How is Inventing the Renaissance an SFF-Related Work?

It’s a surprisingly fun question.

It’s a surprisingly fun question.

This year, the British Science Fiction Association Awards included my nonfiction history, Inventing the Renaissance: Myths of a Golden Age, on its long list of nominees for Best Non-Fiction (Long). Usually works in this category are directly about SFF: biographies of writers, histories of the field, edited scripts or illustration books, essays about the craft of writing SFF, works like (this year) Payton McCarty-Simas’s That Very Witch: Fear, Feminism, and the American Witch Film, or Joy Sanchez-Taylor’s Dispelling Fantasies: Authors of Colour Re-Imagine a Genre. Among these, my history of ideas of the Renaissance era and how they evolved from the 1400s to the current century, centered in tales of Machiavelli, Petrarch, and the Borgias, stands out like an old leather-bound tome among this year’s colorful Best Novel finalists.

Even I paused to ponder, “But is it related to SFF?”

The interesting part is not the yes, but that it is in so many very different ways.

The simplest way is that it is peppered with direct genre references. There are overt invocations of Batman, Tolkien, Assassin’s Creed, time machines, and Sherlock Holmes, subtler only-fans-would-spot-it references to works like Babylon 5 and Firefly, and analyses of magical moments in Shakespeare. Another is that it touches on the historical sources of modern fantasy. It also discusses, in little corners tucked among the major arguments, the histories of magical and supernatural beliefs in soul-projection, demon summoning, angelology, theurgy, Greek and Roman gods, angels that aren’t not the same thing as Roman gods, demonic possession, alchemy, the dowsing rod, and Diogenes’ Laertius’s claim that Pythagoras could fly around in a chariot of solar fire and zap people with a divine laser beam powered by his philosophical contemplation of the number ten. And, of course, it makes an only-slightly-facetious argument, well founded in the primary sources, that Pope Paul II was a vampire, and that that Pope Sixtus IV was possessed by a demon. (Who am I to doubt our most plausible period accounts?) But, fun as these are, they constitute no more than two percent of the book.

Another way—both more direct and less obvious—is that the main argument of the book is enormously important to both science fiction and fantasy as genres: that historians have agreed for decades that the Middle Ages weren’t a dark age nor the Renaissance a golden age, and that in fact the whole idea of dark and golden ages is a myth, but it’s such a narratively satisfying and politically useful myth that it persists and multiplies in fiction, journalism, propaganda, and popular imagination.

The politics part is that it is extremely persuasive if you can claim your candidate/party/ product will bring about a golden age and your rival/opponent/competitor is like the bad no good Dark Ages: to see this you have only to see how the economic history theory that the Renaissance was enabled by innovations in banking and finance was exaggerated during the Cold War into the extremely useful claim that capitalism caused the Renaissance and communism was like the bad no good Medieval world; that or (sigh) the persuasive power of the promise to make [whatever] “great again.”

The genre fiction part is in our world building. Innumerable world builds, both SF and fantastic, describe an excellent deep past, followed by a crisis or fall and then a dark age, either setting the tale in the moment that hopes to end that dark age, or in the new but fragile better age which could plunge back into it. Hari Seldon’s cycles of history, Tolkien’s high elven deep past, tales of the coming of dragons, the ending of magic, rebuilding after WWIII, everything post-apocalyptic, Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, Jemison’s Broken Earth series: all of these draw on the archetype of of the fall of Rome and an age of ash and shadow which came after—an archetype which is the protagonist of my history, invented in the late 1300s by Francesco Petrarch and Leonardo Bruni, whose evolution, popularity, impact, and ineradicability I trace over 550 years. In this sense, Inventing the Renaissance chronicles the birth of a major force in SFF just as much as other nominees, like D Harlan Wilson writing about Kubrick, or Henry Lien about the art of Eastern storytelling in his fabulous Spring, Summer, Asteroid, Bird.

But Inventing the Renaissance is related in another, completely separate way: I wrote it using techniques from SFF and gaming.

Inventing the Renaissance is a really weird work of historical nonfiction, one which makes historian friends and nonfiction history fans comment on how totally different it feels from most histories they’ve read. It’s been described as vivid, irreverent, peppy, bloggy, witty, provocative, energetic, and entertaining, with the Amazon blurb adding, “you would never expect a work of deep scholarship to make you alternately laugh and cry,” but you would expect exactly that if you realize what it really is: a history packed with the storytelling techniques of SFF.

The section most shaped by SFF is Part III (constituting about 1/3 of the book) which is composed of fifteen one-chapter mini-biographies of different Renaissance figures whose lives demonstrate different things about the period: a musician, a sculptor, an assassin, a woodcarver, a merchant matron, two princesses, three prophets (one male, two female), four Greek scholars (three male, one female), and our friend Machiavelli, their lives crisscrossing the continent and centuries that hosted this thing we call the Renaissance. I learned the power of switching point-of-view from studying SFF novels that do exactly that so powerfully, and thinking about it when choosing when to have my own work jump narrators. The power of having them crisscross and retell the same events from different points of view I learned from time loop fiction: the method of telling a story through once, then looping back and telling it again with slight changes, or from a different point of view. I encountered it first as kid watching old Doctor Who and the X-Men cartoon show version of Days of the Future Past, then in more sophisticated prose versions like Bester, Grimwood and Walton. And the especially potent twist as I switch from a cluster of lives all on one side of the conflict to suddenly show the POV of their adversary, switching for one very special chapter into the enormously powerful second person, comes from my experience writing character sheets for theatrical LARP, especially my the (in)famous papal election simulation, based in turn on LARPs I’ve played in myself (thanks especially to Warren Tusk of Paracelsus Games).

But storytelling tools I learned from SFF spill out beyond that section.

One is a technique I always think of is Meanwhile in Space…, named for those moments (particularly conspicuous in Gundam) where you’ve been following the characters in one arena for quite some time and then the next chapter or scene cuts to the space station where totally different people are doing something in parallel. In that spirit, my lovely tale of Renaissance histories is flowing along when we hit “And Now for a Tangent About Vikings,” and thereafter we occasionally cut away from my historians bickering about the Renaissance Studies to Meanwhile While Investigating Greenland…, in a way which eventually weaves back together to join the A-Plot exactly the way an SF reader knows the scenes on the space station someday must. The book is also woven through with fun but unnecessary Shakespeare references, which persistently pop up as examples of things or ways of expressing things, just as some fantasy narrators constantly bring in quotes from an in-world literary figure, as Dune quotes the works of Princess Irulan.

And, most radical for a nonfiction history yet least radical as an actual technique, Inventing the Renaissance has a first-person narrator: me.

I’m present in the text. It has sections titled “Why You Shouldn’t Believe Anyone (Including Me) About the Renaissance,” and “Why Did Ada Palmer Start Studying the Renaissance?” and “Are You Remembering Not To Believe Me?” It describes personal scenes, like walking over a bridge with an art historian friend who observed X, which made me realize Y. When citing scholars, I say, “my friend Name” or “my mentor Name” or “Name who, at a conference, once told me…” When treating past historians, I discuss what I read as a student and how it feels looking back on that. It’s in the conversational style of my blogging voice, and confesses sometimes that we don’t know whether A or B is true but I know I’m biased toward A.

Any history work could lift the veil and do this, but few do. In fact, shortly before I wrote the book, I submitted an article to Renaissance Quarterly in which, when commenting on an element of the historians’ practice, I used the phrase, “When we Renaissance historians do X…” and was told by the editor that the journal’s style guide forbids the use of the first person, whether singular or plural in any circumstance. It felt bizarre. First person is a vital tool of human honesty and humility. I wanted to say “We err when we do X,” not hover in condescending judgment behind the falsehood of, “They err when they do X.” It made me think about why we erase the first-person historian, which my fiction-reader, fiction-writer brain rebels against.

It’s so amazingly powerful having a first-person narrator, it adds so much, lets you accomplish so much as every sentence tells the reader, not just the facts in the sentence, but the nuances of seeing just how narrator put it: with warmth, with scorn, with expertise, with anxiety, with love. I’ve never planned out a fiction project and not had its first-person narrator be at the heart of the whole plan from the beginning (this applies to ten series, the four I wrote before Terra Ignota, TI itself, and the next five in the works). And, looking back, many of the histories that had struck me most when training as a historian had been those which let the speaker show, especially Peter Gay’s incredibly moving introduction to The Freud Reader, the warmth and presence of Don Cameron Allen in his Doubt’s Boundless Sea, and the first-person memoir-like early parts of Greenblatt’s The Swerve.

I don’t think every nonfiction history should make the historian visibly present in first-person, plenty do not need it and would not benefit from it. But since I was writing a history of histories, whose primary aim was to show the reader the historian’s craft, and the long continuity of historians inventing and reinventing the Renaissance from 1380 to today including me, it felt genuinely disingenuous to not make myself just as much an object of judgment for the reader as Petrarch, Bruni, Machiavelli, Burckhardt, Baron, Kristeller, Celenza, Hankins et al. And it reveals much more about that tradition when I say “my dissertation adviser Jim Hankins” or “my academic grandfather Kristeller,” or “my generous friend and mentor Chris Celenza” next to “Poggio’s mentor Petrarch.” The craft of history is, not turtles, but teachers all the way down.

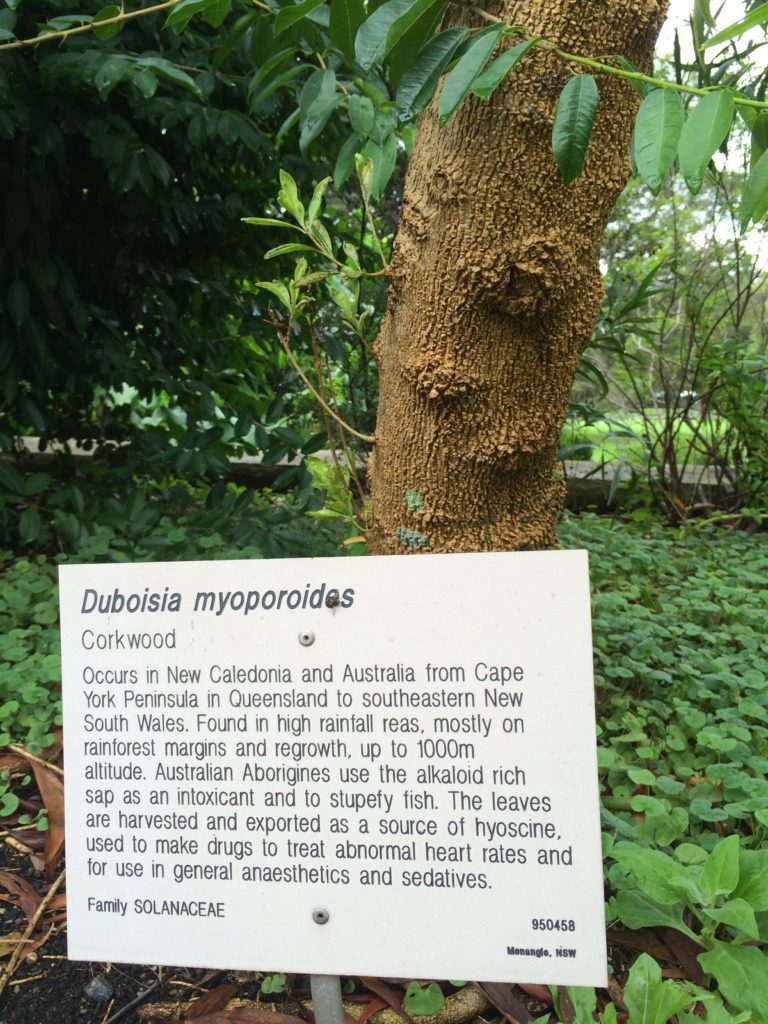

I also use the term History Lab for our collaborations, our conferences and conversations the place where we brew up new histories, as, down the hall, the molecular engineers brew up new pharmaceuticals.

Now, I won’t pretend that I actually thought through all this about first before I started writing Inventing the Renaissance. The book began as a blog post I rage-wrote as a stress vent during COVID summer 2020, and only when the blog post draft hit 40,000 words did I realize: oops, this is a book. But when time then came to polish it to be bookier, I thought about the first-person nature of my blogging, and how appropriate it was to take off my mask and reveal the historian in a book whose goal was to show how histories get made, and why we keep needing to replace old ones with new better ones, new theories of what and why the Renaissance was replacing each other, each better than the last, as (to use the comparison I use in the book) the Big Bang Theory will someday be replaced by some further refinement, the Better-Than-The-Big-Bang-Theory Theory. The chemist in a white lab coat is a familiar image, the archaeologist or paleontologist in dusty field kit, the historian… I had the chance to create that image in the reader’s mind, just as I do my first-person narrators when they’re not me. And I could make that image one of a curious and ever-changing mind surrounded by friends, colleagues, teachers, and students, all learning from each other in a long chain of still-discovering.

I was so delighted when the first reviews from historians commented on how the book presented historians who are generally seen as intellectual adversaries in debate and the fruitful and supportive value of those debates, and also at comments on how striking and unique it was for me to discuss my students as well as my mentors, the generations of knowledge at work. But thinking through generations and character relationships is part of what reading and writing SFF taught me to do.

We don’t tend to talk about academic history, or even history pop fiction, as genres, the way we do SF, and fantasy, and even historical fiction, but they are. The same way fusing SF + mystery or fantasy + epistolary novel can yield rich and exciting work, fusing nonfiction history with the techniques and approaches of SFF can do the same.

And, of course, there’s the question of what you’d say to Machiavelli if you had a time machine…

Below you’ll find some news, links to excerpts from Terra Ignota book 4, and a discussion of point-of-view in the craft of writing, but I’m posting today mainly to announce that I have an

Below you’ll find some news, links to excerpts from Terra Ignota book 4, and a discussion of point-of-view in the craft of writing, but I’m posting today mainly to announce that I have an

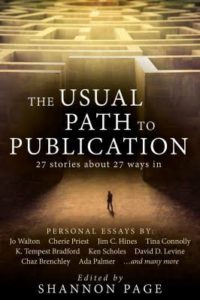

I want to share an essay today, one of the most personal things I’ve ever written, and one of those I’m proudest of. It’s about how I sold my first novel.

I want to share an essay today, one of the most personal things I’ve ever written, and one of those I’m proudest of. It’s about how I sold my first novel.