Medical Leave Reflections plus Empathy Sphere Essay

Good news first, I have a new essay out in Uncanny Magazine, “Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a History,” where I talk about my term ’empathy sphere’ meaning the collection of beings we consider coequally a person with ourselves, something which historically has expanded over time, and which is useful in thinking about why when we read old utopias, like More’s Utopia, or early SF utopias, they often don’t feel utopian to us anymore if they don’t have freedom for groups that are inside our empathy sphere but weren’t inside More’s (like lower classes, women, certain races, clones, A.I.s etc.). It’s a useful analytic term and one several people have asked me to write about, and I also give a history of how SF has helped expand this sphere over time. I hope you enjoy reading it!

Good news first, I have a new essay out in Uncanny Magazine, “Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a History,” where I talk about my term ’empathy sphere’ meaning the collection of beings we consider coequally a person with ourselves, something which historically has expanded over time, and which is useful in thinking about why when we read old utopias, like More’s Utopia, or early SF utopias, they often don’t feel utopian to us anymore if they don’t have freedom for groups that are inside our empathy sphere but weren’t inside More’s (like lower classes, women, certain races, clones, A.I.s etc.). It’s a useful analytic term and one several people have asked me to write about, and I also give a history of how SF has helped expand this sphere over time. I hope you enjoy reading it!

Less good and more personal news next, my health has taken a bad turn, bad enough that I have taken medical leave and had to cancel my fall teaching. My medical team is still running tests (U Chicago has an exceptional hospital), and they don’t think it’s life-threatening, but it’s probably a circulatory system issue, with symptoms including severe dizziness, faintness, stumbling & falling, all of which make it very hard to do anything, including teaching. They’re still running tests, and generally hopeful that things will improve, but on a scale of months, not weeks or days. I hope to be well enough to teach in spring. As for writing, I’m doing some, since one of the hard things in this situation is to keep my morale up and nothing nothing nothing makes me happier than writing, but it’s still being slowed, alas, though may pick up a bit as the glut of start-of-leave tasks diminishes.

So I wanted to share some reflections on this.

One is that it is amazing how much of the resistance to taking medical leave came from me, not others. Even when friends, colleagues, disability staff at the university, and family were all encouraging it, even when I confirmed my employer policies meant I could do it w/o a bad hit to income etc., even when I was in the doctor’s office and the doctor checked a couple things and the first words out of her mouth were, “Well, you can’t work!”, even when the doctors took it so seriously they wouldn’t let me walk out of the office but insisted I wait for a wheelchair, I still immediately started protesting about, “Well, if I teach remotely from lying down… but this course is special… but if I have X accommodation…” etc. arguing back even against such reasonable arguments as, “Your body is failing to deliver oxygen to your brain! You know what you need to do anything?! Oxygen for your brain!” Nonetheless, it took many days, much encouragement, and many repetitions of exhaustion & collapses for me to decide that, yes, everyone urging me to take medical leave did indeed mean I should take medical leave. (Important principle: in teaching all courses are special/unique, if you make exceptions for that you’ll never stop making exceptions.)

Where did my resistance to taking medical leave come from, when I was in the extraordinarily fortunate position of my employers, doctors, and family all being 100% supportive? (a rare and lucky thing). Partly it came from not wanting to let others down, partly from not wanting to admit to myself that it was serious, but a big part of it also comes from narratives, from The Secret Garden, from Great Expectations, from a hundred other narratives, some classic some recent, in which chronic illness/weakness/invalidness is all in one’s head, or where it’s “overcome” by force of will or powering through the pain, so that even in the fortunate case where everyone around me was being supportive and great, those narratives of powering through were unconsciously deep inside me feeding my resistance to accepting that my doctors and employer aren’t exaggerating when they say, “Don’t work.” This connects to something I discussed in my second-most-recent Uncanny essay, on the Protagonist Problem, that it’s very important to have a variety of narratives and narrative structures, and it can do real harm if one type of narrative or structure dominates depictions of a topic. Some versions of this have been discussed a lot recently: back pre-Star Trek, when close to 100% of black women depicted on TV were housemaids, it did harm by reinforcing bad stereotypes & expectations; similarly today when a very high percentage of immigrant characters depicted on TV are shown committing crimes, it feeds bad expectations. In the Protagonist Problem essay I argue that it also does harm when a large majority of our stories show the day being saved by individual special (often chosen one or superpowered) heroes, since it feeds a variety of bad impulses, including the expectation that teamwork can’t save the day, and feelings of powerlessness if we don’t feel like heroes; the argument isn’t that protagonist narratives are bad, it’s that protagonist narratives being the vast majority of narratives is bad, because any homogeneity like that is bad, just as it’s important for us to depict many kinds of people being criminals on TV, not a few kinds overrepresented and others erased.

Thus, for disability, we also have a problem that depictions of disability tend to repeat a few stock narratives, not one but three really, which together drown out others and dominate our unconscious expectations. One form is is the disabled/disfigured villain, a holdover from pre-modern ideas about Nature marking evil with visible indicators (and virtue with beauty). Another is a person falling ill and dying, a tragedy, which ends up focusing on the friends and loved ones who help along the way, or who survive. Another is ‘inspiration porn’ (David M. Perry has great discussions of this) which has a few varieties but tends to focus on how heroic an abled person is for helping a disabled person achieve a thing (like Secret Garden where she gets him out of the chair) instead of on the disabled person’s achievements/experience, or to present “Look a disabled person did a thing!” but in a weirdly dehumanizing way, the same way you would write “Look, this monkey can play chess!” All of these make people resistant to accepting the label disabled, since, even though it’s really useful once you have (I had trouble for a long time) we associate it with being morally bad, being doomed, or being helpless and dehumanized.

The disability narrative most relevant in my recent situation, though, are the stories of ‘overcoming’ disability, where a person is either cured (through their own efforts or others’), or works hard and pushes through, so the disability becomes a problem of the past, that has been left behind. This often-repeated narrative (present in fiction and nonfiction) encourages the attitude of seeing disability’s disruptions to life as temporary and surpassable. It means that, when I get a new diagnosis, my first thoughts even this many years into having chronic illness, are always about how long it’ll be until I overcome it, what I need to do to get past it, the expectation that it’ll be normal by spring/summer/December/whatever. This often leads me to delay by weeks or months or longer taking steps to, for example, adapt my home to be more comfortable (like getting a lap desk so I can work lying down), and other changes dependent on expecting the condition to be here to stay. I think, as a culture, we really hate telling stories about illnesses and disabilities that are here to stay.

I remember a conversation with a friend once about a situation where a medication good at treating their particular condition was taken off the market, and the parents of a kid with the condition contacted my friend to ask how to advocate or find other ways to get more of the medication, and the friend had to keep saying no that wont’ work, no you can’t get it, no you really can’t get it, no your doctor can’t write a special note, until finally they asked directly, “So what do we do now?” to which my friend answered, “Accept a lower quality of life.” That phrase crystalized things for me. I think in many ways no ending is scarier for us in narrative than accept a lower quality of life. It isn’t a one-time tragedy like death, we have good narrative tools to write tragedy, and to transition focus to the characters who live on, commemorate, remember. Accept a lower quality of life in a story means losing, giving up, surrendering, all the things we want our brave and plucky characters to never do, and then having to live with every day being that much worse forever. It’s neither a happy ending nor a tragic ending, it’s a discouraging ending, and we rarely tell those stories.

I vividly remember the first story like that I ever met, it was a James Harriot All Creatures Great and Small story, about a man whose family had been coal miners, who really wanted to farm, and bought a farm, and worked tirelessly to do a good job, and was a really nice person and always kind and earnest (unlike a lot of the characters in the stories), but then his cows got sick and James tried everything he could to cure them but it didn’t work, and then the farmer came to tell him, with a calm demeanor, that he was selling the farm and had always promised his father he’d go back to coal mining if “things didn’t work out” (coal mining which in the 1920s-30s meant a much shortened life expectancy as well.) James realizing how huge this was (accept a lower quality of life) despite so many efforts said, “I don’t know what to say,” and the farmer answered, “There’s nothing to say, James. Some you win.” I still tear up just thinking of that scene, the cruel unspoken and some you lose applied to a whole long life-still-to-come, every day of which would be worse, and there was no other way. A big part of modern advancement is about avoiding there being no other way–offering insurance, social safety nets, appropriate grants–but it’s also an important type of story to tell sometimes, and one I really needed some examples of. Why? Because those stories, those phrases in my memory (some you win, and, accept a lower quality of life) are not where I think I am now, I’m still working hard on treatments and therapy etc., but I needed to have them in my palette of expectations of things that could be the case, to help me plan. I needed those at the start of term to get out of the, “But surely it’ll get better in a couple weeks if I work hard,” mindset to the better attitude of, “The doctors don’t know how long this will last, I’d better plan in case it lasts a long time.”

If the only outcomes in our expectations are (A) powering through and it gets better, or (B) death/villainy/helplessness-forever, none of those archetypes will give us the sensible advice that it’s wise to plan long-term just in case there is a long-term thing that impacts quality of life. Because today a lot of those can be addressed with adapting tech/stuff/habits. I put off buying a lap desk for 2.5 months this summer, struggling to work lying down, since I didn’t want to waste the money if I was about to get better. But having a lap desk and turning out not to need it is much better than needing one and grinding on without. I also put off adapting the area around my bed to optimize for work, put off getting the new screen which finally today (Oct 7, I started wanting this in July!) got installed so I can have multiple monitors while lying down. I put off realizing that instead of watching chores pile up expecting to catch up when I got better, the household needed to discuss and make changes to reduce the total load of chores (simpler meals, paper plates, self-watering planters, planning! Also: thank you so much Patreon supporters, you made my new lying-down desk and canes and such possible!!).

The some you win stories are extremely sad and shouldn’t become our dominant narrative, but they need to be in the mix, one color in the color wheel, to help people who do face disability to weigh the odds better, and not think well, in 90% of stories I know the person gets better so probably I’ll get better and this [desk/ screen/ cane/ adaptation] is likely to be a waste of money. Because you now what’s a good thing even if the end of one’s real life story is accept a lower quality of life? Accepting a quality of life that’s only 5% lower instead of 20% lower because you’ve adapted your home/ routine/ desk/ fridge/ breakfast routine etc. to mitigate as much of the negative impact as you can. So here I am in what is probably the best possible lying-down desk, writing and producing more than nothing, but I sure would’ve produced more over the last few months if I’d done this sooner. And I also would’ve been a lot more willing to say “You’re right I should take medical leave,” if I had believed my odds of recovering quickly were, say, 50/50, instead of, as narrative tells me, expecting that if I tried hard it was certain that I’d quickly power through (and that if I didn’t recover quickly that heralded either moral weakness, helplessness, or death, three things our minds work very hard to resist). A broader mix of disability narratives whispering in the back of my unconscious mind, telling me there might be many outcomes and I should plan for many outcomes not just for the best, would have done so much good–that’s why we need variety.

As a coda to this discussion, chatting about it with Jo Walton, she pointed out that both my examples of accept a lower quality of life stories are nonfiction (Herriott’s fictionalized from real life, the other just real life), and that after she and I first discussed the Herriott story she tried hunting for examples of that kind of story far and wide but basically never found them, that she often found it as “a Caradhras, a mountain you can’t get over so you go under, never the end.” But recently she found several examples in the work of the extremely obscure and neglected Victorian writer Charlotte M. Yonge; it’s great to find one, but also to have confirmation from a voracious reader about how rare such narratives genuinely are.

As a coda to this discussion, chatting about it with Jo Walton, she pointed out that both my examples of accept a lower quality of life stories are nonfiction (Herriott’s fictionalized from real life, the other just real life), and that after she and I first discussed the Herriott story she tried hunting for examples of that kind of story far and wide but basically never found them, that she often found it as “a Caradhras, a mountain you can’t get over so you go under, never the end.” But recently she found several examples in the work of the extremely obscure and neglected Victorian writer Charlotte M. Yonge; it’s great to find one, but also to have confirmation from a voracious reader about how rare such narratives genuinely are.

Now, my other reflection is on academia not disability things.

When I finally decided on taking leave I joked to myself, “For academics, ‘vacation’ means when you do the work you really want to do, and ‘medical leave’ is when you actually vacation.” But the reality is that even medical leave I’ve been finding myself doing minimum four hours of academic work a day, sometimes much more. It has been an interesting chance to see, both which specific parts of academic work absolutely can’t be cancelled or handed off to others, and just on the sheer volume of time that academics are required to give to things which are neither teaching nor research. Letters of recommendation wait for no man, ditto letters for other scholars’ tenure files, and mentoring meetings with Ph.D. students about their urgent deadlines; it’s one thing to set aside one’s own agenda but another to neglect things that other people really depend on. So here I was on full disability leave, with all teaching and research obligations on hold, something my university was quickly able to give, and yet I found myself working intensively from waking until dinnertime and still falling farther and farther behind even when the only work I did was letters of recommendation and inescapable paperwork. In other words, at least when rec letter season is upon us, the paperwork and mentoring parts of academia are pretty close to a full 9-to-5 job even without teaching or research! And that is for someone tenured at U Chicago, one of the most privileged teaching positions in the world, with a light load at a very supportive university.

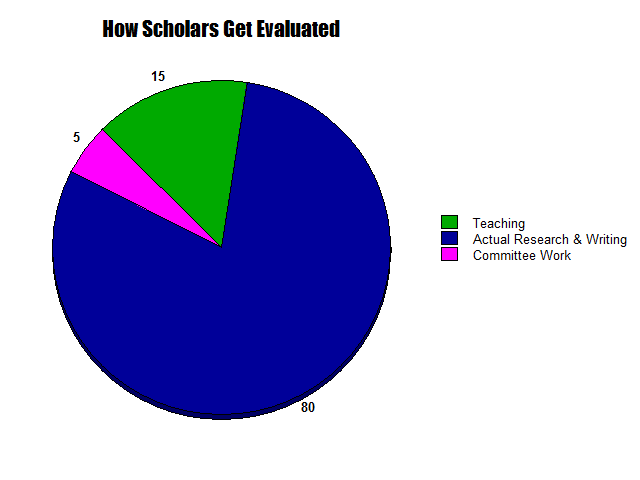

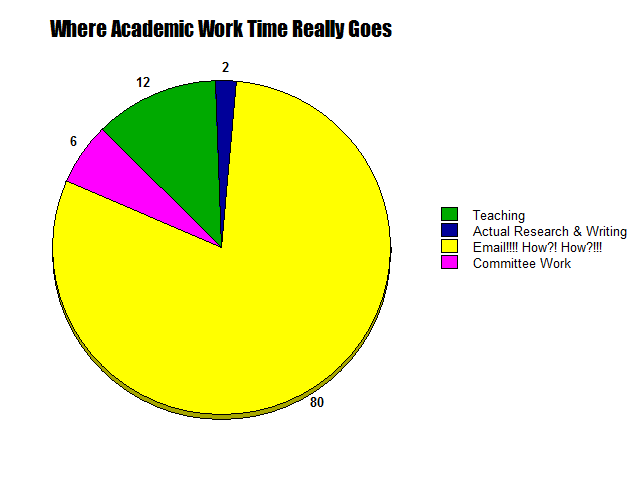

As one friend put it, “I’m not a teacher, I’m a full-time e-mail answerer,” another, “I teach for free, it’s the grading and admin they pay me for,” another, “You can either produce research or keep up with email, but you can’t do both.” We need to factor this in as we think about how academia functions and what reforms to push for, and into how we teach Ph.D. students since things like email skills and time-management skills are absolutely essential to teaching and research when they need to be balanced basically like hobby activities squeezed into the corners of time we can scrape out around the full-time job of admin. It doesn’t have to be this bad. Possibly the problem is best summarized when I was talking to people about a high-level search committee (i.e. hiring at tenured full professor level instead of junior level) and they said they weren’t going to ask for letters of recommendation until they got to the short list of finalists and would only ask for letters for those few, not everyone, “Because we want to respect the time of the important people writing the letters.” Subtext: we don’t respect the time of the less-high-status people writing the many hundreds more letters needed for junior hires. I genuinely think every academic field would produce another 80+ books per year if we just switched to only requesting rec letters for finalists instead of all applicants, and that’s just one example of a small change. In sum, anyone near academia needs to acknowledge that the real pie chart of academic work is depicted below, that we need to plan for that and remember that small changes to self-care or workflow (just studying up on gmail tag and shortcut things for example) can make a huge difference to reducing the unreasonable load and avoiding burnout, and above all that we should always remember that phrase–respect the time of the people doing X–when we plan how to organize things (syllabus, meetings, forms, applications, committees, etc.). And I’m sure a lot of this applies far beyond the academic world as well.

Meanwhile, between recommendation letters I can’t get out of writing, plus disability paperwork, doctor’s appointments, and working on getting my home adapted so my quality of life is diminished by a little instead of a lot in my present state, I’m definitely working-rather-than-resting more than 40 hours a week, and that’s a pretty typical illness experience. It’s good to know that going in, accept it, plan for it, carve out time for the inescapable tasks and to think of adapting the home as time-consuming (or something we should ask for help with!) Otherwise it’s very easy for a week, or month, or three months of ‘rest’ to be not at all restful, and the hoped-for ‘recovery’ to remain elusive. I still have three months of leave before me and I’m definitely leveling up at how to make my leave actually be leave (delegating, adapting things, finding others to write letters when possible) but learning how to make leave actually be leave, and rest actually be rest, is definitely a skill one must level up at, and I think if we understand that it’s a skill (and perhaps tell stories about it?) we’ll be better at realizing we need to actively work to learn it when we (or loved ones) need that skill.

So, for now, I’ll be focusing on rest, and doctor’s appointments, and home adaptation, and things to keep my morale up, and writing (keeps morale up!), and getting ready for the release of Perhaps the Stars (!!!!!!!) but I hope these reflections are helpful, and many thanks to everyone who’s been supportive & helpful throughout. I’ll see you soon when I’m either (A) better or (B) fully adapted to a partly-but-minimally-lower quality of life.

And if you enjoy my writing don’t forget about the Uncanny essay: “Expanding Our Empathy Sphere Using F&SF, a History.”

10 Responses to “Medical Leave Reflections plus Empathy Sphere Essay”

-

I highly recommend the small Pendle Hill pamphlet “Hallowing One’s Diminishments” by John Yungblut a “weighty” Friend.

Rosalind Smith described it best in “the Friend: the Quaker Magazine.”

–When John Yungblut’s life began deteriorating after a diagnosis of Parkinson’s, he soon saw that his ‘first step in learning to “hallow” the progressive diminishments in store for me was a deep-going acceptance’. But it would have to be a positive rather than a negative one, if it were to be a real hallowing. He learnt to cooperate with the process by maintaining a friendly attitude toward it, an understanding that it was ‘part of the process by which I shall ultimately die unto God’. One can learn to treat one’s diminishments as companions, thereby affording oneself a certain detachment – even to develop a sense of humour about them. But he recognises that the forces of diminishment are, in the words of Teilhard de Chardin, ‘vast, infinitely varied, their influence constant’. These forces can be external, the ‘slings and arrows’ that life flings at us; or inward and irretrievable such as physical defects, or intellectual or moral limitations.

-

Thank you for sharing this, and I wish you the best in dealing with your health challenges. Your points about disability and how it’s portrayed in our culture are spot-on. Even as our culture has started to be more open to the idea of “self-care,” as soon as self-care means being less productive in a narrowly defined sense, there are a lot of really ugly societal pressures that come out. And I think it’s important to acknowledge a gendered dimension as well–women are so often pressured to do care work for others where the magnitude of their labor is minimized and taking time for care of the self is stigmatized.

-

Thank you for this luminous reflection on writing and life and the ones you win, and for your generosity and courage. I wish you the best, as always, in making your own story. and I hope your thoughts about work and respecting the time of everyone in this thing of ours find as many readers as your novels.

-

-

Thank you for writing this brave and valuable essay,

I read a lot of Victorian books as a kid, they were there, I was there. They almost all have disabled people in them, just as random characters — Yonge is very good at this. But the one that helped me the most is Cousin Helen in Susan Coolidge’s What Katy Did. Katy falls out of a tree and hurts her back and is an invalid. Cousin Helen is a permanent invalid. Along with the idea that God tried to teach Katy a lesson through love and she didn’t learn it so now he was trying pain, an idea that made me think a lot about theodicy, Cousin Helen shows Katy that you can have a life despite being disabled. Everyone likes Cousin Helen and is glad to see her, even though they have to carry her and she can’t get out of bed. She’s fun, she writes fun poetry, she is a good listener and a good storyteller, and she’s not depressed and self-absorbed. She is more than her disability, and even if Coolidge frames this as living for other people it was still a very valuable thing for me to have in my mind when I became disabled at fifteen. Many disabled people have a horror of becoming boring and only talking about themselves and their disability. Katy was in danger of this and Cousin Helen helped her see that if you are stuck in bed, the best plan is making your bedroom the most fun part of the house where other people want to be. And Cousin Helen confides that she does hate the pain and is afraid, but gets on anyway. And I think with all its Victorian sentimentality and morality having this story in my mind really did help me. Katy gets better, but Cousin Helen doesn’t. I haven’t read this book in at least forty years.

There’s a thing I have a character say in The Just City which I also believe, “We go on from where we are.” We can’t undo the past or start again with a better body, the way Leonard Cohen yells at God in one of his songs. We can’t be perfect, and the thought of perfection and how much one could achieve without x can be discouraging. But going on from where we are, we do what we can.

-

Another thought is that only some of us need these narratives for disability. But almost all of us will grow old, and we also have terrible narratives for getting old and slowing down, where “accept a life 5% worse instead of 50% worse” would be a very useful tool.

-

Hi Ada, thanks for your generous, open-hearted sharing of your recent experiences. As always I found reading of them personally rewarding.

I wondered if it had occurred to you just how relevant this is to the world right now in that the ‘accept a lower quality of life’ is what so many struggle with post-COVID and in the climate crisis?

The most likely outcomes for both is just that, but political leaders cannot articulate it, and have not tried since the beginning of the pandemic, and dare not on climate change in case it frustrates the responses to minimise impacts, even though over the long term we would benefit by having the greater understanding of where we are likely heading.

Writing in Australia we are experiencing these dissonances acutely A) because we managed to minimise the impacts in the early stage of the pandemic, and B) because on climate change our political leaders have concentrated so much on what we will lose in transitioning to renewable energies (when we produce so much fossil fuels) rather than a discussion of the impacts of climate change on our population.

With regards the pandemic, I will be closely observing how the vaccinations ‘hold the line’ and protect populations in the northern hemisphere as we head into the critical Winter period as an indication of how much it will lower our quality of life as measured in life expectancy and measures required to keep especially vulnerable groups safe to societally-accepted level until science takes us back to where we were before, or more likely, our expectations are permanently reset lower and we do do not recognise it for what it is (of course a certain amount of this reset has already occurred, proportionate with the direct impacts from the pandemic on various societies, first, and then globalised through the usual culture-exchange channels).

All the best, thank you, and take care.

-

Surprised neither you or Jo thought of Miles Vorkosigan as an example of accepting lower quality of life. The damage he takes in later books is never cured – instead he needs to use awkward devices to mitigate his seizures, and later uses a cane and moves stiffly, but both of these are evidences of past triumphs because the damage didn’t kill him.

-

I’ve been thinking about why I didn’t, and the answer requires giant spoilers but the short answer is that Miles never ever allows “some you lose” to cross his mind, even when he has lost and is sitting in the sand with splinters of bone everywhere he ends up (a whole book later), where he wanted to be, on the other side of the wall. And he keeps doing things that have consequences, certainly, but even after his growing up book, Memory, we see him ignoring limits and pushing on, and thinking he can overcome the physical with his brains, even when it doesn’t work we see him trying it with the joystick in Diplomatic Immunity. I love the Vorkosigan books, and I actually love the portrayal of disability and I find it very realistic, but it isn’t offering any kind of acceptance story shape even where that would be rational. I wrote a tor.com piece about Aral called “Those Two Imposters: How Aral Vorkosigan Dealt With Triumph and Disaster” and I think Kipling’s impossible demands of a man in “If” are really a thing the series is grappling with interestingly. But the author is on the side of the characters even when she’s putting them through a lot, and the only time Miles comes up against this kind of “accept a lower quality of life” it is half-way through Memory and it is a thing he has emotionally surmounted by the end, even if — you’re right — he does still has to live with the seizures.

-

-

[…] scary aliens, false utopias and real utopias, stories where we cure the plague and stories where we accept a lower quality of life. We even need some purity stories since—as Shotwell obesrves—purity is a very useful and […]

-

“Accept a lower quality of life in a story means losing, giving up, surrendering, all the things we want our brave and plucky characters to never do, and then having to live with every day being that much worse forever.”

I see this idea at work in romance novels, especially historical or pseudo-historical ones, but it is always through the lens of a secondary character being contrasted with the main character’s superior privileges and lifestyle choices. For example, that moment in Pride and Prejudice when Elizabeth talks to Charlotte, who has just accepted a marriage of convenience to Mr. Collins. Or in a modern chick-lit, maybe it’s the main character visiting their mother or girlfriend or former bestie with their less-than-stellar mate and unhappy home life, just to remind them that this isn’t the future they want. It’s used as a threat. Even in arranged-marriage stories, the focus is on the fact that this *is* romance after all, just coming in a forced and initially unappealing package, usually, rather than an actual downgrade in quality of life.

Of course, with divorce on the table, the threat of ending up with a seriously flawed life partner forever is not as absolute a threat as it used to be. But all people are flawed at least a little bit – maybe if more stories centered on married life, they would be more likely to include elements of a romantically oriented lower-quality-of-life story.