Rags to Riches Stories Fake & Real, or Always Look Up Everybody’s Mom!

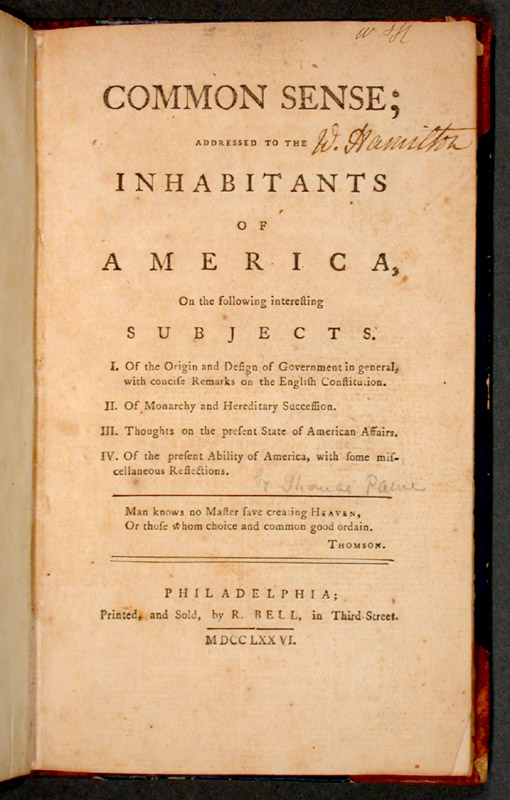

Rags to Riches stories were popular long before modern iterations like the “American Dream” or “self-made man”, or even early modern ones like Jack the Giant-Killer or Cinderella. And they were also always used as propaganda.

Rags to Riches stories were popular long before modern iterations like the “American Dream” or “self-made man”, or even early modern ones like Jack the Giant-Killer or Cinderella. And they were also always used as propaganda.

Looking back at two Rags to Riches tales of cardinals in the Renaissance, one fake one real, can show us the perennial tricks of seeming self-made for strategic purposes, and the afterlife that propaganda can have over decades and centuries.

Our fake case first; a myth which (like so many others) became a family myth once the first successful member used his new-gained power to launch a dynasty.

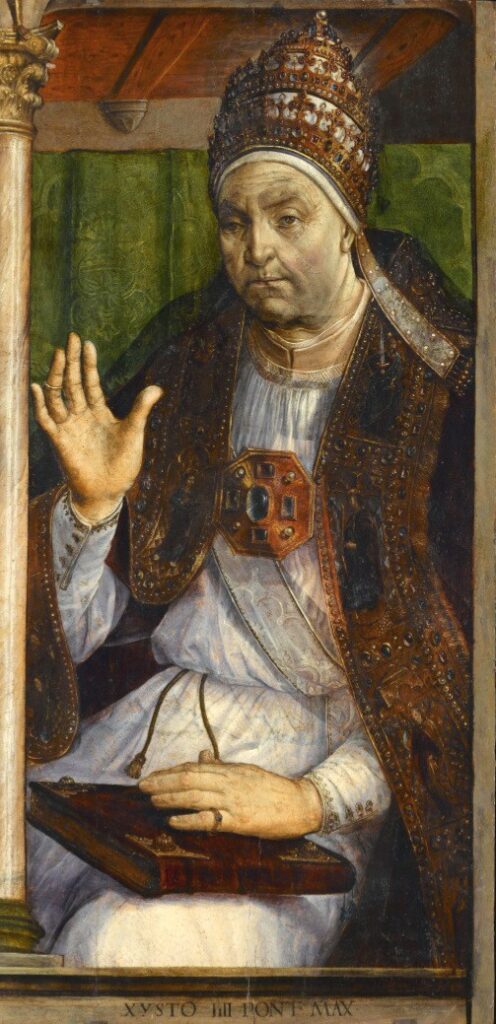

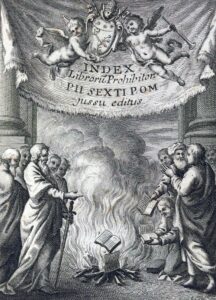

Francesco della Rovere (1414-1484) rose to the very highest rank a Renaissance man could, elected Pope Sixtus IV in 1471 at the age of 57. Ascending Saint Peter’s throne at such a comparatively young age meant he didn’t just have the honors of being pope but over a decade to use and entrench his power. When you look him up in encyclopedias, or look up his several nephews and grandnephews who became major powers after him like Giuliano della Rovere (1443-1513; elected pope 1503) and Raffaele Riario (1461-1521, cardinal as a teenager, nearly elected pope in 1513) you often see phrases like “born in poverty” or “rose from obscurity” or “from humble commoner stock.”

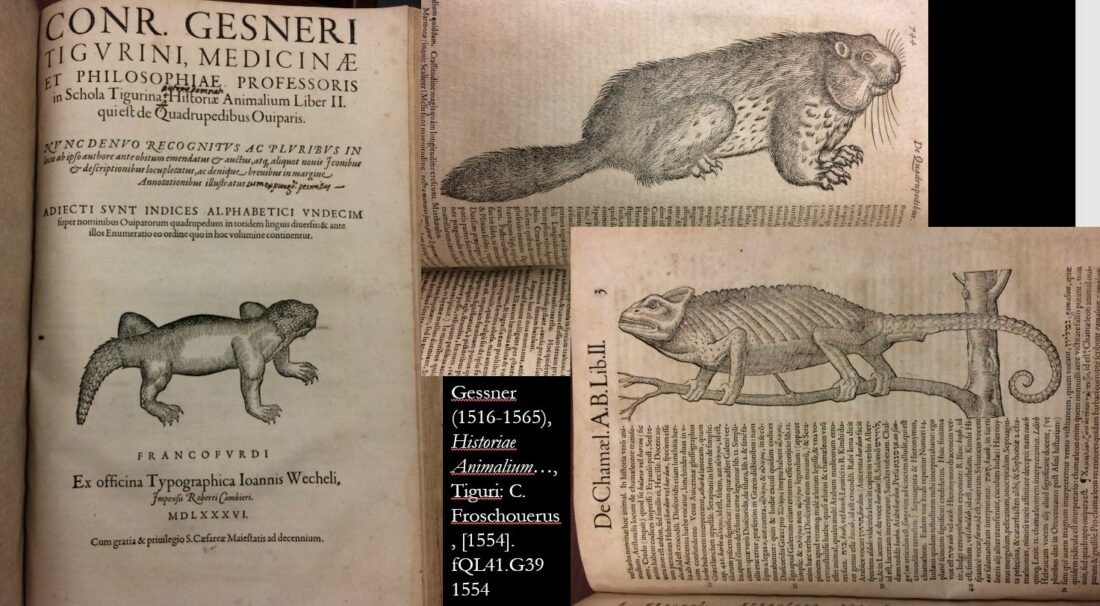

These phrases come from early (authorized by him and his heirs) biographies of Sixtus which stressed his commoner birth and rise from poverty because they plugged in perfectly to his career path, beginning as a Franciscan monk, and rising to be the head of the order. The Franciscans were the order most dedicated to poverty, often celebrated in paintings like this one of their founder Saint Francis literally marrying the Angel of Poverty. Saint Francis had absolutely refused to receive property or donations, even insisting on begging on the street for his supper when he was famous and a houseguest of wealthy benefactors, and to this day legally Franciscans own no property, everything they have technically belongs to the pope and is lent to them by him; if the pope sees a beggar when a Franciscan is walking by he can literally say “This poor man needs shoes, give him those shoes you’re wearing,” and the Franciscan is supposed to hand them over at once answering, “Of course, Your Holiness, they’re yours–thank you for lending them to me.” This aspect of the Franciscans is awesome, and makes us smile.

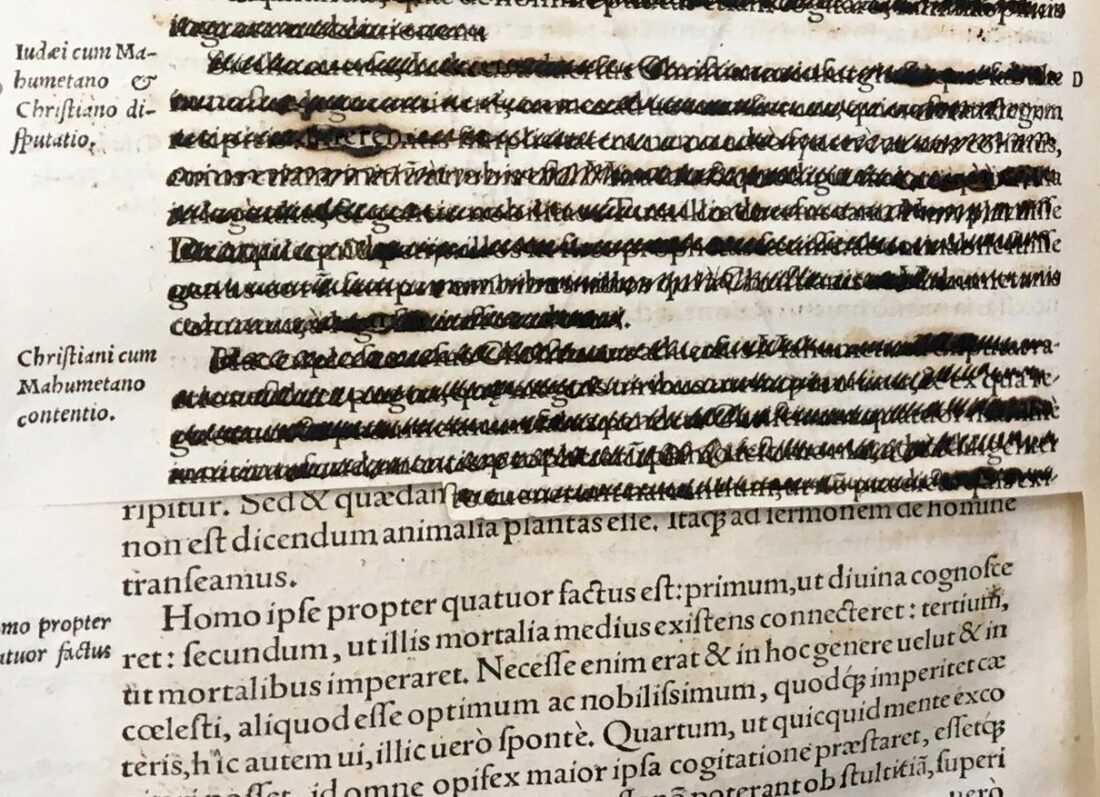

Sixtus rose to prominence as a theologian and scholar of philosophy, gaining fame lecturing at many Italian universities, and anecdotes of his early career talk of him refusing pay for his work, confirming his dedication to poverty. He was elected to head the Franciscan Order at age 50, made a cardinal three years later, so was an option in 1471 when the cardinals gathered (not yet in the Sistine which he would build) to elect a successor to the incredibly unpopular Pope Paul II.

Pope Paul came from one of the extremely old, extremely elite founding families of Venice (a fact vital to the plot), and had campaigned for the papacy with a platform that he would buy everyone who voted for him a palace in the Alps. He offended everyone in Rome by spurning the Vatican palace and insisting on spending a mountain of Church money building a giant Venetian style Palazzo for himself in the heart of Rome (if you’ve been through Piazza Venezia you’ve seen it), and spent his papacy being reclusive and antisocial, wandering his palace wearing his 10-million-dollar diamond-covered tiara around the house and cavorting with his many homosexual lovers. He is supposed to have died either while sodomizing a lover, eating a melon, or courageously attempting to sodomize a lover and eat a melon at the same time.

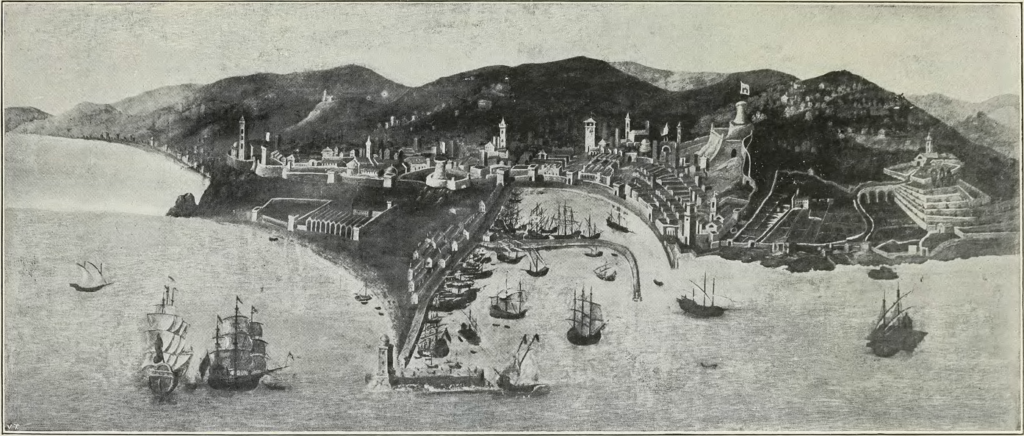

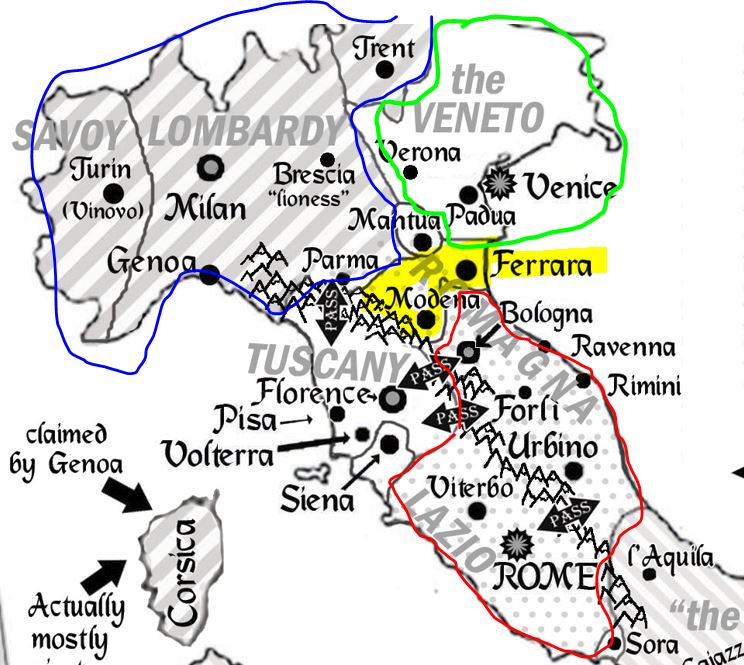

At Paul’s death, popular voices in Rome swore there would not be another Venetian pope for a thousand years! (a vow they’ve kept), and since Venice is the arch-enemy of Genoa, and Francesco della Rovere was born in Savona on the outskirts of Genoa, a selfless, philosophical, unworldly Franciscan poverty monk from a commoner family faithful to the enemy of Venice seemed like the perfect opposite. That Francesco, upon becoming pope, immediately dove into more nepotism, more graft, more entrenchment of family power, and more warmongering than Rome had seen in generations was a twist that jump-scared everyone. (If you know the Pazzi Conspiracy, this is that pope… yeah. The wild “Italian Wars” = these dudes.)

Now, since Sixtus rose to power on the charisma of Franciscan poverty, the propaganda cultivated by him and his heirs to legitimize their (extremely abrupt) power & sovereignty naturally dug deep into the rags-to-papal-riches myth, advertising Sixtus as the “son of a humble fisherman” invoking Christendom’s #1 fisherman Saint Peter, and biographers ever since have been eager to repeat this tale, so seeing commoner and fisherman elaborate that into 19th- and even 20th-century encyclopedia entries that say Sixtus was “born in poverty.”

Fact Check:

Francesco’s father Leonardo Beltramo di Savona della Rovere was indeed a commoner, in that he didn’t have any noble blood. But we must remind our eager biographers of a hundred years ago that, at the time, the Medici family were commoners too, and they were among the super-mega-rich banking families which made Florentine merchants the richest non-royals in Europe since Crassus of Rome.

Leonardo Beltramo della Rovere was not that rich, but he was powerful enough to be on Savona’s oligarchic city council and endow and decorate a family chapel in the city’s main church (something requiring multi-millionaire level wealth), and in his case “fisherman” actually meant he owned a fleet of fishing vessels, the capitalist owner of the means of production, not the man out on the boat with ropes and buckets. If Leonardo della Rovere was a fisherman then Cosimo de Medici was a bank clerk.

And following the rule that you should always look up everybody’s mom, Sixtus’s mother was Luchina Monteleoni, a fully noble-blooded daughter of an old and powerful noble family of Genoa, whose father had been exiled from the main city and settled in backwater Savona to bide his time and rebuild his fortune. Our commoner born in poverty turns out to actually be super rich commoner on dad’s side + temporarily semi-impoverished old family blood noble on mom’s, but propaganda let him exaggerate the halves of each side of his lineage that fit the Franciscan risen-from-nothing mythmaking.

And following the rule that you should always look up everybody’s mom, Sixtus’s mother was Luchina Monteleoni, a fully noble-blooded daughter of an old and powerful noble family of Genoa, whose father had been exiled from the main city and settled in backwater Savona to bide his time and rebuild his fortune. Our commoner born in poverty turns out to actually be super rich commoner on dad’s side + temporarily semi-impoverished old family blood noble on mom’s, but propaganda let him exaggerate the halves of each side of his lineage that fit the Franciscan risen-from-nothing mythmaking.

Sixtus isn’t Rags to Riches, he’s a son of the 1% climbing to join the 0.01%.

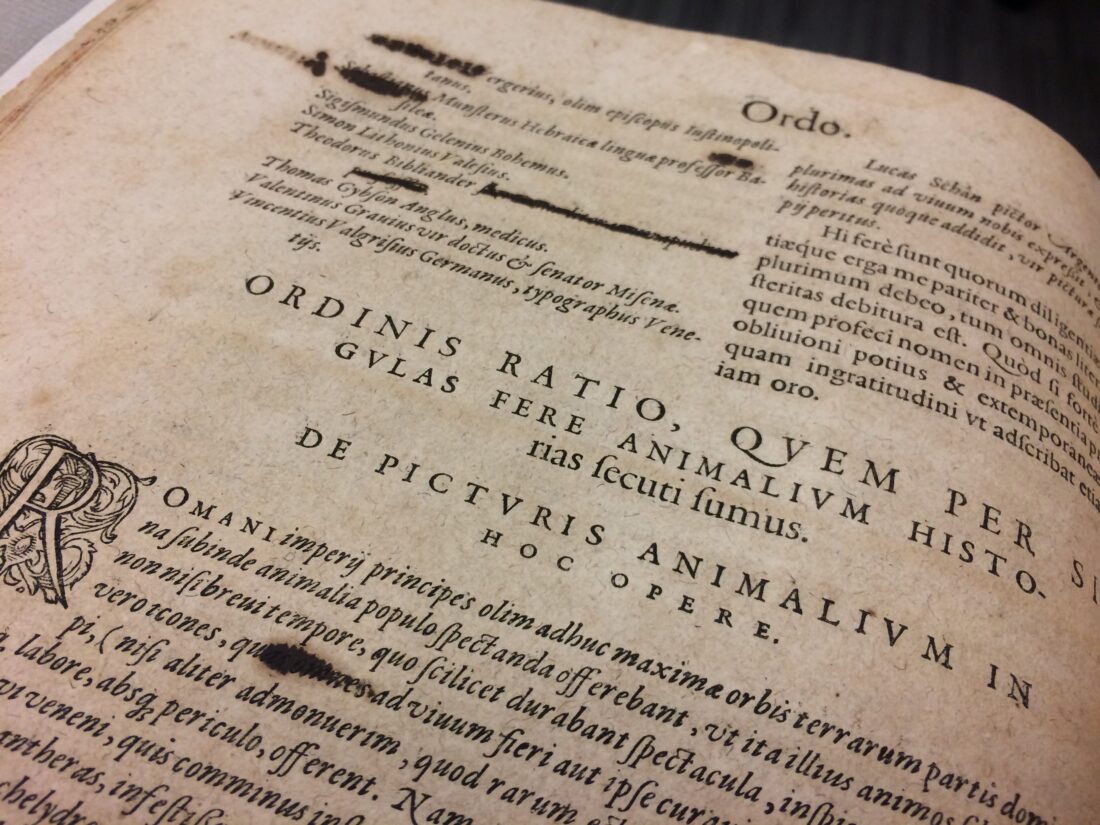

Digging deeper into the della Rovere propaganda, one thing Sixtus’s dad’s commoner status meant is that he didn’t have a coat of arms, something bishops and cardinals always need so they can hang it over their titular churches and put it on their stuff (even to this day they meet with armorial experts to create them). So Sixtus reached out to a totally unrelated noble family that happened to also be called della Rovere, a name meaning “of the oak” which isn’t too uncommon. These della Rovere were completely unrelated to Sixtus, and were Counts of Vinovo on the outskirts of Turin in Savoy, minor nobles in the sense that their power was local only so they weren’t someone a major duke would consider a marriage alliance with, but important enough within Savoy to have the hereditary honor of carrying one of the posts of the canopy over the Duke of Savoy at coronations and processions, and this is the patch when the Duke of Savoy was a brother-in-law or first-cousin of every neighboring king including France’s. As he started rising to power in Rome (this is before his papal days), Sixtus wrote to these della Rovere calling them “cousins” and proposing “reuniting” the family, and pitched a deal in which he got to use the Turin family’s coat of arms and in exchange two sons of the Vinovo della Rovere family came to him in Rome as his “nephews” and foster-sons, joining the many actual blood-nephews that he skyrocketed to major careers in the Church. Good deal for all.

While Sixtus was not yet Sixtus, still just a prominent Franciscan rising and jockeying for place in Rome, you find texts where he claims to be of the noble blood of the Counts of Vinovo, claiming fake nobility when he wanted to open the doors that nobility opens, while in other documents claiming poor commoner status in circumstances where that version of his backstory worked better. All this gave Sixtus the convenient chameleon ability to play the nobility card, the poverty card, and the commoner card in different hands.

(On Platina’s outfit contrasted with the others, see my post on Clarice Orsini’s Extremely Illegal Hat)

Sixtus’s most prominent nephew was Giuliano della Rovere (1443-1513), later Pope Julius II, a son of Sixtus’s younger brother Raffaello who married (always look up everybody’s mom!) a woman named Teodora Manirola. It’s really hard to find anything on her–even full-length biographies of Julius just include her name and move on–but even for a woman for whom we have only her name we can learn a lot from name + context, since Teodora Manirola = definitely Greek, something we can confirm with the few surviving docs about her father. A Greek woman with a wealthy, rising husband in Genoa (a major port city) and having her first child there in the 1440s pretty-much always means she’s emigree nobility from the Byzantine Empire, which at that point was being devoured from all sides by the conquests which would lead to Constantinople’s fall in 1453, and had reduced the once-vast empire to a few remnants. Those Greek-speaking Byzantine elites who were wealthy enough to do so to were rapidly relocating (with their more portable wealth) to other port cities like Genoa and Ancona, where their webs of contacts in coastal centers around the Mediterranean could be leveraged toward new wealth and power. Even branch members of the imperial Palaiologos family had settled in Genoa, so the ambitious rising brother of an ambitious rising cleric taking a Greek emigree wife in Genoa at that moment was a synthesis of ambition, wealth, trade contacts, and many paths to power.

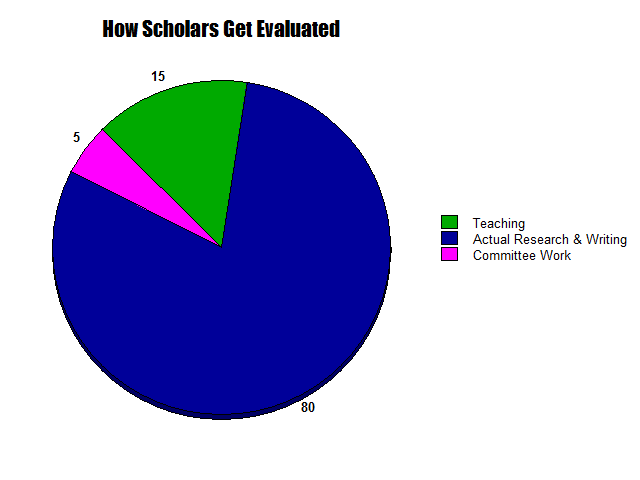

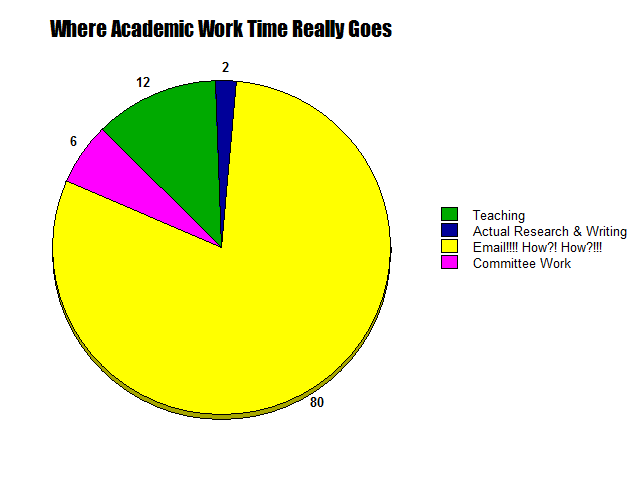

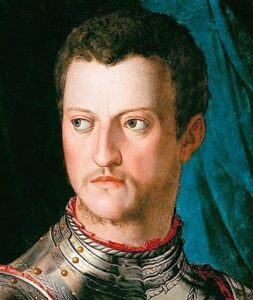

I’ve never seen any scholarship on Julius II discuss the fact that the man was half Greek, a fact which certainly affected the public identity and self-identity of the man known as the “Battle Pope” “Warrior Pope” or “Il Papa Terribile” i.e. Terrible in the sense of Ivan the Terrible (awesome, terrifying, warlord). Julius’s self-fashioning as an emperor and restorer of Rome’s military and imperial glory is constantly compared to propaganda of the Roman empire that fell in 475, but not the one that fell in 1453 when Julius was ten years old, so the grief and shock which hit his mother and Genoa’s Greek community (promptly flooded with arriving refugees) must have been one of his most formative childhood memories. Even biographies that speculate deeply about his thoughts and motives at different moments say nothing on this. Why? The same nineteenth-century biographers who formed the modern discipline of history that fell hook line and sinker for Sixtus’s “poor fisherman” propaganda did not look up people’s moms or think they had any influence, nor were the nationalist, race-purist, “history is about capturing the Spirit of a Nation!” historians of 1850 interested in mixed marriage (Italian + Greek) as a formative facet of the man who commissioned Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling.

Fact checking has left us aware how complex the layers of propaganda are when we look at the tomb shown below, a gorgeous one in Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, covered with crests of the della Rovere oak, built in one of Rome’s top churches (where princes of the Visconti-Sforza and noble lines are buried) for Cristoforo della Rovere (1434-78) one of the Vinovo della Rovere boys from Turin who were adopted by Sixtus in exchange for bringing their coat of arms and optional nobility as a propagandistic card Sixtus and his heirs could play.

Time for the tomb next door…

Buried one chapel over in the same church is our real Rags to Riches cardinal, Jorge da Costa of Portugal (1406-1508) the longest-lived cardinal in the history of the Church to this day, and the real Rags to Riches story to balance our propagandistic one… though not without his own propaganda.

Jorge was born in the tiny nothing village of Alpedrinha near… nothing really, but on the road east of Coimbra on a mountain pass where weary teams of muleteers hiked their weary way back-and-forth to the border with Castile. Jorge was one of fifteen children of Martim Vaz, himself one of these muleteers; the more aristocratic-sounding name “da Costa” which Jorge would later adopt came from the name of the farm where his hard-working father mucked out the donkey barns. His family is described in documents as dirt poor, and his father’s documented wife, the baker Catarina Gonçalves, was probably not Jorge’s mother who appears to have married him only later, so Jorge was either the product of a pre-marital fling or an earlier mother too obscure to leave even her name in the written record. While little is available on his parents, it’s worth noting that the prevalence of Moorish and north-African ancestry in Iberia’s poorest classes at this time means that da Costa was the only Roman cardinal in his century who may well have been a person of color, though the category is, of course, a modern one.

As a youth, Jorge ran away from home to better himself by becoming a swineherd, because swineherding was a step up! from the grueling world of mule caravans over the dangerous mountains, and was something he could do in a proper city, Santarém. He then went to Lisbon which had a university, to work as a servant and valet in a student hostel. This let him sneakily read his masters’ textbooks, and he managed to self-teach himself Latin, and started giving lessons as a Latin tutor. He started taking some classes with his profits, learning philosophy and theology, and when the hostel was bought out by a wealthy order of Augustinians, they gave him a chaplaincy in the monastery, a typical light-ish-work paycheck job of the kind those employed in the Church could gun for. Rags-to-middle-class-affluence achieved.

Da Costa’s next step came because he was a man who’d come from nothing. King Afonso V of Portugal wanted a personal chaplain and confessor, for himself and his sister Infanta Catarina, and when you’re a king and have to confess your sins, secrets, and fears to somebody, it’s ideal if that somebody is nobody, that is to say a man with no political ties, no allies, no powerful family, no allegiances, someone who can be the king’s man lifted from nothing and 100% dependent on and loyal to his royal patron. Recommended by the rich Augustinians he worked for, da Costa was the royal pick, a rare case of someone educated enough to fulfill the role of royal chaplain but risen from nothing so he could be fully the king’s man. As the king’s man he rapidly distinguished himself, and was trusted with diplomatic missions (time in Paris! bigtime!) and rewarded with high-paying benefices; donkey shed to Archbishop of Lisbon by age 58 is quite a rise! And when in 1476 the king managed to get our very same “poor fisherman” Pope Sixtus to give Portugal a cardinalship, he picked da Costa.

Da Costa used his royal favor and the wealth it brought to promote and employ many of his fifteen siblings, so by the time King Afonso died there were many titled da Costas and other da Costa bishops, and young da Costas born of marriages between his freshly-ennobled brothers and noble-blooded wives, and between his lavishly-dowered sisters and old blood noblemen.

Like many who are the King’s man, the death of the King halted the meteor. When Afonso’s son King João II climbed to the throne, he wanted to centralize power and renew Portugal, and succeeded enough that his reign is still called a “golden age” (a phrase which should always make our alarm bells go off). João did it by… banishing all the nobles and favorites who’d been powerful in his father’s day and seizing their lands and power, so the same royal favor which meant da Costa was in until age 77, meant he was out! out! out!, banished to Rome to serve as the king’s voice at the Vatican with the vague promise that if he served well enough he might someday hope for a recall home. His ousted and disgruntled siblings participating in a noble plot against King João’s life made the dynamic worse. So from 1482 to 1508, da Costa’s final career was as the top Portuguese diplomat in the Eternal City, power-brokering alongside the heirs of Sixtus, whose deeply-entrenched Italian roots of power and flexible ability to sometimes play the commoner poverty propaganda card and sometimes the old nobility card made them a major power, da Costa a minor ally who fell in to their faction.

Da Costa could’ve become pope in 1503 (he got the votes!) but declined the honor… as anyone with self-preservation streak would do in 1503 at the death of Alexander VI with his son Cesare Borgia’s armies occupying half of Italy as the Borgia vs. della Rovere faction deadlock held Rome in its grip of dual terrors; da Costa had seen how wretchedly the Cybo family did two elections earlier when Giovanni Battista Cibo had agreed to be the della Rovere’s compromise puppet pope, Innocent VIII, and time-savvied da Costa noped right out. (The Piccolomini cardinal who did agree to being the puppet pope in 1503 was from a family with much more respect and power in Italy, someone who had assets enough in Italy to act as a life preserver as he tried to tread water in those stormy seas). Instead he remained a cardinal, advancing Portugal’s interests and his own, and dying with wealth enough to plan a tomb which, at a glance, looks just alike in dignity and grandeur as the della Rovere tomb beside it.

What do we learn from our two Rags to Riches cases, fake and real?

One conclusion is that, both in 1450 and today, starting with wealth and powerful contacts puts you on the fast track, while truly rising through merit is slow, hard work. Da Costa was already 70 when he became a cardinal through this mix of merit + royal self-interest, while Sixtus had been only 53 when he got the red hat. Da Costa’s meteoric merit rise wasn’t meteoric, it took him many decades of hard work to catch up to where Sixtus’s wealth and noble contacts landed him as a teenager (employed by a wealthy monastery, first job in the Church), and if da Costa had died at the same age Sixtus did (70) he may well have breathed his last as the letter telling him that he’d received the scarlet was still on the boat en route from Rome. Da Costa’s ability to complete the rags-to-riches path required living 30 years longer than everybody else and working hard the whole time, and we may have seen a few other such rises if others on da Costa’s path shared the good fortune of living to 102! Managing to be pope in one’s 50s was not a door open to a real poor commoner, only to a savvy propagandist who knew how to pick and choose when to deploy each subtle facet of his family tree.

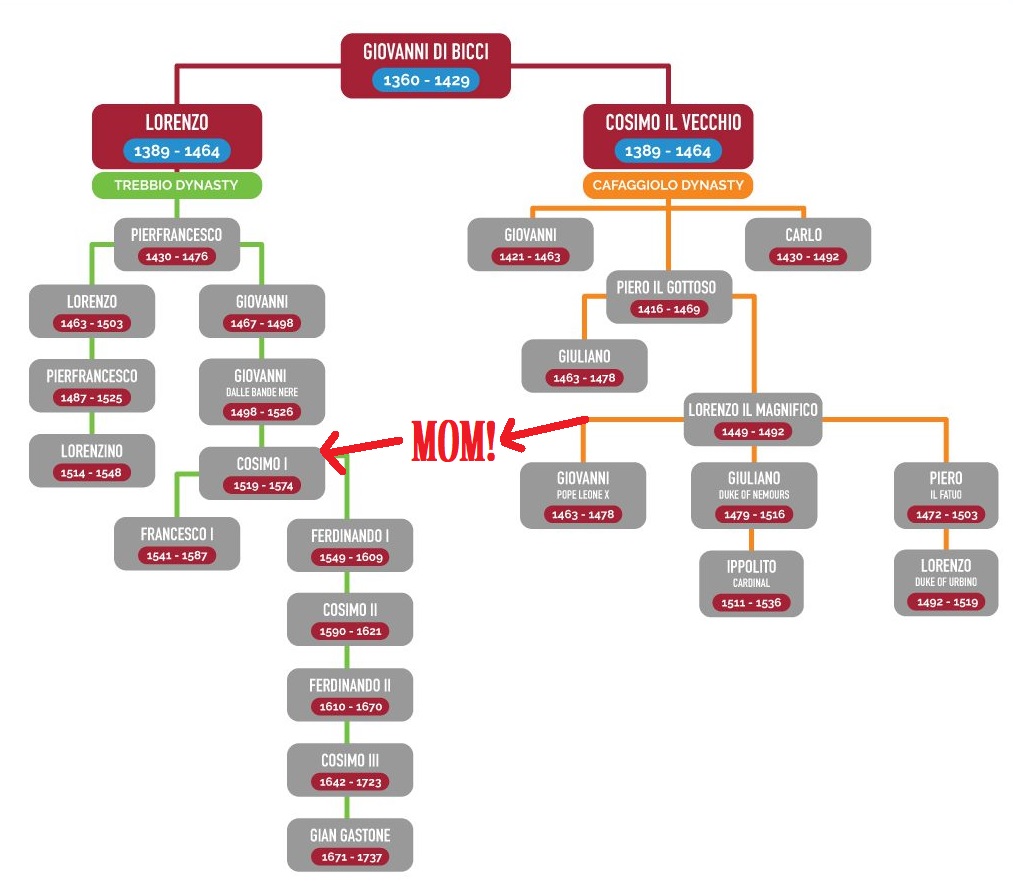

A second lesson I emphasized already: look up everybody’s mom! So many moments in history that make one say, “But why did X do Y?” or “Why did so-and-so suddenly show up?” are answered when you remember the nineteenth-century usually didn’t even bother to include daughters and moms on family trees unless they were royals. Take the example of what textbooks make always present as that weird branch family of Medici that seems to show up out of nowhere as fifth-cousins to suddenly be the dukes and successors to Medici power in the 1530s. Why them? Answer: look up everybody’s mom! If you do the tree with only the dads of course it’s gibberish!

(Footnote: if some parts of this essay seem like oblique references to the Musk-Trump situation in America right now in Feb. 2025, I don’t intend “look up his Mom!” specifically for them, I don’t think their moms are key to decoding politics today, I just think “look up his Mom!” is good historical practice, effective at decoding lots of stuff lots of the time).

Finally, both of these stories show the lasting power of propaganda. Sixtus played his cards cunningly to veil his privileged origin when it fit his mythmaking, and that propaganda is still being repeated by serious scholars here more than 500 years later. Da Costa, in contrast, didn’t want to be seen as coming from rags, and the faux nobility he adopted means you still to this day have to dig deep through his noble-sounding name, noble-looking crest, and noble-seeming tomb to find clues to the man beneath, who easily could have left us more information about his real mom and dad but didn’t want to.

If we want to write better histories, tell better narratives, understand better the real ways paths to power work and intersect with privilege, when Rags to Riches is real and when it’s propaganda, we have to evaluate the careers of the powerful by asking the questions which cut through their mythmaking. How much did his parents own? Where were they from? Were there immigrants in his family, refugees–what kind? If his dad was in Occupation X, was he a laborer or a bigwig owner of the means of production? Who did his siblings and aunts and uncles marry? How did he get launched in his first career? Did he, like Sixtus, start with connections which shot him past the early decades of hard work, straight to the foot-in-the-door-of-power job, or did he work for it coequally with others, as da Costa did? And how much of his path to power came from the mom’s side, so often totally erased?

History gives us the toolkit for such questions, critical to the critical thinking side of what the humanities and social sciences are supposed to do. It works.

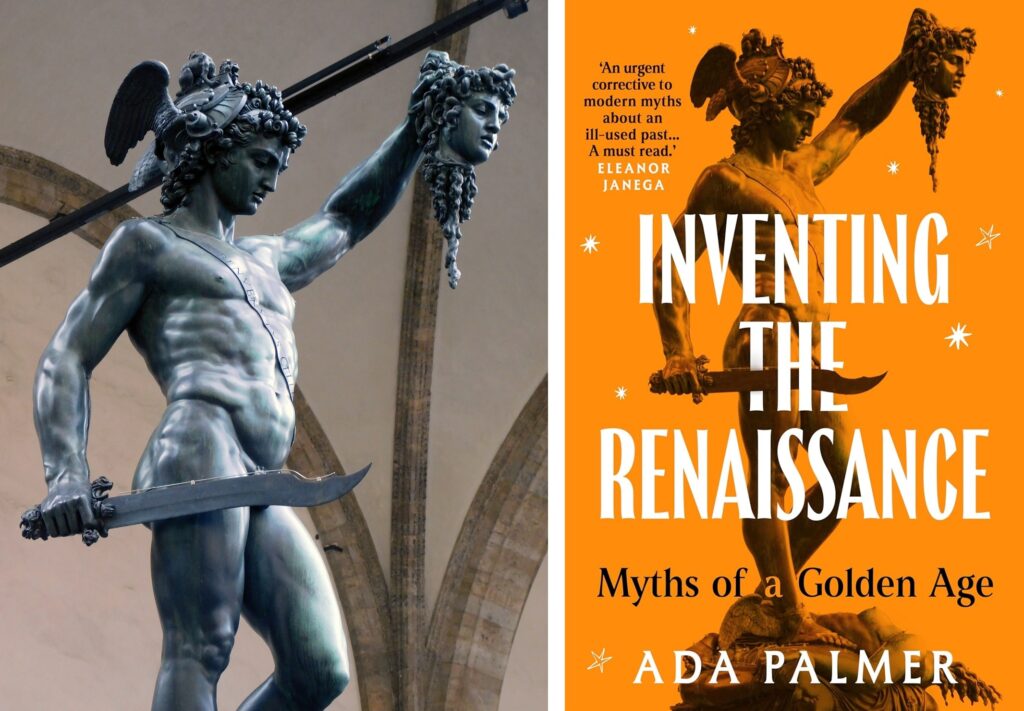

This post is part of my ramp-up to the release of Inventing the Renaissance, which discusses both men in their broader contexts, and the larger lens on power we get from the period. If you enjoyed this, there are more posts in the sequence to enjoy!

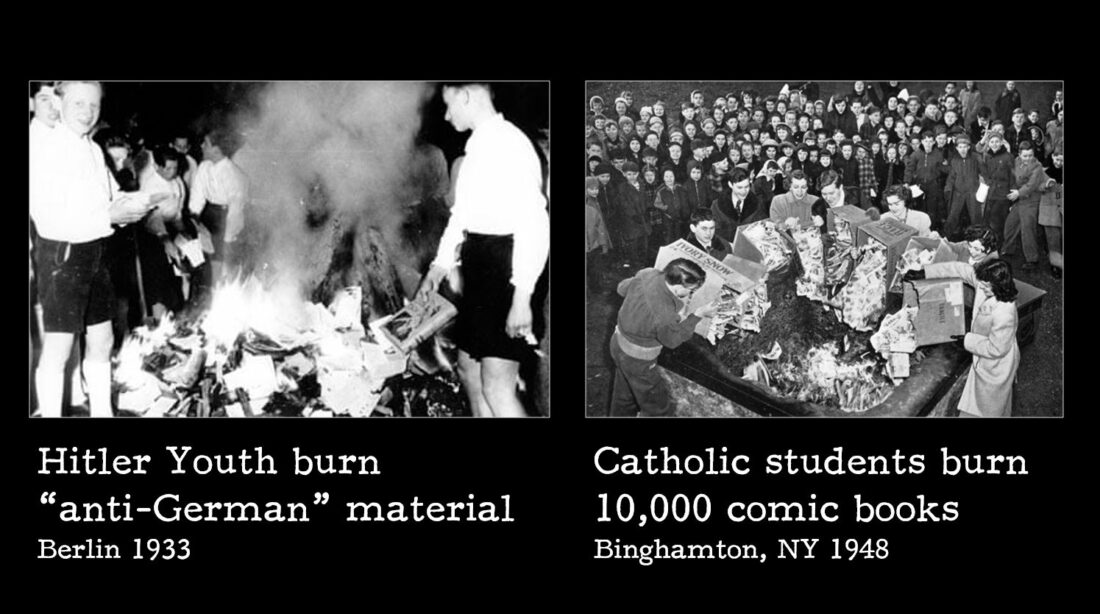

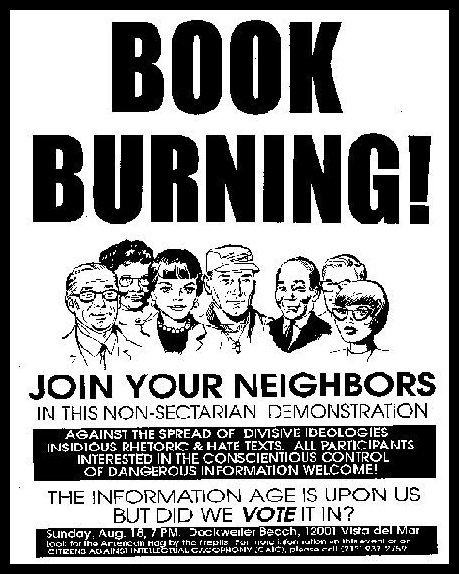

“Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”

“Was it a government action, or did they do it themselves because of pressure?”

No essay today, friends, but two announcements, of a fun project and sharing the spectacular list of panels I’m doing at Discon (Worldcon) in Washington DC in a few weeks! Worldcon is hybrid this year, so many of my panels will be available online!

No essay today, friends, but two announcements, of a fun project and sharing the spectacular list of panels I’m doing at Discon (Worldcon) in Washington DC in a few weeks! Worldcon is hybrid this year, so many of my panels will be available online!

Between Utopia and Dystopia:

Between Utopia and Dystopia: