Spot the Saint: The Four Evangelists

We still have plenty of saints to cover, now that the Machiavelli series is done.

We still have plenty of saints to cover, now that the Machiavelli series is done.

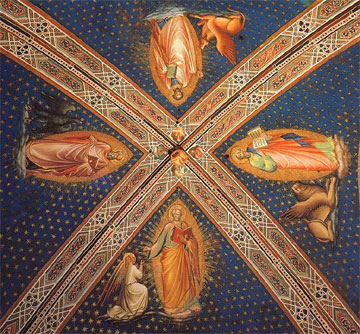

In the last edition of Spot the Saint I discussed John the Evangelist, common in crucifixion scenes and in paintings that want an excuse to show a comely young man. But another common reason to depict him is when one, for aesthetic symmetry purposes, wants a set of four saints to depict, often for architectural purposes: decorating a row of four vaults or four arches, in the four corners of a frame, on the four sides of a dome or a cabinet, etc. The four Evangelists serve perfectly, and in Florence at least one sees Matthew, Mark and Luke far more often in the set of four than one sees them individually; John is the exception. I will thus briefly discuss each of the remaining three gospel-writers, and then treat how one spots them when they’re together.

Each of the four Evangelists has a special symbolic animal, making the set very easy to spot. The animals come from Revelations 4.7, and their connection to the Evangelists is… vague but firmly rooted in iconograpic tradition. Any given Evangelist is often sitting near or on his animal, or has the animal as a decorative motif in the frame. Sometimes the animal alone is used to depict the saint. These animals are always winged, and sometimes covered with eyes. Spotting the four in a set makes the Evangelists easy to pick out. The four are a Lion for Mark, a Bull for Luke, an Eagle for John, and a winged person i.e. an angel for Matthew.

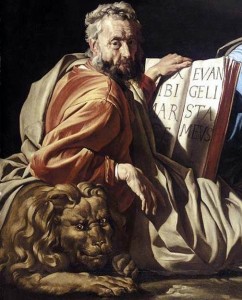

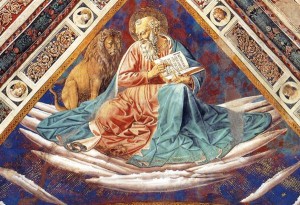

Saint Mark (San Marco)

Saint Mark (San Marco)

- Common attributes: Winged Lion, book, long white beard

- Occasional attributes: Inscription saying “Pax Tibi Marce Evangelista Meus”

- Patron saint of: Lawyers (Barriesters), Venetian Sailors

- Patron of places: Venice, Egypt, Alexandria

- Feast day: April 25th

- Most often depicted: Writing in a book while looking dower, being a winged lion, riding a winged lion.

- Relics: Venice. (Venice: “We have him! You can’t have him! Wa haha! Wa hahahaha!”)

Setting aside the technical biblical details about who Mark started as (which never appear in art), St. Mark seems to have served as an interpreter and traveling companion for Peter for a while, transcribing his sermons (which turned into the Gospel of St. Mark), and thereafter founded the Church of Alexandria and eventually served as its bishop. The Church of Alexandria later evolved into the Coptic Church (notable for leaving us many exciting manuscripts and for coming up with the brilliant idea that instead of writing in long scrolls you could bind pages of writing together into a rectangular structure called a “codex” which we recognize as the modern standard book) so Mark is extremely popular with the surviving Coptic Church, and there are late Coptic stories that he might have been martyred by having a rope tied around his neck and being dragged by it through the street until he was strangled, but this is quite apocryphal so there are fairly few Italian paintings of it.

Mark is particularly prominent in Italy because he is the patron saint of Venice. In 828 AD, Venetian sailors stole Mark’s relics from Alexandria and took them to Venice, where they are now housed in the stunningly expensive Basilica of St. Marco. Venice is excessively proud of this, so much so that the front of said Basilica boasts a mosaic featuring the theft. This may seem strange, but stolen relics were particularly prestigious in the pre-modern world. When a relic was stolen it was “The will of the saint,” whereas if it was bought then human greed and avarice made the acquisition less holy. Mark wanted to be in Venice, is the logic, which is why he arranged to be stolen. Theft also proves power and conquest, and the rest of the Basilica is built from expensive colored marbles looted from Constantinople when the Venetians conquered it, thus advertising Venice’s wealth and military prowess as well as their piety.

The winged lion of St. Mark is thus the symbol of Venice, and they put it on absolutely everything. In fact, if lost in Italy you can usually tell how close to Venice you are by the steady increase in winged lions as one approaches the lagoon. So enthusiastic is Venice about the winged lion that, when called upon to create a three-part symbol representing the city, its land empire and its sea empire, the government settled on a winged lion standing on land for the land empire, a winged lion standing on waves for the sea empire, and a third winged lion in a different pose in the middle for the city itself. So powerfully was St. Mark associated with Venice in the Renaissance that, if you ever see him depicted outside the context of the set of four, smart money says there are Venetians about. Even in Rome you can spot Venetian-built buildings by the winged lions all over them, and anywhere once ruled by Venice is saturated with them.

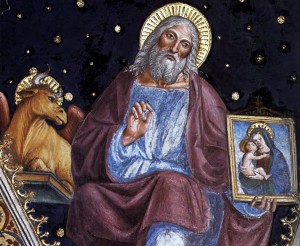

Saint Luke

Saint Luke

- Common attributes: Winged ox, book, beard.

- Occasional attributes: Paintbrush, surgical tool, icon of the Virgin and Child.

- Patron saint of: Artists, sometimes doctors, surgeons, notaries, historians, butchers.

- Patron of places: Padua

- Feast day: October 18th

- Most often depicted: Painting the Virgin, sitting on a winged bull, being a winged bull.

- Relics: Padua, with a piece in Thebes.

Luke came from Antioch, in Syria, and is credited as author of the Gospel of St. Luke and of the Acts. He is described as having been a doctor, but is not particularly associated with doctors or generally invoked as their patron becuase, unlike Cosmus and Damian, he did no medical miracles. He is often discussed as an historian, since the books credited to him seem to contain an unusual amount of historical and geographical detail in addition to describing events he did not himself witness and must have researched. His status as an historian is thus a product of later scholars noting the difference in his tone from other bits of the New Testiment. Debates over whether or not Luke counts as an historian have been fought a lot, especially in the 19th and 20th centuries, and are something of a nexus for arguments over what an “historian” is, i.e. can someone whose work had a specific persuasive goal be called an historian? An interesting debate.

Even more divorced from textual sources but far more important in visual depictions of Luke is the idea that he was a painter. He is supposed, according to Medieval tradition, to have painted the first religious icon, a portrait of the Virgin Mary, painted either while she was alive or while she visited him in a vision. The incredbly monotonous and identical icons of Mary which proliferated throughout the Middle Ages and, in the East, even later, were supposed to be copies of his, and their slavish dedication to being as identical as possible was motivated by the desire to preserve the authentic original. Icons supposed to be the original painted by Luke pop up from time to time in the Renaissance, often brought home to places like England from Italy, or farther east. When shown solo, saint Luke is most commonly depicted as an artist, and one of the most popular tricks is to paint St. Luke painting the Virgin, so one gets to paint her, him, accompanying angels, plus the canvas with his unfinished portrait.

Even more divorced from textual sources but far more important in visual depictions of Luke is the idea that he was a painter. He is supposed, according to Medieval tradition, to have painted the first religious icon, a portrait of the Virgin Mary, painted either while she was alive or while she visited him in a vision. The incredbly monotonous and identical icons of Mary which proliferated throughout the Middle Ages and, in the East, even later, were supposed to be copies of his, and their slavish dedication to being as identical as possible was motivated by the desire to preserve the authentic original. Icons supposed to be the original painted by Luke pop up from time to time in the Renaissance, often brought home to places like England from Italy, or farther east. When shown solo, saint Luke is most commonly depicted as an artist, and one of the most popular tricks is to paint St. Luke painting the Virgin, so one gets to paint her, him, accompanying angels, plus the canvas with his unfinished portrait.

Luke’s relics were in Ottoman hands for a long time, but were brought to Europe as part of the dowry of a Serbian princess and then sold to Venice sometime close to 1500. Venice put the relics in Padua, the city closest to it on the mainland, its most constant and important subject city and the home of its university. The relics were examined by scientists in the 1990s (when the Eastern Church asked for a piece back to put in his tomb in Thebes, a request which was, in fact, granted) and the bones seem to be of the right place and period. His animal is the ox, for which reason he is occasionally a patron of butchers.

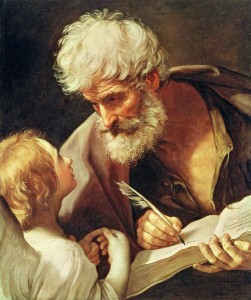

Saint Matthew

Saint Matthew

- Common attributes: Book, beard, accompanied by a small angel

- Occasional attributes: Money bag

- Patron saint of: Tax collectors, accountants, other people who handle money, perfumers

- Patron of places: Salerno, Trier (Germany), Washington DC

- Feast day: Sept. 21, Nov 16

- Most often depicted: Writing his gospel

- Relics: Salerno

Matthew was a tax collector before converting to writing and preaching. Tax collectors were not well-liked at the time, so he is taken as an example that Jesus wanted to call bad people as well as good. In addition to the Gospel of St. Matthew, many now-officially-apocryphal writings were attributed to him, and he is one of few Apostles whose existence is firmly accepted in the Muslim tradition as well. Everyone agrees he evangelized in Ethiopia. We don’t know that much about Matthew’s life and he has few extra adventures credited to him by the medieval tradition, so is rarely depicted at all except with the set of the other three. A man in apostolic (i.e. vaguely Roman) robes with a beard, a book and an angel is often him, but might be any number of other people, so it’s best to see if his three companions are nearby before making a firm guess. His relics are the pride of the city of Salerno, in a very early cathedral, constructed in the 1000s.

The fourth, of course, is John, who, when in the set with the others, usually has his eagle, and is usually depicted in his old man state to match the other three.

The fourth, of course, is John, who, when in the set with the others, usually has his eagle, and is usually depicted in his old man state to match the other three.

Evangelists are usually easy in Spot the Saint, particularly since they travel in a set, but occasionally you get one by himself just standing there with no animal or nothing: bearded man in apostle-looking robes with book. Sometimes the first line of the relevant gospel is written on the book, so if you have memorized the Latin Vulgate translation of the first sentence of each you can tell who’s who, but few of us today have. Failing Latin, in such circumstances the best way to figure out who it is is to think about where you are, or where the painting is from. Are you, perhaps, standing in a monastery named “San Marco”? Or looking at a painting made in Venice? Or Padua? If so, you can make a pretty confident guess. Sometimes, though, the best you can do is: “There are two apostle-looking guys discussing a book. They’re probably evangelists, most likely Mark and Luke since they’re the most popular.”

The Evangelists are also a good way to get yourself used to spotting what apostles dress like, which is to say they are always in Roman-ish robes, with a colored drape of one color over a floor-length tunic/robe of a second color. This uniform is exclusive to saints of the Roman era and pretty exclusive to apostles, so is a good taxonomic way to narrow things down. Is the mystery saint dressed like an Apostle? If so you can rule out a huge portion of saints.

And now, Spot the Saint Quiz time.

First, since it’s been a while, a brief review of everyone we’ve seen so far, so you have the possibilities fresh in your mind. See if you can remember one or two attributes for each:

-

Sometimes Evangelists’ animals don’t have wings! Saint John the Baptist

- Saint Lawrence

- Saint Sebastian

- Saint Catherine of Alexandria

- Saint Peter

- Saunt Paul

- Saint Zenobius

- Saint Reparata

- Saint Dominic

- Saint Peter Martyr

- Saint Thomas Aquinas

- Saint Francis of Assisi

- Saint Antony of Padua

- Saint Bernardino of Sienna

- Saint Nicholas of Cusa

- Saint Agatha

- Saint Lucy

- Saint John the Evangelist

- Saint Mary Magdalene

- Saint Mark the Evangelist

- Saint Luke the Evangelist

- Saint Matthew the Evangelist

And now the quiz, a Fra Angelico fresco from one of the cells in the gorgeous monastery of San Marco in Florence, a political hotbed of a monastery, patronized and paid for by Cosimo do Medici but later the seat of Savonarola. All but one of the figures in this image are figures we have discussed. The last one is St. Benedict, founder of the Benedictine monks, here depicted unhelpfully without his usual attribute, a bundle of canes to flog novices with. You should still be able to tell which he is. Throwing one’s hands up as the saints are doing is a gesture of surprise and awe.

10 Responses to “Spot the Saint: The Four Evangelists”

-

my lords glory

-

‘Each of the four Evangelists has a special symbolic animal’

Really? And which animal would you attribute to St. Matthew?

Last thing I thought I’d find in your (otherwise) wonderful blog. -

Anna, yes, apologies if the term is ambiguous.

Matthew’s “symbol” is the angel that accompanies him. When discussing the four evangelistic symbols in an art history context we often use the shorthand “animal” for the four (Ox, Eagle, Lion, Angel) because it’s pretty clear that when you say, “Ah, the animals of the Four Evangelists!” you mean that, whereas if you say “Symbol” you could mean any number of things in the piece of art which serve as symbols (books, letters, family crests etc.) It is indeed a bit of a stretch to apply “animal” to the angel, but it’s still a useful shorthand.

(I’ve heard some discuss Matthew’s companion as a “winged human” comparable to the “winged lion” etc. and argue that human is an animal, but setting that aside, I genuinely think when people say “The four Evangelistic animals” they usually, as I do, mean it as a clarifying shorthand and aren’t making some complicated theological point about angels, humans, animals and the malleability of the Ladder of Being.)

-

Can we use these images. Are they public domain?

-

While the photos of architecture and places on this site are my own, the photos of art are harvested from around the web, mainly from Wikipedia. They should all be public domain but I don’t have the legal authority to say “yes, you can use them.” If you’re looking for good photos of Renaissance art and architecture, and of saints, I recommend going to Wikimedia Commons.

-

I would like permission to use photo of Evangelists in my book, Magic in Art. It is the first photo of your Exurbe article dated ‘Spot the Saints” showing the four evangelists as eagle, lion, man, and bull. The illustration shows how animals were used to identify apostles during medieval times. My books investigates the use of symbols in healing, and includes use of symbols in religious context.

-

Unfortunately I didn’t take that photo myself, I borrowed that from another here online. I can’t give you permission.

-

-

Hi there, nice blog! I would like to pint out that the Saint Patron of Padua in Italy is Saint Anthony, not Saint Luke.

About Saint Mark, the Patron of Venice… yes, technically he was stolen, however, the Calif Mamum was starting to use the Christian churches in Alexandria as a source of materials for his mosques. The tribunes Buono da Malamocco and Rustico da Torcello took him to save his body from desecration and because Mark had been evangelizing Aquileia and the Veneto region, before going somewhere else.

For what concerns the lion, there is a Venetian legend that says that Mark wanted to know how thunder and lightening happen. The Lord allowed him to go see, but then he repented and changed mark into a winged lion so that he could come back down to earth but could not reveal the secrets he learned.

The omnipresent lion in Venice can be represented as the “leone andante”, walking on land and sea as a symbol of the power of the Most Serene Republic of Venice over both (google “Vittore carpaccio leone andante” to see the picture that depicts this,) or as the “leone in moeca” (google this for a visual)represented frontally inside a circle and holding the book (written on it the words “PAX TIBI MARCE EVANGELISTA MEUS”). This representation was used on official papers and seals. A curiosity: in time of wars the leone andante is not holding the book, it’s holding a sword.Also, the picture above with the doge depicts the Doge Francesco Foscari kneeling in front of the city of Venice not its patron. The doge in fact was a ruler for the people, first among his peers, private citizen outside the boundaries of the Republic and a servant to the Venice. He was elected for life with a really convoluted system that made it really difficult to cheat.