing marginalia in manuscripts and printed books, exposing how changes in scholarly reading practices over the course of the sixteenth century gradually expanded Europe’s receptivity to radical science, setting the stage for the scientific revolution.

“This is a brilliant scholarly work that is deeply relevant to today. In exploring the influence of Lucretius on the Renaissance, Ada Palmer shows how the modern world became open to the ramifications of mechanical science. More broadly, her book is a fascinating look at how ideas ripple and spread.” —Walter Isaacson

I promised to be direct and honest when I talked about this book here. This is not a lite, lively fun history like the essays I post on Ex Urbe. It’s a formal academic history. Ex Urbe readers will find that the beginning and the end are in the familiar, strong-strokes voice you’re used to (I moved myself to tears last night doing the page proofs of the Conclusion, a good sign at a stage when one is usually so sick of the manuscript as to be exhausted by the sight of it!) but the middle is meticulous and detailed, and unavoidably a bit dry. It has to be. It’s new data, and new data has to be presented in full, with charts and lists and all that opposite-of-jazz. I’m taking on a big question: how we got from the alien mindscape of the Medieval world to the familiar modern one, specifically looking at how we evaluate true and false, and how we use science and religion in our daily lives. I can’t say something new about that without justifying it with facts and endnotes. This is the fruit of my years of research on manuscripts and marginalia, and I use my results to build up a portrait of how exactly thinking, scholarship and above all reading changed between 1400 and 1600

I promised to be direct and honest when I talked about this book here. This is not a lite, lively fun history like the essays I post on Ex Urbe. It’s a formal academic history. Ex Urbe readers will find that the beginning and the end are in the familiar, strong-strokes voice you’re used to (I moved myself to tears last night doing the page proofs of the Conclusion, a good sign at a stage when one is usually so sick of the manuscript as to be exhausted by the sight of it!) but the middle is meticulous and detailed, and unavoidably a bit dry. It has to be. It’s new data, and new data has to be presented in full, with charts and lists and all that opposite-of-jazz. I’m taking on a big question: how we got from the alien mindscape of the Medieval world to the familiar modern one, specifically looking at how we evaluate true and false, and how we use science and religion in our daily lives. I can’t say something new about that without justifying it with facts and endnotes. This is the fruit of my years of research on manuscripts and marginalia, and I use my results to build up a portrait of how exactly thinking, scholarship and above all reading changed between 1400 and 1600  and how that transformed the way people thought about science and religion leading to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. There are many facets to how we got from Dante and Aquinas to Newton and Voltaire, and many people have addressed the question, but usually they look at the leaders and firebrands rather than looking, as I have, at the anonymous reading public where the deeper mass transformation had to happen for ideas which were once radical heresies to become comfortable parts of daily life. To put it another way, if you read or heard about Stephen Greenblatt’s book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (which won the Pulitzer in 2012 and which I am proud to say I helped with a little bit) it treats the same topic, the rediscovery of Lucretius which suddenly gave Europe access to radical materialism, but The Swerve is about the thrill of the discovery, not its context, cause or mechanism. As I say in my own introduction: “Previous studies have described the epicenter or the ripples–I shall endeavor to describe the medium that carried the ripples so far.”

and how that transformed the way people thought about science and religion leading to the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. There are many facets to how we got from Dante and Aquinas to Newton and Voltaire, and many people have addressed the question, but usually they look at the leaders and firebrands rather than looking, as I have, at the anonymous reading public where the deeper mass transformation had to happen for ideas which were once radical heresies to become comfortable parts of daily life. To put it another way, if you read or heard about Stephen Greenblatt’s book The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (which won the Pulitzer in 2012 and which I am proud to say I helped with a little bit) it treats the same topic, the rediscovery of Lucretius which suddenly gave Europe access to radical materialism, but The Swerve is about the thrill of the discovery, not its context, cause or mechanism. As I say in my own introduction: “Previous studies have described the epicenter or the ripples–I shall endeavor to describe the medium that carried the ripples so far.”

So, that’s my first academic book. If it sounds exciting to you, it’ll be out in September-ish 2014 through Amazon or HUP, or your preferred library or other book source. And if you’re a bookstore person here’s the flier with the special bookstore info. If it sounds like it’s not your thing, no worries: 2015 will bring the novels, and the fun stuff on Ex Urbe will continue to flow.

My third piece of news is that, at the end of this May, I’m embarking on a train tour of major cities of the USA, accompanying my good friend and fellow Tor novelist Jo Walton as she tours with her new novel My Real Children (a 20th century alternate history story about life, small choices, and gelato, that makes everybody cry.) Starting at Balticon and culminating with Readercon and then Worldcon in London, it’ll be an exciting hop through many cities as I meet librarians and bookstore owners, plus Jo and I have a quest to eat great food with awesome people as many times as possible. And on June 22nd, when Jo does her reading in the Jean Cocteau Cinema in Santa Fe (an excellent independent venue owned by George R. R. Martin), I will do a concert of my music (some Viking some not) joined by my duet partner Lauren Schiller, performing as the duo “Sassafrass: Trickster and King.”

My third piece of news is that, at the end of this May, I’m embarking on a train tour of major cities of the USA, accompanying my good friend and fellow Tor novelist Jo Walton as she tours with her new novel My Real Children (a 20th century alternate history story about life, small choices, and gelato, that makes everybody cry.) Starting at Balticon and culminating with Readercon and then Worldcon in London, it’ll be an exciting hop through many cities as I meet librarians and bookstore owners, plus Jo and I have a quest to eat great food with awesome people as many times as possible. And on June 22nd, when Jo does her reading in the Jean Cocteau Cinema in Santa Fe (an excellent independent venue owned by George R. R. Martin), I will do a concert of my music (some Viking some not) joined by my duet partner Lauren Schiller, performing as the duo “Sassafrass: Trickster and King.”

If any Ex Urbe reader (or Sassafrass friend) would like to come to one of the readings and say hello, please let me know in the comments here.

- 23-26th May, Balticon, Baltimore

- 27th May, 7pm, The Word, Brooklyn

- 28th May, 7pm, Wellesley Books, Boston

- 29th May, afternoon, BEA, New York

- 1st June, 3pm, Skokie Library, Chicago

- 3rd June, 5pm, Uncle Hugo’s Minneapolis

- 7th June, 4pm, University Bookstore, Seattle

- 9th June, 7pm, Powells, Portland

- 13th June, 7pm, Copperfields, Petaluma, San Francisco

- 14th June, 3pm, Borderlands, San Francisco

- 17th June, 7pm, Mysterious Galaxy, San Diego

- 21st June, 3pm, Page One Books, Albuquerque, followed by dinner with local SF group

- 22nd June, 7pm Jean Cocteau Cinema, Santa Fe, with Sassafrass: Trickster and King <= me & Lauren

- 28th June, ALA, Las Vegas, panel, signing, banquet

- 10-13 July Readercon, Burlington MA (Just Ada, no Jo)

- August 14-19 Worldcon, id est Loncon3, London, England

That’s it for today. Tomorrow I will have a full post up, discussing an exciting new novelette, and in a few weeks we’ll have more Skeptics, once I’ve escaped the stack of deadlines that are looming on my desk all saying “May!”