Sketches of a History of Skepticism, Part I: Classical Eudaimonia

In the last month we have discovered that there are coral reefs near Greenland, that dung facilitates a symbiotic relationship between moths and treesloths, that one of King Arthur’s knights was black, that protons have a different diameter depending on how we measure them, and that the newly-discovered poems by Sappho may undermine what we thought we knew about Greek theories of the soul. And we’re fine with all this.

It is easy for us to forget how the Scientific Method, at work behind all this research, is a uniquely flexible and dynamic belief system, one which enables our uniquely flexible and dyamic world. Some will feel uncomfortable with me calling science a “belief system” but in this context I use the phrase “belief system” as a reminder of what the Scientific Method and its associated aparatus have displaced. Science has not replaced religion–they coexist happily, productively, even symbiotically within many arenas, places and individuals, even as they chafe and vie in others. But in the modern West, the Scientific Method has largely displaced older systems for guiding daily micro-decision-making which were more closely tied to religion. We now use science-based reasoning a hundred times a day when we are called upon to make decisions. Whether making a sandwich, buying a new teapot or evaluating an argument, we think about data from past experiences, bring in what facts and hypotheses we have accumulated from educated and informed living, consider the credibility of sources, ask ourselves questions about plausability, probability, evidence and counterargument, speculate about the range of possible errors and outcomes. We go through many steps, often fleeting but still present, before we assemble our sandwich (which recent nutrition advice seems plausible in the ever-changing range?) or buy our teapot (plastic so housemates won’t break it, or ceramic for environmental/health/aesthetic/flavor reasons?) or decide whether to grant a politician’s argument our provisional belief or disbelief. Even for those members of modern Western society whose lives are powerfully informed by faith or institutional religion, who do seriously factor “What would Jesus/Apollo/Whatever do?” into the calculation, evaluatory criteria based on science and its method remain a substantial, if not exclusive, part of our aparatus for daily decision-making.

For my purposes today, the most important part of what I just described is that the belief or disbelief we extend to the politician (or to our teapot) is provisional. We decide that a thing is plausible or implausible, and extend to it a kind of belief which is prepared for the possibility that we will be proven wrong. That thing the politician said might turn out later to be false (or true) when new information arises. A teapot, let’s say I pick one which claims to be safe and eco-sound because of XYZ carbon something something, it may seem that I have given its claims my complete belief if I buy the teapot, but that too is provisional since my long-term purchasing decisions for other objects will be informed by further information, changes in industry, and, of course, my empirical experience of whether or not this teapot serves me (and survives my housemates) well.

What we knew about teapots, coral reefs, moths and treesloths, Arthuriana, protons, and the Greek concept daimon, can all be overturned and yet we remain comfortable with the Scientific Method which produced our old false information, and we are still prepared to let it provide us with new information, then overturn and replace the new information in its turn. We do this without thinking, but it is in no way a universal or natural part of the human psyche. When chatting with my father about the proton research he summed it up nicely, that two possible responses to hearing that how we measure something seems to change its nature, throwing the reliability of empirical testing into question, are: “Science has been disproved!” or “Great! Another thing to figure out using the Scientific Method!” The latter reaction is everyday to those who are versed in and comfortable with the fact that science is not a set of doctrines but a process of discovery, hypothesis, disproof and replacement. Yet the former reaction, “X is wrong therefore the system which yielded X is wrong!” is, in fact, the historical norm. Whether it’s an Aristotelian crying “Plato has been disproved!” or Bernard of Clairveaux crying “Abelard has been disproved!” or a Scotist crying “Aquinas has been disproved!” the clear overthrow of a single sub-principle within a system was, for many centuries, sufficient to shake the foundations of the system as a whole, and drive people to part with it and seek a new one.

All this is a way of previewing the endpoint of the present series, in order to show how important the often-invisible role of doubt is in current human thought. Without skepticism, and important developments in the history of skepticism, we could not have the Scientific Method occupy the position it does in modern daily lives. So I want to sketch out here some of my favorite moments in the history of skepticism, not a complete history (for that see Popkin’s History of Skepticism or Allen’s Doubt’s Boundless Sea), but the spicy highlights that I’ve most enjoyed.

Dogma and Doubt

There are many ways to subdivide philosophy, but one of the most useful is, in my view, the subdivision into dogmatic and skeptical. I’m using these terms in their technical philosophical senses, so I do not intend to invoke any of the contemporary, negative cultural associations of “dogma” or “skeptic.” (Philosophy and history are constantly plagued with the disconnect between formal uses and modern casual uses of terms like these, Epicurean, Hedonist, Realist, Idealist… and it’s worse when I learn the technical term before I meet the popular one. I can’t tell you how confusing it was the first time I was in a conversation where someone used “libertarian” in its contemporary political sense, which I had never met, having learned it from Spinoza class. Them: “FDR is a big foe of Libertarianism.” Me: “Really? I didn’t know FDR denied the existence of freewill. Was he a materialist? A stoic?” And when I tell my students that, for the purposes of Plato class, “Realist” and “Idealist” are synonyms they sometimes look like they’re about to cry…) For today’s purposes by “dogmatic” I mean any philosophical moment or system which argues that something can be known, or that there can be certainty. By “skeptical” I mean a philospohical moment or system arguing that something cannot be known, or that there cannot be certainty. In this sense, Aristotle’s argument that the existence of a Prime Mover can be logically proved from the principle that any chain of events must have a First Cause is dogmatic, as is the conviction that we know with certainty that the square of the length of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the remaining sides. Pierre Bayle’s argument that God’s existence can be known through faith alone is skeptical, as is the argument that quantum uncertainties like Heisenberg’s mean that material reality can never be fully understood because the act of perceiving it alters it. Thus neither skepticism nor dogmatism is more or less tied to theism than the other – both are broad and diverse categories, and most great intellectual traditions have both in there somewhere.

Dogmatic philosophy is what most people usually think of when we think about philosophy: systems that propose particular things. The Platonic Good, Aristotle’s Categories, Descartes’ vortices and and Heidegger’s Being are all founded in claims that we know or can know some thing or set of things with certainty. Yet skeptical arguments, about what cannot be known, have coexisted with dogmatic claims throughout philosophy’s existence, and the two act as foils to one another, arguing, cross-polinating, hybridizing, and spurring each other on, and their interactions have been among the most exciting and fruitful in philosophy’s long history.

I will begin as close to the beginning as I can:

Happiness in Ancient Greece:

While post-17th-century philosophy often puts its primary focus on the quest to explain and describe things and create a system of knowledge, one key unifying attribute common to just about all classical Greek philosophical schools, though different in each, is the goal of attaining eudaimonia (εὐδαιμονία), from “eu” = good, happy, fortunate, and “daimon” = spirit, soul. It’s usually translated as happiness, but it’s both more specific and stronger. Other renderings that help get the idea across include wellbeing, self-contentment, self-fulfillment, spiritual joy, and personal wellfare. It is the kind of happiness which is deep, lasting, tranquil, reliable, complete, and, in the Greek sense, godlike or divine. By “divine” I mean a list of attributes that most Greek philosophers associated with the gods, who were supposed to be immortal, unchanging, indestructable, eternally happy and satisfied, living in a bliss surrounded by beauties and free from pain. These are not Homeric Greek gods who feud and lust and rage, but more abstract philosophical gods personifying unchanging eternal principles, the sort of gods Plato believed in and for which reason he wanted to censor Homer’s depictions of the more fallible and anthropomorphic ones. The word daimon thus occupies a complex space, much debated, but can be rendered as a spirit, soul or thinking thing, referring to a category vaguely encompassing human souls, gods and intermediary spirits. Thus, eudaimonia is the state of having a happy or fortunate spirit, so my favorite way of rendering eudaimonia is “the kind of happiness Platonic gods experience” i.e. long-term, untroubled, indestructable happiness.

Become a philosopher, lead a philosophical life as I do, and you will achieve, or at least approach, happiness–this is the promise made by every sect, from Epicurus and Seneca to Diogenes and Plato. In the classical world, being a philosopher was much more about life, living well and demonstrating one’s philosophical prowess through one’s personal excellence and successes than it was about writing comprehensive masterworks expounding systems (See Hadot’s What is Ancient Philosophy? and Philosophy as a Way of Life). Each classical philosophical school had its own path to happiness, and each entwined it with different parallel goals, such as the pursuit of personal excellence, or understanding of nature, or civic virtue, or piety, or worldly pleasure, or friendship, any number of things, but we find no classical school for which approaching eudaimonia through leading a philosophical life was not a core promise.

I should note in passing that, in later classical writings, it becomes clear that they take the divine aspect of eudaimonia very seriously, and Neoplatonists especially refer to past philosophical sages as “divine,” arguing that Socrates, Plato, Zeno, Diogenes of Athens, Seneca and so on, had achieved states of philosophical happiness that made their souls identical with those of gods, even while they were contained within mortal flesh. The daimon or soul which is happy in eudaimonia is, after all, categorically the same type of thing as a god, and one of the leading differences between a human soul and a divine one is that the divine one experiences indestructable happy serenity. If a philosopher’s soul achieves the same state, is it not a god? Particularly in a culture which already practiced deification and ancestor worshop? Platonic claims about a philosophical soul growing wings, leaving the body and dwelling among the gods helped further cultivate this impulse. The practice of Theurgy, philosophical magic, developed from the idea that such a divine soul, even while resident in human flesh, could work miraculous effects, such as levitation or generating light.

Now, eudaimonia is a high bar to achieve. Indestructable, god-like happiness must be able to stand unchanged in the face of all changes, a great challenge in a human existence beset by a thousand evils including wolves, tyrants, malaria, civil war, famine, injustice, accidental dismemberment, urequited love, and human mortality. All our surviving ancients agreed that real eudaimonia could not be dependent upon external sources, like fame, wealth, property, physical fitness, romantic love, even liberty of person, because such things could be taken away from you by fickle fate, making them unreliable, and your happiness destructable. I say surviving ancients because we do not have the writings of the Hedonist school, which we know focused on positive, experiential pleasures including, probably, food, drink and sex, and who may have been an exception, but their exceptionality doomed them to be silenced by the dissenting majority. Those who did agree agreed that eudaimonia had to be a state of the thinking thing, the mind or soul, independent of experience, body or social position. It was most frequently connected with things like tranquility, self-mastery, acceptance, and taking enjoyment from things that cannot be destroyed, like Truth. It was also connected with freeing the soul from cares, such as fear, anxiety, envy, ambition, possessiveness, and general attachment to Earthly, perishable things.

These classical philosophical schools developed guides for living and decision-making intended to facilitate a happy life, and those with systems of physics and ontology often tied those closely to their paths to happiness. For example, the atomic explanations for the natural non-divine mechanisms behind thunder and lightning were promoted by Epicureanism as something which could make people happy by freeing them from fear of being zapped by a wrathful Zeus. Thus philosophical disciplines like physics, biology and even basic ontology were in their way tools of eudaimonia as much as they were attempts to explain things. Modern scholars even debate whether, in such cases, the physics was the source of the moral philosophy, or a tool developed afterward to support it when eudaimonia seemed to need it as an ally.

One of the sources of pain and unhappiness from which such systems set out to free people was curiosity, i.e. the unhappiness that derives from hungering for answers. This too needed to be satisfied to achieve the stability of eternal, godlike happiness. The quest to end the pain caused by curiosity meant supplying answers, to questions big and small, but especially big. And they needed to be certain answers, which would be reliable and eternal, and stand up to the assails of fortune, or else eternal, reliable eudaimonia could not rest upon them. This added extra energy to the quest for certainty. One wanted to be really, really sure an answer was right, so one could rest comfortably with it, and be happy, and know it would never change. And one wanted the facts which served as foundations for philosophers’ broader advice on how to achieve happiness to also be certain and unchanging. If Plato says the key to happiness is Truth, Excellence and the Good, or Aristotle proposes his Golden Mean, you want their claims to be based in certainty.

Two tools were employed in pursuit of certainty: Logic and Evidence. All dogmatic claims (i.e. claims of certainty) made by any of our classical thinkers were based on one, the other, or both.

Evidence includes any claims based on observation, sensation, lived experience, or, more technically, empiricism. If Aristotle says bony fish and cartelagenous fish are different because he has dissected a hundred of them and can describe how their insides are different, that is empiricism. If Thales or Heraclitus draw conclusions based on seeing how fire emerges from wood, that is empiricism. If Plato asks us to think about when we’ve seen someone beat a dog and say whether it makes the dog better or worse, that too is a kind of empiricism.

Logic includes any argument based on reasoning instead of sense experience. If Aristotle says that a thing cannot both be and not be at the same time, that is an argument based on logic. If Plato asks us if beating a dog makes it worse with respect to the properties of horses or worse with respect to the properties of dogs, that is also an argument asking us to apply logic.

Meanwhile, in a nearby lake…

Meanwhile, in a nearby lake…

…a stick fell in a pond, and skepticism was born, like Venus, from the waters. Or rather, from someone who saw the water, and saw a stick sticking half-way out of it, and noticed that the stick looks bent or broken at the point where it goes into the water. And yet, the stick is not bent. The person bends over and touches it, just to be sure, and the fingers confirm the wood is whole and strong. My eyes are lying to me! My eyes can’t be trusted! If this stick isn’t bent, what else that my eyes have told me may be false that I haven’t yet realized? What if the sky isn’t blue? Or milk isn’t white? What if trees have faces, chalk is actually as beautiful as gold, and the sky is swarming with exquisite creatures I have no way to detect? And if I can’t trust my eyes, what about my ears? My hands? Sense perception is unreliable! But in that case, how do I know anything I’ve experienced is as I thought it was? Or even that anything is real?! Panic! Panic more! (Quietly in the background Descartes and Sartre are still carrying out the “Panic more!” instruction nearly two millennia later).

The stick in water is a genuine, ancient example, much discused by pre-Socratic philosophers. We don’t know if it’s actually the first example, since the earliest conversations are lost to time, but it may be, and certainly if it isn’t it was something similar, one of the other optical distortions discussed by ancients, like how a square tower can be mistaken for a round tower when seen from a great distance. What does survive is what later philosophers made of these early discussions of the mystery of the stick in water: epistemology, the study of knowledge, how we know things, and when we can or can’t have certainty. The stick in water challenges any claim that the senses can be relied upon as a source of certainty. Forever after, therefore, any philosopher who wanted to make any claim based on sense perception first had to have a way to explain how we could trust the senses despite this, and other, failings.

And the stick in water has a brother: Zeno’s paradoxes. If the stick in water undermines the credibility of sense-perception, its partner, Zeno’s paradoxes of motion, are what undermine the credibility of the other traditional source of information: logic. You have all heard Zeno’s paradoxes before, but rarely in companionship with the stick in water, which is what gives them their oomph, so it’s worth revisiting one here:

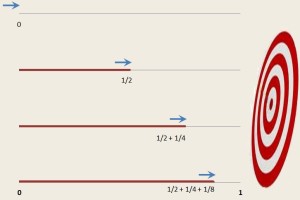

An archer looses an arrow at a target. Before the arrow reaches the target, it must go half way. Next it must go half the remaining distance. Then half that distance. Then half that distance. Half, half, half, half but we can do this forever, so the arrow can never actually reach the target, because it must cross an infinite number of micro-distances first, and nothing can travel infinite distance. Therefore, logically, motion is impossible. Cue polite applause for the logical trick, as at the successful completion of an elegant and challenging ice skating routine. (Cue also Descartes and Sartre glaring at anyone who’s still smiling.)

An archer looses an arrow at a target. Before the arrow reaches the target, it must go half way. Next it must go half the remaining distance. Then half that distance. Then half that distance. Half, half, half, half but we can do this forever, so the arrow can never actually reach the target, because it must cross an infinite number of micro-distances first, and nothing can travel infinite distance. Therefore, logically, motion is impossible. Cue polite applause for the logical trick, as at the successful completion of an elegant and challenging ice skating routine. (Cue also Descartes and Sartre glaring at anyone who’s still smiling.)

Why is this more than a cute trick?

- Youth: “But we know motion is possible, Socrates.”

- Socrates: “How?” (All philosophical dialogs are with Socrates, even when they aren’t.)

- Youth: “Because I can hit you. See?” Hits Socrates.

- Socrates: “Yes, very good. So you know it is possible because you did it?”

- Youth: “Exactly, Socrates. I can do it again if you aren’t convinced.”

- Socrates: “If you want to exercise your will in that way (if there’s such a thing as will) then that’s your choice (if there’s such a thing as choice), but first, perhaps you could explain to me, using logic, how you are able to hit me, if your arm has to cross infinite distance first?”

- Youth: “I… um… I don’t think I can, Socrates. I just know that I hit you, and could do it again.”

- Socrates: “But you can’t explain logically why.”

- Youth: “No.”

- Socrates: “So wouldn’t you say, then, that logic is incapable of explaining motion?”

- Youth: “I guess so, Socrates.”

- Socrates: “Doesn’t that bother you? That logic fails to be able to explain something so seemingly simple? Doesn’t that make you distrust logic itself as a tool? It would seem that logic itself is unreliable and can’t lead to certainty.”

- Descartes (quietly in the background): “Panic more!”

- Youth: “I guess that’s so, Socrates, but it just doesn’t bother me the way it bothers those weirdly dressed men over there.”

- Socrates: “And why doesn’t it bother you?”

- Youth: “Well, because I know that motion is possible because I can do it and see it. I don’t need logic to explain it.”

- Socrates: “So even without logic, you’re sure there is motion… because?”

- Youth: “Well, because when I move my arm to hit you, I can see it. When I touch you with my hand, I can feel the impact, the texture of your skin. I can still feel it a little on my own skin, the spot where it struck yours.”

- Socrates: “So you know there is motion because your senses tell you so?”

- Youth: “Yes.”

- Socrates: “So, since logic is unreliable, you choose to rely on the senses instead?”

- Youth: “Yes. I trust things I can see and touch.”

- Socrates: “Then tell me, my young friend, have you ever happened to notice what happens when a stick falls so it’s sticking half-way into a pool of water?”

Our youth, whom we shall now leave panicking on the riverbank along with Socrates, Descartes, Sartre and, hopefully, a comfortable picnic, has now received the full impact of why Zeno’s paradoxes of motion matter. They aren’t supposed to convince you there’s no motion, they’re supposed to convince you that logic says there is no motion, therefore we cannot trust logic. Their intended target is any philosopher *cough*Plato*cough*Aristotle*cough* who wants to make the claim that we one can achieve certainty by weaving logic chains together. Anyone whose tool is Logic. Meanwhile, the stick in water attacks any philosopher who wants to rely on sense perception *cough*Aristotle*cough*Epicurus*cough* and say that we know things with certainty through Evidence. When you put both side-by-side, and demand that Zeno shoot an arrow at the stick in water that looks bent, then it seems that both Logic and Evidence are unreliable, and therefore that… there can be no certainty!

Don’t panic, be happy…

The double challenge of the stick in water and Zeno’s paradoxes had many effects.

One was to make all classical thinkers who wanted to maintain dogmatic principles work a lot harder to nuance their claims of certainty, to justify why and in what specific circumstances logic and evidence could be trusted, to explain why they sometimes failed or seemed to fail, and how one could reason or observe more carefully in order to achieve greater levels of certainty. Thus these challenges to reason and evidence let dogmatic philosophers adopt skeptical tools and create systems which had space for both dogma and skepticism in the same system, hybridizing the two to achieve greater levels of clarity, complexity, dynamism and subtlety and jumpstarting countless great philospohcial leaps. To give two quick examples, Aristotle attempted to create a system for achieving infallible logical information by saying that logic is 100% reliable if it is based on a combination of (A) unequivocal carefully defined terms, (B) self-evident first-principles, and (C) geometrically-strict syllogistic reasoning by baby-steps. Stick to these and exclude logical leaps and unclear vocabulary and you can carve out an arena for reliable logic, even if that arena is necessarily finite and cannot touch everything. Similarly Epicurus and Aristotle both proposed a kind of empiricism of repeated observation, where we do not trust just one glance at the stick in water but examine it carefully with all our senses, look at many sticks, and eventually draw conclusions we consider more reliable. And at the same time, these same thinkers gave ground and mixed their dogmatism with skepticism by saying that logic or empiricism worked in some arenas but not others. Epicurus, for example, says we can learn a lot from sense data but we can never learn true details of atomic level since we can’t see anything that small. Aristotle similarly says we can learn about the level of the universe that we can experience and think about, the level of the objects we see and contemplate, but not about the chaotic base substructure which underlies the visible and comprehensible world.

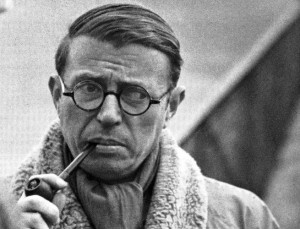

(Sartre, who has just been handed a sandwich by Socrates and is now unconsciously applying the Scientific Method as he considers whether or not to accept Descartes’ offer of mayonaise, looks up here to say that he agrees with Aristotle that there are vast and terrifying unknown depths of being which lie beneath perceived reality. He thinks we should address our long-term attentions to that mystery, and that Aristotle is foolish to cling to pursuing the finite certainties offered by his logic chains and fish observations when no finite knowledge is helpful in the face of the raw unknown infinity beneath. But Sartre is not interested in pursuing eudaimonia, even if he is interested in the short-term, destructable pleasure offered by Descartes’ excellent fresh mayonaise.)

(Sartre, who has just been handed a sandwich by Socrates and is now unconsciously applying the Scientific Method as he considers whether or not to accept Descartes’ offer of mayonaise, looks up here to say that he agrees with Aristotle that there are vast and terrifying unknown depths of being which lie beneath perceived reality. He thinks we should address our long-term attentions to that mystery, and that Aristotle is foolish to cling to pursuing the finite certainties offered by his logic chains and fish observations when no finite knowledge is helpful in the face of the raw unknown infinity beneath. But Sartre is not interested in pursuing eudaimonia, even if he is interested in the short-term, destructable pleasure offered by Descartes’ excellent fresh mayonaise.)

But our ancient Greeks are interested in eudaimonia, and another product of these challenges to reason and evidence, apart from letting dogmatic philosophers hybridize with it, was the birth of Skepticism (big S) as a philosophical school, in addition to skepticism (small S) as an approach. As an approach, skepticism is used by all sorts of thinkers, including Plato and Aristotle in their way, but it was also a school, a rival of Platonists and Stoics. And, like all other ancient schools, Skeptics pursued eudaimonia.

How does doubt lead to happiness? By allowing one to relax and resign one’s self to ignorance, says Pyrrho, the greatest name in pure classical skepticism. We cannot know things with certainty, he says, and this is a release (much as Epicurus thought it was a release to believe there is no afterlife). If we cannot know things with certainty, we don’t have to try. We don’t need to go with Aristotle to the docks and dissect infinite fish. We don’t need to sit with Plato and let him pretend to be Socrates through interminable dialogs. We don’t need to follow Pythagoras and fast ourselves into a trance while contemplating the number ten. We can stop. We can say I don’t know, I can’t know, I’ll never know, no one else knows either, no one is right, no one is wrong (not even people on the internet!), so we can just return to our work and rest. This too, say the skeptics, frees us from pain, from several pains that no dogmatic system can ever free us from. It frees us from the exhaustion of the quest to know. It also frees us from the stress we experience when we turn out to be wrong. If you think you know something, and it’s overturned, that’s stressful and unpleasant. It makes you feel angry, foolish, violated, shaken, abandoned. If you never think you know anything about things, you will never experience the pain of being proved wrong.

You know what the skeptics mean here. You know because you are alive in 2014, and that means you remember when there were nine planets. Weren’t you upset? Wasn’t it distressing and upleasant, shaking your worldview? We learned there were nine planets in kindergarden! Of course Pluto is a planet! Mike Brown, the scientist responsible for getting Pluto’s status stripped away receives hate mail, for precisely this reason: it hurts to be told you’re wrong. And this is far from the only time you, reader, have experienced this. There used to be such a thing as a Brontosaurus. And a Triceratops. (Youth: What! We lost the Triceratops too!”) There used to be four food groups, remember that? And coral reefs used to exist only in the tropics, and moths used to have nothing to do with tree sloths, and you used to have a volume of the complete works of Sappho. And the destruction of all these “truths” have unsettled us to different degrees, because we learned them at different times and they were integral to our worldviews to different degrees. And some we are okay with and with others we smile at the angry t-shirts that say: I remember when there were Nine Planets!

You know what the skeptics mean here. You know because you are alive in 2014, and that means you remember when there were nine planets. Weren’t you upset? Wasn’t it distressing and upleasant, shaking your worldview? We learned there were nine planets in kindergarden! Of course Pluto is a planet! Mike Brown, the scientist responsible for getting Pluto’s status stripped away receives hate mail, for precisely this reason: it hurts to be told you’re wrong. And this is far from the only time you, reader, have experienced this. There used to be such a thing as a Brontosaurus. And a Triceratops. (Youth: What! We lost the Triceratops too!”) There used to be four food groups, remember that? And coral reefs used to exist only in the tropics, and moths used to have nothing to do with tree sloths, and you used to have a volume of the complete works of Sappho. And the destruction of all these “truths” have unsettled us to different degrees, because we learned them at different times and they were integral to our worldviews to different degrees. And some we are okay with and with others we smile at the angry t-shirts that say: I remember when there were Nine Planets!

Now, Aristotle would tell us the strife has been caused by the fact that we had not defined “Planet” carefully enough before, so it wasn’t an unequivocal term, and thus led us to confusion and misunderstandings. “But!” says Pyrrho, “if you had never studied these things, if you had not been taught as a child to memorize dinosaurs, or rest your worldview on the label attached to a hunk of rock far off in the darkness where you never have cause to perceive it, then you would not experience this unhappiness! Your belief that you knew something has made you unhappy, destroying eudaimonia. Just admit that you do not know anything with certainty and then you need never experience such pain again!” And in the case of things we were prepared for–the treesloth and the Sappho and Arthur having a knight of African descent–the Scientific Method told us to do just that, to be prepared for truth to be replaced when it was time, because it was never Truth, it was always provisional truth.

Ten Modes of Skepticism

Many exciting things will happen to skepticism as it leaves Greek hands before reaches ours. It will be transformed by Bacon and Montaigne, by Averroes and Ockham, Descartes will finish his potato salad and have his day, and it has more refinement yet to undergo among the Greeks as well, and from their sunny riverbank Socrates and company will watch skepticism surge over the marble walls of Plato’s Academy like ants into their picnic basket. But for today I want to leave you with a taste of raw classical skepticism, so you can taste it for a little while and have a taste of this oddest of philosophies which proposes un-knowledge, rather than knowledge, as its happy goal. To that end, here, to finish, are examples of the Ten Modes of Pyrrhonism (i.e. the kind of raw skepticism practiced by Pyrrho) based on the handbook of Sextus Empiricus (one of our few surviving ancient skeptical authors). It is a list of categories of sources of error, things that can make you be wrong. Many are ones that we are very well prepared for in the modern world and remain on constant or at least near-constant guard against (though rather than guarding against the errors, what Pyrrho and Sextus want us to do is be on guard against imagining we aren’t making errros, i.e. to be on guard against thinking we know something. I see Socrates is nodding in approval, and that the others are too polite to point out the crumbs on his chin).

The Ten Pyrrhonist Proofs that Nothing can be Known with Certainty:

- We cannot have certainty because different animals have different senses. When do we encounter this? When walking a dog, sometimes the dog stops to sniff in rapt fascination at a spot on the sidewalk where we see nothing interesting. But evidently there is something very interesting there if a creature as intelligent as a dog is fascinated, and willing to disobey its friend and choke itself by pulling on its collar in order to study this fascinating thing. What an error we commit being unable to see this fascination! Or is the dog in error?

- We cannot have certainty because different human beings experience things differently. When do we encounter this? I encounter it when friends drink alcohol. I do not enjoy alcohol. Not only am I not supposed to have it (because of a specific medical condition), but it tastes like nasty poisonous motor oil to me, and yet I see my friends go into paroxysms of delight over the subtleties and complexities of drinks, and my civilization build entire buildings, institutions, customs and industries around this thing which my senses tell me is terrible. My senses and those of my friends differ. Clearly someone must be wrong, unless there is no right here? I also have a color blind housemate who cannot tell that Hello Kitty Hot Chocolate is bright pink, and struggles to play the game Set in mediocre lighting.

We cannot have certainty because our senses disagree with each other. If I want to know if something is good, I ask my senses. Yet sometimes they disagree with each other. My eyes tell me this artichoke is just made of smooth leaves, yet my touch tells me it is prickly. My eyes tell me a lobster is scary and dangerous, and yet my tongue says is delicious. My eyes tell me the molten glass in this glassblowing demo looks goopy and exciting and like a fascinating texture like putty which would be awesome to touch, and yet my touch tells me owwwwwwwwwww hot hot hot hot hot! My touch tells me this cat is delightful and fuzzy and yet my nose tells me I should not be near it because achooo!

We cannot have certainty because our senses disagree with each other. If I want to know if something is good, I ask my senses. Yet sometimes they disagree with each other. My eyes tell me this artichoke is just made of smooth leaves, yet my touch tells me it is prickly. My eyes tell me a lobster is scary and dangerous, and yet my tongue says is delicious. My eyes tell me the molten glass in this glassblowing demo looks goopy and exciting and like a fascinating texture like putty which would be awesome to touch, and yet my touch tells me owwwwwwwwwww hot hot hot hot hot! My touch tells me this cat is delightful and fuzzy and yet my nose tells me I should not be near it because achooo!- We cannot have certainty because sometimes the same things seem different and lead us to different judgments in different circumstances. I might enjoy a food for a long time but then get food poisoning from it and, after that, always be revolted when I smell it. I might feel warm at 70 degrees but then be sick and feel cold at 70 degrees. I might think Gatorade is nasty but then be dehydrated and think it tastes great because my body craves elecrolytes.

- We cannot have certainty because the same objects seem different from different perspectives. A mountain that looks like a face from one angle looks like a random jumble from another. A square tower seen from a distance seems round. A stick in water looks bent. The moon above a skyline looks much bigger than the buildings but we have no real sense from that of how enormously big it really is, and can only realize the latter using a lot of math, or a space shuttle.

- We cannot have certainty because we never see objects alone. Have you ever had one of those articles of clothing that looks purple in some light and blue in other light, so people argue over which it is? Because it looks one way next to one thing and another way next to another. Well, what does it look like really? We can never see anything alone, we always see it surrouneded by other objects including air. If the stick is distorted by water, is it not also distorted by air? By vacuum? By light? We do not see objects, only groups of objects.

- We cannot have certainty because things take multiple forms. Bronze is red, except when it turns green. Water is clear, unless it’s blue, or fluffy snow white. Squid ink is black, unless it’s diluted to form purple, or sepia. That molten glass is enticingly orange and squidgy. What do any of these things really look like?

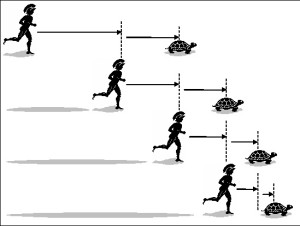

-

Illustrating types 6 & 8 doubt. Line segment AB is equal to line segment CD but looks longer. We cannot have certainty because we experience everything relative to other things. We cannot see a thing without making some judgment about things that are relative: this clementine is small, this stick is long, this lake is large. Small, long and large compared to what? Other objects of comparison intrude themselves into our analysis. The clementine is small compared to oranges, the stick long compared to other sticks, the lake large compared to my back yard. But we cannot judge things without judging them relative to others. To feed his fish for a while my father was growing Giant Amoebas. Giant Amoebas! Amoebas so big you could almost see them with the naked eye! They were huge! They were smaller than grains of sand and yet I thought they were huge!

- We cannot have certainty because we are biased by scarcity. I love this one, and I love its classic example. This is about how we judge things to be… well, frankly, how we judge them to be awesome or not. For example, comets are awesome. A little bright speck appears in the night that wasn’t there before, and flies across the heavens, really fast, so fast you can almost see it move! When there is a comet we get very excited. We discuss it, announce it, get out telescopes to look at it. In past ages people might pray to it, or read omens from it; now we photograph it and shoot probes at it. It’s super exciting: little bright speck in sky. Okay. So, every morning an enormous blinding ball of fire rises from the horizon, blotting out the night and transforming the entire sky to a wall of brilliant blue brightness streaked with rippling swaths of other beautiful colors, and it radiates down heat enough to transform our weather, burn our skin and feed countless life forms. It is, from any sense-perception objective sense, ten skillion times more exciting than a comet. But it’s just the sun, so, shrug. We are biased by scarcity. Two poems by Sappho and we all hear, but we find thousands of pages of unknown Renaissance poetry every year.

- We cannot have certainty because different peoples have different customs, habits, laws, beliefs and ethics, and are biased by them. I think you all know this one. Though it will take over a millennium for it to get to be so common, since cultural relitivism isn’t a broadly-discussed or accepted thing until the enlightenment when Montesquieu and Voltaire made themselves its champions. Skepticism has a long road ahead of it, from Pyrrho to the present. But for now, let’s sit back with Socrates and picnic on this raw form of classical, eudaimonist skepticism, challenging our science-loving, learning-loving, exploration-loving, post-enlightenment selves to test ourselves with the quesiton of whether it might be a safe and happy thing sometimes, in its own strange way, to not know. And we should also comfort Sartre a bit–he hadn’t heard, before today, about poor Pluto. (Descartes: “What’s Pluto?” Socrates: “Are you sure you want to know?”)

Continue this foray into the history of skepticism with Part II: Classical Hybrids.