Sketches of a History of Skepticism Part 4: the Renaissance, Montaigne and a touch of Voltaire

(Best to begin with Part 1 and Part 2 of and Part 3 this series.)

Doubt in the Renaissance and Reformation

My own period I will treat the most briefly in this survey. This may seem like a strange choice, but I can either do a general overview, or get sidetracked discussing individual philosophers, theologians and commentators and their uses of skepticism for another five posts. So, in brief:

In the later Middle Ages, within the philosophical world, the breadth of disagreement within scholarship, how different the far extreme theories were on any given topic, was rather circumscribed. A good example of a really fractious fight is the question of, within your generally Aristotelian tripartite rational immortal soul, which of the two decision-making principles is more powerful, the Intellect or the Will? It’s a big and important question – without it we will starve to death like Buridan’s ass, and be unable to decide whether to send our second sons to Franciscan or a Dominican monasteries, plus we need it to understand how Original Sin, Grace and salvation work. But the breadth of answers is not that big, and the question itself presumes that everyone involved already believes 90% the same thing.

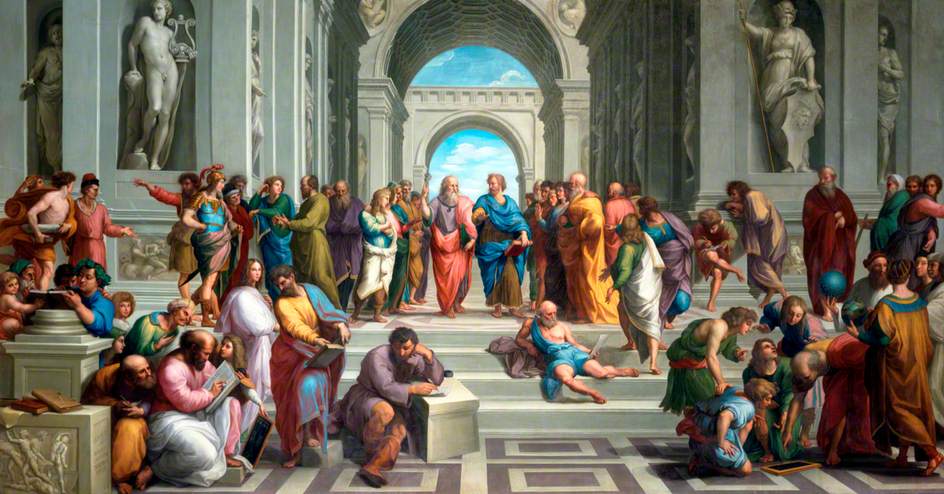

Enter Petrarch, “Let’s read the classics! They’ll make us great like the Romans!” Begin 250 years of working really hard to find, copy, correct, translate, edit, print and proliferate every syllable surviving from antiquity. Now we discover that Epicurus says there’s no afterlife and the universe is made of atoms; Stoics say the universe is one giant contiguous object without motion or individual existence; Plato says there’s reincarnation (What? The Plato we used to have didn’t say that!); and Aristotle totally doesn’t say what we thought he said, it turns out the Organon was a terrible translation (Sorry, Boethius, you did your best, and we love you, but it was a terrible translation.) Suddenly the palette of questions is much broader, and the degree to which people disagree has opened exponentially wider. If we were charting a solar system before, now we’re charting a galaxy. But the humanists still tried hard to make them all agree, much as the scholastics and Peter Abelard had, since the ancients were ALL wonderful and ALL brilliant and ALL right, right? Even the stuff that contradicts the other stuff? Hence Renaissance Syncretism, attempts by philosophers like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola to take all the authors of antiquity, and Aquinas and a few others in the mix, and show how they were all really saying the same thing, in a roundabout, hidden, glorious, elusive, poetic, we-can-make-like-Abelard-and-make-it-all-make-sense way.

Before you dismiss these syncretic experiments as silly, or as slavish toadying, there is a logic to it if you can zoom out from modern pluralistic thinking for a minute and look at what Renaissance intellectuals had to work with.

To follow their logic chain you must begin–as they did–by positing that Christianity is true, and there is a single monotheistic God who is the source of all goodness, virtue, and knowledge. Wisdom, being wise and good at judgment, helps you tell true from false and right from wrong, and what is true and right will always agree with and point toward God. Therefore all wise people in history have really been aiming toward the same thing–one truth, one source. Plato and Aristotle and their Criteria of Truth are in the background of this, Plato’s description of the Good which is one divine thing that all reasoning minds tend toward, and Aristotle’s idea that reasoning people (philosophers, scientists) working without error will come to identical conclusions even if they’re on opposite sides of the world, because the knowable categories (fish, equilateral triangle, good) are universal. Thus, as Plato and Aristotle say we use reason to gradually approach knowledge, all philosophers in history have been working toward the same thing, and differ only in the errors they make along the way. This is the logic, but they also have evidence, and here you have to remember that Renaissance scholars did not have our modern tools for evaluating chronology and influence. They looked at early Christian writings, and they looked at Plato and Aristotle, and they said, as we do, “Wow, Plato and Aristotle have a lot of ideas in common with these early Christians!” but while we conclude, “Early Christians sure were influenced by Plato and Aristotle,” they instead concluded, “This proves that Plato and Aristotle were aiming toward the same things as Christianity!” And they had further evidence from how tangled their chronologies were. There were certain key texts like the Chaldean Oracles which they thought were much much older than we now think they are, which made it look like ideas we attribute to Plato had independently existed well before Plato. They looked at Plotinus and other late antique Neoplatonists who mixed Plato and Aristotle but claimed the Aristotelian bits were really hidden inside Plato the whole time, and they concluded, “See, Plato and Aristotle were basically saying the same thing!” Similarly confusing were the works of the figure we now call Pseudo-Dionysius, who we think was a late antique Neoplatonist voicing a mature hybrid of Platonism and Aristotelianism with some Stoicism mixed in, but who Renaissance scholars believed was a disciple of Saint Paul, leading them to conclude that Saint Paul believed a lot of this stuff, and making it seem even more like Plato, Aristotle, Stoics, ancient mystics, and Christianity were all aiming at one thing. So any small differences are errors along the way, or resolvable with “sic et non.”

The problem came when they translated more and more texts, and found more contradictions than they could really handle. Ideas much wilder and more out there than they expected suddenly had authoritative possibly-sort-of-proto-Christian authors endorsing them. Settled questions were unsettled again, sleeping dragons woken. For example, it wasn’t until the Fifth Lateran Council in 1513 that the Church officially made belief in the immortality of the soul a required doctrine for all Christians, which does not mean that lots of Christians before 1513 didn’t believe in the afterlife, but that Christians in 1513 were anxious about belief in the afterlife, feeling that it and many other doctrines were suddenly in doubt which had stood un-threatened throughout the Middle Ages. The intellectual landscape was suddenly bigger and stranger.

Remember how I said Cicero would be back? All these humanists read Cicero constantly, including the philosophical dialogs with his approach of presenting different classical sects in dialog, all equally plausible but incompatible, leading to… skepticism. And as they explored those same sects more and more broadly, Cicero the skeptic became something of the wedge that started to expand the crack, not overtly stating “Hey, guys, these people don’t agree!” but certainly pressing the idea that they don’t agree, in ways which humanists had more and more trouble ignoring as more texts came back.

Aaaaaand the Reformation made this more extreme, a lot more extreme, by (A) generating an enormous new mass of theological claims made by contradictory parties, adding another arm to our galactic spiral, and (B) developing huge numbers of fierce and damning counter-arguments to all these claims, which in turn meant developing new tools for countering and eroding belief. Thus, as we reach the 1570s, the world of philosophy is a lot bigger, a lot deadlier (as the Reformation and Counter-Reformation killed many more people for their ideas than the Middle Ages did), and a lot scarier, with vast swarms of arguments and counter-arguments, many of them powerful, persuasive, beautifully reasoned, and completely incompatible. And when you make a beautiful yes-and-no attempt to make Plato and Epicurus agree, you don’t have the men themselves on hand to say “Excuse me, in fact, we don’t agree.” But you did have real live Reformation and Counter-Reformation theologians running around responding to each other in real time, that makes syncretic reconciliation the more impossible.

Remember how Abelard, who able to make St. Jerome and St. Augustine seem to agree, drew followers like Woodstock? Well, now his successors–Scholastic and Humanist, since the Humanists were all ALSO reading Scholasticism all the time–have a thousand times as many authorities to reconcile. You think Jerome and Augustine is hard? Try Calvin and Epicurus! St. Dominic and Zwingli! Thomas Aquinas is a saint now, let’s see if you can Yes-and-No the entire Summa Theologica into agreeing with Epictetus, Pseudo-Dionysius and the Council of Trent at the same time! And remember, in the middle of all this, that most if not all of our Renaissance protagonists still believe in Hell and damnation (or at least something similar to it), and that if you’re wrong you burn in Hellfire forever and ever and ever and so do all your students and it’s your fault. Result: FEAR. And its companion, freethought. Contrary to what we might assume, this is not a case where fear stifled inquiry, but where it stimulated more, firing Renaissance thinkers with the burning need to have a solution to all these contradictions, some way to sort out the safe path amid a thousand pits of Hellfire. New syntheses were proposed, new taxonomies of positions and heresies outlined, and old beliefs reexamined and refined or reaffirmed. And this period of intellectual broadening and competition brought with it an increasing inability to believe that any one of these options is the only right way when there are so many, and they are so good at tearing each other down.

And in the middle of this, experimental and observational science is advancing rapidly, and causing more doubt. We discover new continents that don’t fit in a T-O map (Ptolemy is wrong), new plants that don’t fit existing plant taxonomy (Theophrastus is wrong), details about Animals which don’t match Aristotle (we’d better hope he’s not wrong!), the circulation of the blood which turns the four humors theory on its head (Not Galen! We really needed him!), and magnification lets us finally see the complexity of a flea, and realize there is a whole unexplored micro-universe of detail too small for the naked eye to experience, raising the question “If God made the Earth for humans, why did God bother to make things humans can’t even perceive?”

Youth: “But, Socrates, why did experimental and observational science advance in that period? Discovering new stuff that isn’t in the classics doesn’t have anything to do with reconstructing antiquity, or with the Reformation, does it?”

Good question. A long answer would be a book, but I can make a quick stab at a short one. I would point at several factors. First, after 1300, and increasingly as we approach 1600, European rulers began competing in new ways, many of them cultural. As more and more nobles were convinced by the humanist claim that true nobility and power came from the lost arts of the ancients, so scholarship and unique knowledge, including knowledge of ancient sciences, became mandatory ornaments of court, and politically valuable as ways of advertising a ruler’s wealth and power. Monarchs and newly-risen families who had seized power through war or bribery could add a veneer of nobility by surrounding themselves with libraries, scholars, poets, and scientists, who studied the ancient scientific sources of Greece and Rome but, in order to understand them more fully, also studied newer sources coming from the Middle East, and did new experiments of their own. A new astronomical model of the heavens proclaimed the power of the patron who had paid for it, just as much as a fur-lined cloak or a diamond-studded scepter.

Add to this the increase of the scales of wars caused by increased wealth which could raise larger armies, generating a situation in which new tools for warfare, and especially fortress construction, were increasingly in demand (when you read Leonardo’s discussions of his abilities, more than 75% of the inventions he mentions are tools of war). Add to that the printing press which makes it possible for novelties–whether a rediscovered manuscript or a newly-discovered muscle–to spread exponentially faster, and which makes books much more affordable, so that if only one person in 50,000 could afford a library before now it is one in 5,000, and even merchants could afford a few texts. Education was easier, and educated men were in demand at courts eager to fill themselves with scholars, and advertise their greatness with discoveries.

These are the main facilitators, but I would also cite another fundamental shift. I have talked before about Petrarch, and the humanist project to improve the world by reconstructing a lost golden age. This is the first philosophical movement since ancient stoicism that has had anything to do with the world, since medieval theology’s (perfectly rational in context!) desire to study the Eternal instead of the ephemeral meant that most scholars for many centuries had considered natural philosophy, the study of impermanent natural phenomena, as useless as studying the bathwater instead of the baby. Humanism generated a lot of arguments about why Earth and earthly things were worth more than nothing, even if they agreed Heaven and eternal things were more important, and I think the mindset which said it was a pious and worthwhile thing to translate Livy or write a treatise on good government contributed to the mindset which said it was a pious and worthwhile thing to measure mountains or write a treatise on metallurgy. Thought turned, just a little bit, toward Earth.

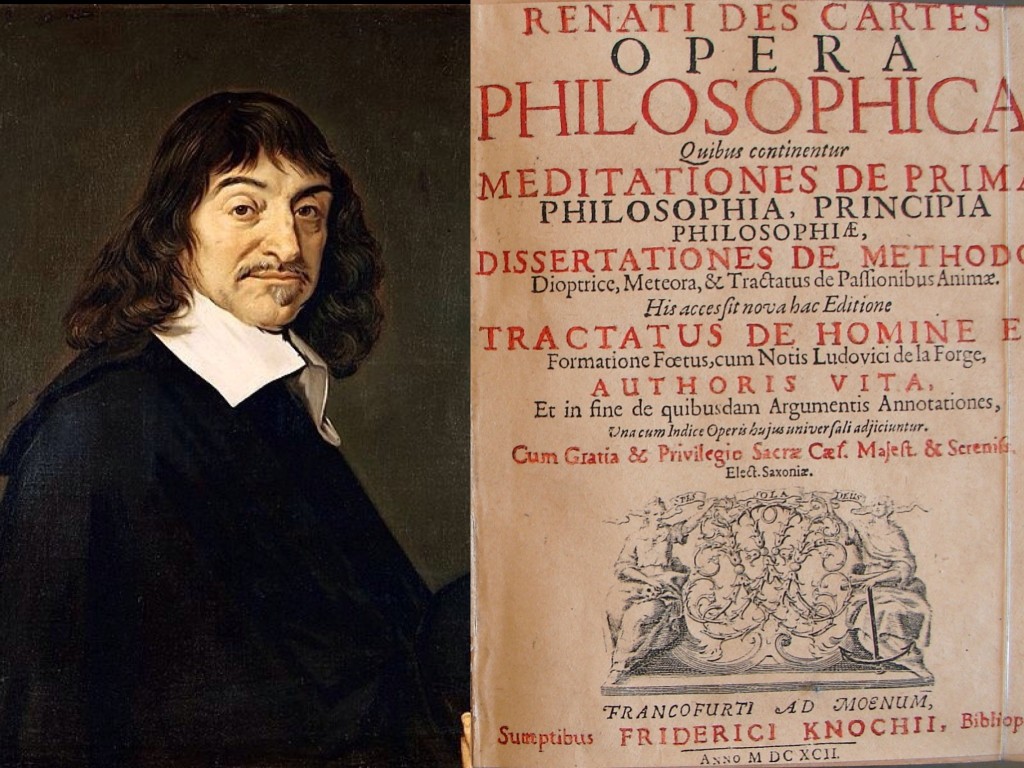

There, that’s the Renaissance and Reformation, oversimplified by necessity, but Descartes is chomping at the bit for what comes next. For those who want more, I shall do the crass thing here and say: for more detail, see my book Reading Lucretius in the Renaissance, or Popkin’s History of Skepticism, or wait.

At last, Montaigne!

At last, Montaigne!

Like the world which basked in his writings, and shuddered in his “crisis,” I love Montaigne. I love his sentences, his storytelling, his sincerity, his quips, his authorial voice. Reading Montaigne is like like slowly enjoying a glass of whatever complex, rich and subtle beverage you most enjoy a glass of (wine for many, fresh goat milk for me!). Especially because, at the end, your glass is empty. (I see a contented Descartes nodding). When I set about starting to write this series, getting to Montaigne was, in fact, my secret end goal, since, if there is a founder of modern skepticism, it is Michel Eyquem de Montaigne.

Montaigne was unique, an experiment, the natural experiment to follow at the maturation of the Renaissance classical project but still, a unique child, raised as an overt pedagogical experiment outlined by his father: Montaigne grew up speaking only Latin. He was exposed to French in his first three years by country nurses, but from three on he was only allowed contact with people–his tutor, parents and servants–speaking Latin. He was a literal attempt to raise a Cicero or Caesar, formed exclusively by classical ideas, the ideal man that the humanists had been hoping to create. Greek was later added, not with textbooks and the rod as was usual in those days but with games and music, and studies were always made to seem pleasant and wonderful by surrounding him with music (even waking the child every morning with delightful live music). He grew up to be about as perfect a Platonic Philosopher King as one could hope to imagine, studying law and entering politics, as his father wished, achieving the highest honors, but preferring life alone in his library, and frequently retiring to do just that, only to be dragged back into politics actually by popular demand of people who would come bang on his library door demanding that he come out to take up office and rule them. I think often about what it must have been like to be Montaigne, to be so immersed, enjoy these things so much, and only later discover that he was alone in a world with literally no other native speaker of his language. It must have been as difficult as it was wonderful to be Montaigne. But I think I understand why, when he lost his best friend Étienne de la Boétie, Montaigne wrote of his grief, his loss, the pain of solitude, with an intensity rarely approached in the history of human literature. He also wrote Essais, meandering writings, the source of the modern word “essay”, for which every schoolchild has the right to playfully curse him.

I will now go about explaining why Montaigne was so wonderful by describing Voltaire. Yes, it is an odd way to go about it, but the Voltaire example is clearer and more concise than any Montaigne example I have on hand, and, in this, Voltaire was a student of Montaigne, and Montaigne will only smile to see such a beautiful development of his art, as Bacon smiles on Newton, and Socrates on all of us.

I will now go about explaining why Montaigne was so wonderful by describing Voltaire. Yes, it is an odd way to go about it, but the Voltaire example is clearer and more concise than any Montaigne example I have on hand, and, in this, Voltaire was a student of Montaigne, and Montaigne will only smile to see such a beautiful development of his art, as Bacon smiles on Newton, and Socrates on all of us.

At the beginning of this sequence, I outlined two potential sources of knowledge: either (A) Sense Perception i.e. Evidence, or (B) Logic/Reason. The classical skeptics were born when the reliability these two sources of knowledge were drawn into doubt, Sense Perception by the stick in water, Logic by Xeno’s Paradoxes of Motion. Responses included the skeptics’ conclusion “We can’t know anything if we can’t trust Reason or the Senses,” and the various other classical schools’ Criteria of Truth (Plato’s Ideas, Aristotle’s Categories, Epicurus’s weak empiricism, etc.) All refutations we have seen along our long path have been based on undermining one of these types of knowledge sources: so when Duns Scotus fights with Aquinas, he picks on his logic, and when Ockham fights with him he, often, picks on his material sensory evidence. (“Where is the phantasm? Huh? Huh?”)

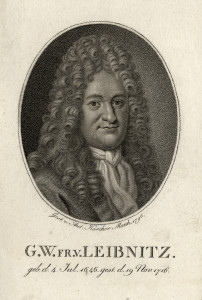

Everybody, I’d like to introduce you to Leibniz. Leibniz, this is everybody. “Hello!” says Leibniz, “Very nice to meet you all.” We are going to viciously murder Leibniz in about three minutes. “It’s no trouble,” says Leibniz, “I’m quite used to it.” Thank you, Leibniz, we appreciate it.

Everybody, I’d like to introduce you to Leibniz. Leibniz, this is everybody. “Hello!” says Leibniz, “Very nice to meet you all.” We are going to viciously murder Leibniz in about three minutes. “It’s no trouble,” says Leibniz, “I’m quite used to it.” Thank you, Leibniz, we appreciate it.

Leibniz here made many great contributions to philosophy and mathematics, but one particular one was extraordinarily popular, I would go so far as to say faddy, a fad argument which swept Europe in the first half of the 18th century. You have almost certainly heard it before in mocking form, but I will do my best to be fair as we line up our target in our sites:

- God is Omnipotent, Omniscient and Omnbenevolent. (Given.) “Grrrr,” quoth Socrates.

- Given that God is Omniscient, He knows what the best of all possible worlds is.

- Given that God is Omnipotent, He can create the best of all possible worlds.

- Given that God is Omnibenevolent, He wants to create the best of all possible worlds.

- Any world such a God would make must logically be the best of all possible worlds

- This is the best of all possible worlds.

Now, this was a proof written, just like Anselm’s and Aquinas’s, by a philosopher expecting a readership who all believe, both in God, and in Providence. It is a comfortable proof of the logical certainty that there is Providence, that this universe is perfect (as the Stoics first theorized), and anything in it that seems to be bad or evil must, in fact, be part of a greater long-term good that we fail to see because of our limited human perspective. The proof made a huge number of people delighted to have such an elegant and simple argument for something they enthusiastically believed.

But, the proof also the side-effect that arguments about Providence often do, of making people start to try to reason out what the good was behind hidden evils. “Oh, that guy was struck with disease because he did X bad thing.” “Wolves exist to make us live in villages.” “That plague happened because those people were bad.” It was (much like Medieval proofs of the existence of God) a way philosophers could show off their cleverness to an appreciative audience, make themselves known, and put forward theories about right and wrong and what God might want.

In 1755 an enormous earthquake struck the great port city of Lisbon (Portugal), wiping out tens of thousands of people (some estimate up to 100,000) and leveling one of the great gems of European civilization. It remains to this day one of the deadliest earthquakes in recorded history, and many parts of Lisbon are still in ruins almost 300 years later. The shock and horror, to a progressive, optimistic Europe, was stunning. And immediately thereafter, fans of Leibniz started publishing essays about how it was GOOD that this had happened, because of XYZ reason. For example, one argument was that they were persecuting people for their religion, and this was God saying he disapproved <= REAL argument. (Note: Leibniz himself is innocent of all this, having died years before the earthquake – we are speaking of his followers.) Others argued that it was a bad minor effect of God’s general laws, that the physical rules of the Earth which make everything wonderful for humankind also make earthquakes sometimes happen, but that the suffering they cause is negligible against the greater goods that Providence achieves. And if one person in Europe could not stand these noxious, juvenile, pompous, inhumane, self-serving, condescending, boastful, heartless, self-congratulatory responses to unprecedented human suffering, that person was the one pen mightier than any sword, Voltaire.

Would words like these to peace of mind restore

The natives sad of that disastrous shore?

Grieve not, that others’ bliss may overflow,

Your sumptuous palaces are laid thus low;

Your toppled towers shall other hands rebuild;

With multitudes your walls one day be filled;

Your ruin on the North shall wealth bestow,

For general good from partial ills must flow;

You seem as abject to the sovereign power,

As worms which shall your carcasses devour.

No comfort could such shocking words impart,

But deeper wound the sad, afflicted heart.

When I lament my present wretched state,

Allege not the unchanging laws of fate;

Urge not the links of the eternal chain,

’Tis false philosophy and wisdom vain.

The God who holds the chain can’t be enchained;

By His blest Will are all events ordained:

He’s Just, nor easily to wrath gives way,

Why suffer we beneath so mild a sway:

This is the fatal knot you should untie,

Our evils do you cure when you deny?

Men ever strove into the source to pry,

Of evil, whose existence you deny.

If he whose hand the elements can wield,

To the winds’ force makes rocky mountains yield;

If thunder lays oaks level with the plain,

From the bolts’ strokes they never suffer pain.

But I can feel, my heart oppressed demands

Aid of that God who formed me with His hands.

Sons of the God supreme to suffer all

Fated alike; we on our Father call.

No vessel of the potter asks, we know,

Why it was made so brittle, vile, and low?

Vessels of speech as well as thought are void;

The urn this moment formed and that destroyed,

The potter never could with sense inspire,

Devoid of thought it nothing can desire.

The moralist still obstinate replies,

Others’ enjoyments from your woes arise,

To numerous insects shall my corpse give birth,

When once it mixes with its mother earth:

Small comfort ’tis that when Death’s ruthless power

Closes my life, worms shall my flesh devour.

This (in the William F. Fleming translation) is an excerpt from the middle of Voltaire’s Poem on the Lisbon Earthquake, which I heartily encourage you to read in its entirety. The poem summarizes the arguments of Camp Leibniz , and juxtaposes them with heart-wrenching descriptions of the sufferings of the victims, and with Voltaire’s own earnest and passionate expression of exactly why these kinds of arguments about Providence are so difficult to choke down when one is really on the ground suffering and feeling. The human is not a senseless pottery vessel, it is a thinking thing, it feels pain, it asks questions, it feels the special kind of pain that unanswered questions cause, the same pain the skeptics have been trying to help us escape for 3,000 years. But we don’t escape, and the poem captures it. The poem swept across Europe like a firestorm. People read it, people felt it, people recognized in Voltaire’s words the cries of anger in their own hearts. And they agreed. He won. The Leibniz fad ended. An entire continent-wide philosophical movement, slain.

And he used neither Logic nor Evidence.

And he used neither Logic nor Evidence.

Did you feel it? The poem persuaded, attacked, undermined, eroded away the respectability of Leibniz, but it did it without using EITHER of the two pillars of argument. There was no chain of reasoning. And there was no empirical observation. You could say there was some logic in the way he juxtaposed claims “God is a kind Maker” with counter-claims “I am not a potter’s jar, I am a thinking thing! I need more!”. You could say there was some empiricism or evidence-based argument in his descriptions of things he saw, or things he felt, since feelings too are sense-perceptions in a way, so reporting how one feels is reporting a sensory fact. But there was nothing in this so rigorous or so real that any of our ancient skeptics would recognize it as the empiricism they were attacking. Those people Voltaire describes – he did not see them, he just imagines them, reaching across the breadth of Europe with the strength of empathy. That potter’s wheel is a metaphor, not a syllogism. Voltaire has used a third thing, neither Reason nor Evidence, as a tool of skepticism.

What do we name this Third Thing? I have heard people propose “common sense” but that’s a terribly vexed term, going back to Cicero at least, which has been used by this point to mean 100 things that are not this thing, so even if you could also call this thing “common sense” it would just create confusion (we don’t need Aristotle looming with a lecture on the dangers of unclear vocabulary). I have heard people propose “sentiment” and I like how galling it feels to try to suggest that “sentiment” should enjoy coequal respect and power with Reason and Evidence, but it isn’t quite that either. I am not yet happy with any name for this Third Thing, and am playing around with many. All I will say is that it is real, it is powerful, it is as effective at persuading one to believe or disbelieve as Reason and Evidence are. And, even if there were shadows of this Third Thing earlier in human history, Montaigne was the smith who sharpened the blade and handed it to Voltaire, and to the rest of us.

Montaigne’s Essais are lovely, meandering, personal, structure-less, rambling musings in which topics flow one upon another, he summarizes an argument made for or against some heresy, then, rather than voicing an opinion, tells you a story about his grandmother that one time, or retells a bit of one of Virgil’s pastorals, or an anecdote about some now-obscure general, and then flows on to a different topic, never stating his opinion on the first but having shaped your thinking, through his meanders, until you feel an answer, a belief or, more often, disbelief, even if he never voiced one. And then he keeps going, taking up another argument, making it feel silly with an allegory about two bakers, another and–have you heard the news from Spain?–another, and another, and oh, the loves of Alexander, another, and another. And as it flows along you get to know him, feel you’re having a conversation with him, and somewhere toward the end you no longer believe any of the philosophical arguments he has just summarized are plausible at all, but he never once argued directly against any of them. It is a little bit like our skeptical Cicero, juxtaposing opposing views and leaving us convinced by none, but it is one level less structured, not actually a dialog with arguments and refutations. Skepticism, without Reason, without Evidence, just with the human honesty that is Montaigne, his doubts, his friendship, his communication to you, dear reader, across the barrier of page, and time, and language, this strange French-Roman, this only native Latin speaker born in a millennium, this alien, has made you realize all the philosophical convictions, everything in that broad spectrum that scholasticism plus the Renaissance plus the Reformation and Counter-Reformation ferocity have laid before you, none of it is what a person really feels deep down inside, not Montaigne, and not you. And so he leaves you a skeptic, in a completely different way from how the ancient skeptics did it, not with theses, or exercises, or lists, or counterarguments, just with… humanity?

Montaigne did it. His contemporaries found it… odd at first, a bit self-centered, this autobiographical meandering, but it was so beautiful, so entrancing, so powerful. It reared a new generation, armed with Reason and Evidence and This Third Thing, and deeply skeptical. Students at universities started raising their hands in class to ask the teachers to prove the school existed. Theologians advising princes started saying maybe it didn’t matter that much what the difference was between the different Christian faiths if they were close enough. A new age of philosophy was born, not a new school, but a new tool for dogmatism’s ancient symbiotic antagonist: doubt.

And, where doubt grows stronger and richer, so does dogmatic philosophy, having that much more to test itself against. Just as, in antiquity, so many amazing schools and ideas were born from trying to respond to Zeno and the Stick in Water, so Montaigne’s new tools of Skepticism, his revival and embellishment of skepticism, the birth, as we call it, of Modern Skepticism, was also the final ingredient necessary for an explosion of new ideas, new schools, new universes described by new philosophers trying to build systems which can stand up against a new skepticism armed, not just against Reason and Evidence, but with That Third Thing.

Thus, as 1600 approaches, the breakneck proliferation of new ideas and factions make Montaigne’s skepticism so popular that students in scholastic and Jesuit schools are starting to raise their hands and demand that the professor prove the existence of the classroom before expecting them to attend class. A “skeptical crisis” takes center stage in Europe’s great intellectual conversation, and multiplying doubt seems to have all the traditional Criteria of Truth in flight. It is onto this stage that Descartes will step, and craft, alongside his contemporaries, the first new systems which will have to cope, not with two avenues of attacking certainty, but, thanks to Montaigne, three. And will fight back against them with Montaigne’s arts as well. Next time.

Thus, as 1600 approaches, the breakneck proliferation of new ideas and factions make Montaigne’s skepticism so popular that students in scholastic and Jesuit schools are starting to raise their hands and demand that the professor prove the existence of the classroom before expecting them to attend class. A “skeptical crisis” takes center stage in Europe’s great intellectual conversation, and multiplying doubt seems to have all the traditional Criteria of Truth in flight. It is onto this stage that Descartes will step, and craft, alongside his contemporaries, the first new systems which will have to cope, not with two avenues of attacking certainty, but, thanks to Montaigne, three. And will fight back against them with Montaigne’s arts as well. Next time.

For now, I will leave you with one more little snippet of the future: I lied to you, about a simple happy ending to Voltaire’s quarrel with Leibniz. Oh, Leibniz was quite dead, not just because the man himself had died but because no philosopher could take his argument seriously after the poem. Ever. Again. In fact, a few years ago I went to a talk at at a philosophy department in which a young scholar was taking on Leibniz’s Best of All Possible Worlds thesis, and picking it apart using beautiful logical argumentation, and at the end everyone applauded and congratulated him, but when the Q&A started the first Q was “Well, um, this was all quite fascinating, but, isn’t Leibniz, I mean, no one takes that argument seriously anymore…” But the young philosopher was correct to point out that, in fact, no one had ever actually directly refuted it with logic. No one saw the need. But if Voltaire’s victory over logical Leibniz was complete, Leibniz was not the most dangerous of foes. Voltaire had contemporaries, after all, armed with Montaigne’s Third Thing just as Voltaire was. Rousseau will fire back, sweet, endearing, maddening Rousseau, not in defense of Leibnitz, but against the poem which he sees as an attack on God. But this battle of two earnest and progressive deists must wait until we have brought about the brave new world that has such creatures in it. For that we need Descartes, Francis Bacon, grim Hobbes, John Locke, and the ambidextrous Bayle.